The Glorious Resurrection of Our Lord

THEATRE

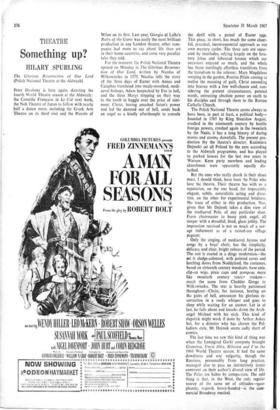

Something up?

HILARY SPURLING

(Polish National Theatre at the Aldwych) Peter Da ubeny is here again, directing the fourth World Theatre season at the Aldwych: the Comddie Francaise in Le Cid next week, the Nob Theatre of Japan to follow with nearly half a dozen more, including the Greek Arts Theatre on its third visit and the Piccolo of Milan on its first. Last year, Giorgio di Litllo's Rules of the Game was easily the most brilliant production in any London theatre; other com- panies had more to say about life than art in their home countries, and some very peculiar tales they told.

For the moment, the Polish National Theatre opened on Monday in The Glorious Resurrec- tion of Our Lord, written by Nicolas of Wilkowiecko in 1575. Nicolas tells the story of the three days of Easter with Annas and Caiaphas translated into mealy-mouthed, medi- aeval bishops, Adam henpecked by Eve in hell, and the three Marys stopping on their way to the tomb to haggle over the price of oint- ment. Christ, having smashed Satan's power and led the damned out of hell, sends back an angel as a kindly afterthought to console the devil with a parcel of Easter eggs. This piece, in short, has much the same cheer- ful, practical, inconsequential approach as our own mystery cycles. The three acts are separ- ated by interludes, relying largely on the lava- tory jokes and laboured hoaxes which our ancestors enjoyed so much, and the whole has those startlingly effortless transitions from the humdrum to the solemn: Mary Magdalene weeping in the garden, Pontius Pilate coming to realise the meaning of guilt, Christ ascending into heaven with a few well-chosen and, con- sidering the present circumstances, pointed words, entrusting absolute power on earth to his disciples and through them to the Roman Catholic Church.

The Polish National Theatre seems always to have been, in part at least, a political body— founded in 1765 by King Stanislaw August, crushed in the nineteenth century by hostile foreign powers, crushed again in the twentieth by the Nazis, it has a long history of daring moves and stormy downfalls. The present pro- duction (by the theatre's director, Kazimierz Dejmek) set all Poland by the ears according to the Aldwych programme, and has played to packed houses for the last two years in Warsaw. Keen party members and leading churchmen were apparently equally dis- turbed.

But the ones who really shook in their shoes must, I should think, have been the Poles who love the theatre. Their theatre has with us a reputation, on the one hand, for impeccably elegant, subtle, naturalistic acting and direc- tion, on the other for experimental boldness. No trace of either in this production. Nor, given that Mr Dejmek takes a dim view of the mediaeval Pole, of any particular slant. From choirmaster to bossy pink angel, all simper with a dreadful, fixed, glum jollity. The impression received is not so much of a sav- age indictment as of a rained-out village pageant.

Only the singing, of mediaeval hymns and songs by a boys' choir, has the simplicity, delicacy and clear, bright colours of the period. The rest is coated in a dingy modernism—the set is sludge-coloured, with pointed eaves and lurching doors from Noddyland, the costumes, based on sixteenth century woodcuts, have cute, clip-on wigs, pixie caps and pompons more like twentieth century tourist trinkets— much the same from Cheddar Gorge to Wilkowiecko. The text is heavily patronised throughout—Christ, for instance, beating on the gates of hell, announces his glorious re- surrection in a reedy whisper and goes to sleep while waiting for an answer. Let in at last, he falls about and knocks down the Arch- angel Michael with his stick. This kind of slapstick might work if done by Arthur Askey but, for a director who has chosen the Pal- ladium style, Mr Dejmek seems sadly short of comics.

The last time we saw this kind of thing was when the Leningrad Gorki company brought Grandma, Uncle Iliko, Hilarion and 1 tb the 1966 World Theatre season. It had the same dowdiness and coy vulgarity, though the Russians, presumably from long practice, managed also to pass an instinctively ironic comment on their author's dismal view of life. The Poles are babes by comparison. The odd thing is that, in the West, the only regular source of the same set of attitudes—syco- phantic, roguish, heavy-handed—is the com- mercial Broadway musical.

Previous page

Previous page