Exhibitions 1

Alex Katz (Saatchi Gallery, till 12 April) Thomas &hiitte (Whitechapel Art Gallery, till 15 March)

Gigantic puzzle

Martin Gayford

There are tracts of American art, just as there are huge areas of America itself, that we over here seldom hear about. We know about Pop and Abstract Expressionism, just as we are thoroughly familiar with New York and LA, but we are much less aware of many of the bits north, south and in between. In artistic terms, one such forgot- ten territory is occupied by the veteran painter Alex Katz, whose work is currently 031 show at the Saatchi Gallery.

Katz is a figurative painter, but not a Pop artist exactly — though at times he looks Pop-ish — nor a realist, nor yet a photo- realist. This failure to conform to any recog- rased trend may explain why, I suspect, very few even among keen followers of art as much as knew his name before Charles Saatchi decided to organise this exhibition. It is a decision that deserves thanks, although in many ways Katz is a puzzling, not to say downright disconcerting artist. The unsettling thing is that one is not quite sure how to take his paintings. Katz, Who is 70 years old, has been painting figu- ratively since the Fifties (for much of the time, therefore, very much against the trend). Since the early Seventies, the peri- od covered by this show, he has also been Painting on a huge scale — some of the works in this show are 20 feet across. There's nothing unusual in that, of course, much post-war American art has inclined to giganticism. But the combination of heroic scale with the inconsequentiality of Katz subject matter and the blandness of his style is distinctly odd — so odd that it's interesting. He paints middle-class Americans in blankly ordinary contexts — a group of Pleasant youngsters sitting around on the beach, couples in clunkingly unhip leisure- 'wear walking in the woods, smartly dressed women in close-up. And he does all this in vast dimensions: a lady's head and half an umbrella cover 9Y2 feet by 12, half a woman's head and a section of hat, 91/2 by 4. These two pictures, particularly the lat- ter, have a great deal of pizazz and visual Punch. They hold your attention all right. But what do they mean? To paint a face this size — as big, as David Sylvester points out in the catalogue, as the head of Christ in a Byzantine dome — implies some large significance in the subject. But there doesn't seem to be any.

The way they are painted is puzzling too. The drawing is simplified, and verging on naive — eyes, for example, tend to come out too big, as in some of the Roman mummy portraits on show at the British Museum last year. There is a touch of mag- azine illustration about them, or the kind of painting that used to be done on adver- tisement hoardings – which is why Katz looks a little like the Pop art of Roy Licht- enstein or James Rosenquist. The colours are bright, or cheerily pastel.

A tempting explanation is that Katz is being ironic — poking fun at his bland, bourgeois world. But I think there's less irony here than appears to meet the eye. He himself talks about making 'something real for his time, where he lives'. And after all, America can strike you as rather like a Katz: huge, inclined to magnify trivia to vast proportions, rather bland, a little naive, fundamentally nice, with a lot of pizazz and punch.

Another painter whom he slightly resem- bles is Edward Hopper — often the refer- ence point for American figurative painters. They both catch that hard, clear American light, so unlike European sun- shine. But Hopper's figures are bleakly lonely and isolated; in Katz's paintings there is near emotional nullity: no drama, at most an occasional polite smile.

In addition to the figure paintings, Katz also paints landscapes — which many crit- ics, especially in America, tend to prefer. It is possible to see why. Katz is able to deploy the forceful simplifications and overall patterning of American abstraction while still clearly depicting trees, blossom and rippling water. The results are thor- oughly in the American grain and easier to enjoy (although with a moose he goes too far and produces something that looks like The Monarch of the Glen meets Walt Disney).

Personally, I thought the pictures of peo- ple odder and more interesting. Only a few of those, however, are really successful — all pictures of women's heads, 'The Blue Umbrella', 'The Red Band' and 'The Red Coat' — and apparently all of the same woman. In those, moreover, there might be an understated emotional undercurrent: erotic obsession. But the whole exhibition is worth seeing, and makes you want to see some more of those unpublicised American painters. The name of the late Fairfield Porter, for example, is always coming up in discussions of American figurative paint- ing, but his work remains virtually unexhib- ited in this country.

Thomas Schiitte, whose work is on show at the Whitechapel Art Gallery, resembles Katz in being little known in this country, and hard to know how to take — though not in most other ways. Now in his forties, Schfitte is part of the middle generation of German artists. His work has taken a bewildering variety of different forms — architectural models, installations, puppets, watercolour sketches of flowers, fruit and this and that — but the most immediately striking are the large-scale sculptures he calls 'Grosse Geister' or 'Big Spirits'.

These are aluminium giants, 21/2 metres high which, far from being demigods, resemble punctured Michelin Men, or robots that have started to melt in the sun. They are at once absurd, mock-threatening in the manner of fairground figures, and touching like the Tin Man in The Wizard of Oz. What they stand for is hard to say: deflating ideologies and exhausted beliefs — Marxism for instance — that continue to loom over us like the giants and witches in Goya? Schiltte doesn't say.

The counterparts of the 'Grosse Geister' — entitled 'United Enemies' — are tiny, equally grotesque, but more malign. The Enemies are nasty, irritable, bald old men,

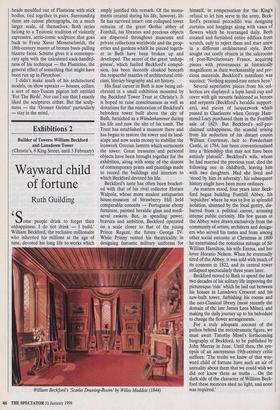

'The Blue Umbrella 2', 1972, by Alex Katz, on show at the Saatchi Gallery heads moulded out of Plasticine with stick bodies, tied together in pairs. Stu-rounding them are colour photographs, on a much larger scale, of themselves. Both series belong to a Teutonic tradition of violently expressive, serio-comic sculpture that goes back to Franz Xaver Messerschmidt, the 18th-century master of bronze busts pulling bizarre faces. Schiitte gives it a contempo- rary spin with the calculated cack-handed- ness of his technique — the Plasticine, the general effect of something that might have been run up in Playschool.

I didn't make much of his architectural models, on show upstairs — houses, cellars, a sort of neo-Tuscan pigeon loft entitled 'For The Birds'. Nor can I say that I exactly liked the sculptures either. But the sculp- tures — the 'Grosser Geister' particularly — stay in the mind.

Previous page

Previous page