Theatre

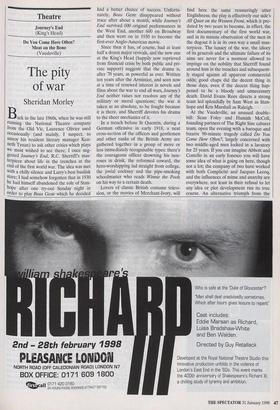

Journey's End (King's Head) Do You Come Here Often? Meat on the Bone (Vaudeville)

The pity of war

Sheridan Morley

Back in the late 1960s, when he was still fuming the National Theatre company from the Old Vic, Laurence Olivier used occasionally (and mainly, I suspect, to annoy his resident literary manager Ken- neth Tynan) to ask other critics which plays we most wished to see there; I once sug- gested Journey's End, R.C. Sherriffs mas- terpiece about life in the trenches at the end of the first world war. The idea was met With a chilly silence and Larry's best basilisk stare; I had somehow forgotten that in 1930 he had himself abandoned the role of Stan- hope after one try-out Sunday night in order to play Beau Geste which he decided had a better chance of success. Unfortu- nately, Beau Geste disappeared without trace after about a month, while Journey's End survived 600 original performances in the West End, another 600 on Broadway and then went on in 1930 to become the first-ever Anglo-American movie.

Since then it has, of course, had at least half a dozen major revivals, and the new one at the King's Head (happily now reprieved from financial crisis by both public and pri- vate support) suggests that the drama is, after 70 years, as powerful as ever. Written ten years after the Armistice, and seen now at a time of renewed interest in novels and films about the war to end all wars, Journey's End neither raises nor resolves any of the military or moral questions; the war is taken as an absolute, to be fought because it is there, and Sherriff devotes his drama to the sheer mechanics of it.

In a trench before St Quentin, during a German offensive in early 1918, a neat cross-section of the officers and gentlemen and other ranks of the British Army are gathered together in a group of more or less immediately recognisable types: there's the courageous officer drowning his neu- roses in drink, the reformed coward, the hero-worshipping lad straight from college, the jovial cockney and the pipe-smoking schoolmaster who reads Winnie the Pooh on his way to a certain death.

Lovers of classic British costume televi- sion, or the movies of Merchant-Ivory, will find here the same reassuringly utter Englishness; the play is effectively our side's All Quiet on the Western Front, which it pre- dated by two years to become, in effect, the first documentary of the first world war, and in its minute observation of the men in the dugout it is in its own way a small mas- terpiece. The lunacy of the war, the idiocy of its generals and the ultimate failure of its aims are never for a moment allowed to impinge on the nobility that Sherriff found around him in the trenches and subsequent- ly staged against all apparent commercial odds; good chaps did the decent thing in those days, even if the decent thing hap- pened to be a bloody and unnecessary death. David Evans Rees directs a strong team led splendidly by Sam West as Stan- hope and Kris Marshall as Raleigh.

At the Vaudeville, an unusual double- bill: Sean Foley and Hamish McColl, founding partners of The Right Size cabaret team, open the evening with a baroque and bizarre 90-minute tragedy called Do You Come Here Often?, largely concerned with two middle-aged men locked in a lavatory for 25 years. If you can imagine Abbott and Costello in an early Ionesco you will have some idea of what is going on here, though not a lot; the company of two have worked with both Compkite and Jacques Lecoq, and the influences of mime and anarchy are everywhere, not least in their refusal to let any idea or plot development run its true course. An alternative triumph from the Edinburgh Festival, Do You Come Here Often? must have made a lot more sense to a collegiate late-night audience than it does in prime time along the Strand.

For those of us who like our cabarets a little more musical, not to say coherent, the new Vaudeville policy of short-stay offbeat entertainments also has, later in the evening, the return of Kit and the Widow in Meat on the Bone, also prior to a nation- al tour. They are essentially all we have now in place of Flanders & Swann: Kit, coming to look increasingly like a jovial Erich von Stroheim, takes care of the words while the Widow, an enchanting pianist now bearing a distinct resemblance to Debbie Reynolds, partners him at the piano. The two men are deeply out of sorts with New Labour, Riverdance, Scottish dancing and Irish traditional folk song, and in early middle age they are acquiring an amiable distaste even for each other, let alone their loyal audiences. The new show has some brilliant new lyrics but seems somehow more of an effort to perform, as if the players had heard their own jokes once too often and are beginning to won- der whether a life in late-night cabaret is really all there is out there for a couple of hugely talented graduates. For our sake, I hope they decide that it is; we are still painfully short on their kind of waspish, topical satire and there is nothing quite like a couple of defrocked choirboys when it comes to really dishing the dirt.

Previous page

Previous page