Oil and Scottish Waters

By DAVID MURRAY

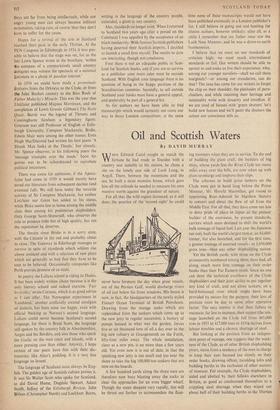

WIIEN Edward Caird sought to match the fortune he had made in Dundee with a country seat suitable to his station, he chose a site on the lonely east side of Loch Long, in Argyll. There, between the mountains and the sea, he built a stout mansion house, which gave him all the solitude he needed to measure his own massive worth against the grandeur of nature.

For all that the wild region favoured, as it still does, the practice of the 'second sight' he could never have foreseen the day when great vessels, out of the Persian Gulf, would discharge rivers of oil just below his front windows. His house is now, in fact, the headquarters of the newly styled Finnart Ocean Terminal of British Petroleum. Drawing from the storage tanks which are replenished from the tankers which come up to the new jetty in regular succession, a battery of pumps housed in what was the garden, forces five or six thousand tons of oil a day over to the big new refinery at Grangemouth on the Forth, fifty-four miles away. The whole installation, clean as a new pin, is no more than a few years old. Yet even now it is out of date, in that the spanking new jetty is too small and too near the shore to take the big 100,000-ton tankers that are now on the boards.

A few hundred yards along the shore men are therefore now busy blasting away the rocks to clear the approaches for an even bigger wharf. Though the water deepens very rapidly, this will be thrust out farther to accommodate the float- ing monsters when they are in service. To the end of building the giant craft, the builders of big ships, whose yards line the River Clyde not many miles away over the hills, are now taken up with plans to enlarge and improve their slips.

The schemes to build great tankers on the Clyde were put in hand long before the Prime Minister, Mr. Harold Macmillan, got round to appointing Rear-Admiral Sir Matthew Slattery to concert and direct the flow of oil from the Middle East. For all that, they have come too late to deny pride of place to Japan as the pioneer builder of the enormous, by present standards, carriers which seem destined to shift the world's bulk tonnage of liquid fuel. Last year the Japanese not only built the world's largest tanker, an 84,000- tonner, but also launched; and for the first time, a greater tonnage of assorted vessels—at 1,650,000 gross tons—than any other shipbuilding nation.

Yet the British yards, with those on the Clyde prominently numbered among them, have had, all along, much more firm tonnage on their order books than their Far Eastern rivals. Since no one can deny the technical excellence of the Clyde shipbuilders and their joint ability to put together any kind of craft, and not alone tankers, on a hard-bottomed river which might have been provided by nature for the purpose, their loss of position must be due to some other operative factor. The easy answer is that their failure to maintain, far less to increase, their output (the ton- nage launched Son. the Clyde fell from 485,000 tons in 1955 to 417,000 tons in 19564 derives from labour troubles and a chronic shortage of steel.

But looking at the position from an indepen- dent point of vantage, one suggests that the weak- ness of the Clyde, as of other British shipbuilding rivers, stems from a tendency of the men in charge to keep their eyes focused too closely on their order books, drawing offices, moulding lofts and building berths to the exclusion of other matters of moment. For example, the Clyde shipbuilders, aided and abetted by their fellows elsewhere in Britain, as good as condemned themselves to a crippling steel shortage when they wiped out about half of their building berths in the Thirties in aid of,pruning away surplus capacity. Taking the direct'cue, the steelmakers promptly scrapped plate mills right and left, to such an extent that, until quite recently, the tonnage of plates rolled in Scotland, in particular, was no greater than in the early Twenties.

When it became evident that all the technical trends favoured the usage of plates, not only in the building of ships (a dry-cargo vessel is now about four-fifths plates, and a tanker about six- sevenths) but also in general steel construction, the shipbuilders remained, like Achilles, sulking in their tents. True enough they came out now and again to voice their displeasure about the steel-plate shortage to a broader audience, especially at the launching ceremonies. But they failed to put the point forcibly and succinctly enough in the quarters where it might have had some stirring effect. Though a crippling lack of plates has remained for twenty long years, at the root of their inability to match demand with pro- duction and thus to distribute rewards sufficient to mollify, if not completely satisfy, their workers, some prominent Clyde shipbuilders actually en- couraged, albeit indirectly, the hedging steel- makers to 'Ca' canny' with plans to expand plate production materially. That was when, by setting normal sinkings and scrappings against the esti- mated needs of the• world for shipping, they worked out that the post-war boom would last only a few years. After that, they argued, the world's capacity to build ships would far sur- pass its requirements.

It appeared also to escape them that, apart altogether from the increasing traffic on the seas, in large part due ,to wars and fears of them, the new technical trends in ship design—as opposed to those in ship construction—would force owners to keep on buying new craft. Their analyses, in short, have always tended to be too static and to take little account of the fructifying nature, as regards business, of both war threats and of technical changes. Today, having seen that the world demand for shipping is again very buoyant, with no apparent near end of it, after the hesitancy of a year or so ago the Clyde shipbuilders are now disposed to take a longer and a closer view of the future and to brace themselves accordingly. Now that the Government itself is at pains to put an end to the steel plate shortage which has been the bane of Clyde shipbuilding for twenty years, it would seem that the strictly material basis of shipbuilding will be assured in a few years' time when new 'rolling mills are in com- mission. In that event, the technical abilities of those who build ships so well on the Clyde may be allowed to flower as never properly for years.

In the meantime, it might be a good idea if they built a country retreat away up in lonely Loch Long, where British Petroleum is preparing to receive big 100,000-ton tankers. There they might be in a better position to assess the factors which have, in fact, conditioned the design of and demand for ships than amid the noise and bustle of the yards. Having a good position, good men and any amount of skill in running up vessels and putting engines into them, the Clyde ship- builders need, above all else, a measure of that quality which distinguishes those who live in the lonely places. That 'second sight' is no more than the ability to peer into the future and cast up its probable fruits.

Previous page

Previous page