TRAVEL

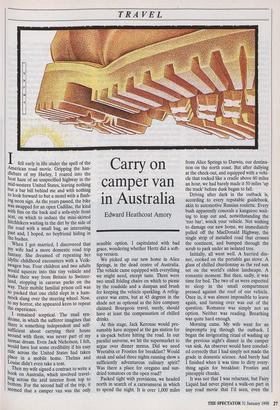

Carry on camper van in Australia

Edward Heathcoat Amory

Ifell early in life under the spell of the American road movie. Gripping the han- dlebars of my Harley, I roared into the heat haze of an unspecified highway in the mid-western United States, leaving nothing but a bar bill behind me and with nothing to look forward to but a motel with a flash- ing neon sign. As the years passed, the bike was swapped for an open Cadillac, the kind With fins on the back and a sofa-style front seat, on which to seduce the mini-skirted hitchhikers waiting in the dirt by the side of the road with a small bag, an interesting Past and, I hoped, no boyfriend hiding in the bushes.

When I got married, I discovered that my wife had a more domestic road trip fantasy. She dreamed of repeating her idyllic childhood encounters with a Volk- swagen bus. Four children and two adults would squeeze into this tiny vehicle and make their way from Britain to Switzer- land, stopping in caravan parks on the way. Their mobile familial prison cell was so packed that one child slept in a ham- mock slung over the steering wheel. Now, to my horror, she appeared keen to repeat the experience. I remained sceptical. The snail syn- drome, in which the sufferer imagines that there is something independent and self- sufficient about carrying their house around with them, was never part of my tarmac dream. Even Jack Nicholson, I felt, would have lost some credibility if his easy ride across the United States had taken Place in a mobile home. Thelma and Louise didn't even take a tent.

Then my wife signed a contract to write a book on Australia, which involved travel- ling across the arid interior from top to bottom. For the second half of the trip, it seemed that a camper van was the only sensible option. I capitulated with bad grace, wondering whether Hertz did a soft- top version.

We picked up our new home in Alice Springs, in the dead centre of Australia. The vehicle came equipped with everything we might need, except taste. There were two small folding chairs on which to picnic by the roadside and a dustpan and brush for keeping the vehicle sparkling. A refrig- erator was extra, but at 45 degrees in the shade not as optional as the hire company claimed. Bourgeois travel, surely, should have at least the compensation of chilled drinks.

At this stage, Jack Kerouac would pre- sumably have stopped at the gas station for a six-pack before hitting the road. In our parallel universe, we hit the supermarket to argue over dinner menus. Did we need Weetabix or Frosties for breakfast? Would steak and salad three nights running show a sufficiently adventurous culinary spirit? Was there a place for oregano and sun- dried tomatoes on the open road?

Packed tight with provisions, we headed north in search of a. caravanserai in which to spend the night. It is over 1,000 miles from Alice Springs to Darwin, our destina- tion on the north coast. But after dallying at the check-out, and equipped with a vehi- cle that rocked like a cradle above 60 miles an hour, we had barely made it 50 miles `up the track' before dusk began to fall.

Driving after dark in the outback is, according to every reputable guidebook, akin to automotive Russian roulette. Every bush apparently conceals a kangaroo wait- ing to leap out and, notwithstanding the `roo bar', wreck your vehicle. Not wishing to damage our new home, we inunediately pulled off the MacDonald Highway, the single strip of metalled road that crosses the continent, and bumped through the scrub to park under an isolated tree.

Initially, all went well. A hurried din- ner, cooked on the portable gas stove. A glass of chilled chardonnay as the red sun set on the world's oldest landscape. A romantic moment. But then, sadly, it was time for bed. The two of us were expected to sleep in the small compartment pressed against the roof of our vehicle. Once in, it was almost impossible to leave again, and turning over was out of the question. Romance was simply not an option. Neither was reading. Breathing was quite hard enough.

Morning came. My wife went for an impromptu jog through the outback. I began the invigorating ritual of washing up the previous night's dinner in the camper van sink. An observer would have conclud- ed correctly that I had simply not made the grade in domestic science. And barely had I finished when it was time to dirty every- thing again for breakfast: Frosties and pineapple chunks.

It was not that I was reluctant, but Fairy Liquid had never played a walk-on part in any road movie that I'd seen, even the

TRAVEL

French ones with Gerard Depardieu. In my favourite British moving vehicle picture, Withnail and I, Richard E. Grant had made a point of not doing the dishes.

Luckily, the baking wastes contained some isolated roadhouses. A few nights later, we checked into one which appar- ently boasted nearby thermal pools. The joys of civilisation beckoned: a meal cooked by others, no washing up, and a hot soak in natural surroundings to follow in the morning.

By the time we arrived, it was already dark. The piped music blaring from the speakers in the open-air restaurant was almost as unpalatable as the food. Our bedroom was so unpleasant that around midnight we slipped out for a tearful rec- onciliation with the camper van. In the morning it was time to visit the thermal pools. Sadly, several other visitors had the same idea. Had the water not been ther- mal, it could easily have been heated by the hundreds of sweaty bodies tightly packed in the steam, eddies of oil from their sun- screen floating on the few remaining patch- es of water.

Back in the camper van, I realised I was developing an almost unnatural affection for its compact charms. And then there were the collateral advantages: solitude, good cooking, wonderful surroundings, no need to assemble a tent. There seemed to be something rather compulsive about car- rying with you everything required for the maintenance of life. The snail syndrome had struck.

The Australian outback, unlike Africa, contains almost nothing, with the exception of a few snakes and spiders, that regards humans as fair game, so sleep comes rela- tively easily at night, once one is wedged into the minimalist sleeping area. A camper van also helps to avoid the princi- pal disadvantage of travelling in central Australia: other people with the same idea but, of course, less taste and charm than yourself.

We spent days in the semi-tropical rain- forest parks of the top end, afternoons with remote Aboriginal communities, evenings surrounded by the rocks of the Red Cen- tre, nights with kangaroos hopping around our campsite, and mornings dipping in deserted rock pools. In short, it was an extraordinary trip, and would only have been possible in a camper van.

This year we are going to Switzerland. I love the Alps, but have always had a problem with the smell of melted cheese that permeates every Swiss hotel and restaurant. Now there is a solution. We can take our home from home with us, complete with Notting Hill's finest sun- dried tomatoes and chardonnay. We might share a campsite with Margaret Beckett on the way. In my darkest mid- night thoughts, I even see a brightly coloured Volkswagen bus. My conversion to caravanning is complete.

Previous page

Previous page