MISMANAGING 'GILT-EDGED'

By NICHOLAS DAVENPORT IT is not the state of the economy which is responsible for the present \ Demoralisation in the gilt-edged

market. There has been no new rise in prices since January. The wage settlement in the engineering .industry allows the possibility of an increase in productivity to offset the rise in wages. The sizeable reduction in defence spend- ing and the release of manpower from the Ser- vices are the most important contribution which any postwar government has made to the casing of pressure on prices and wages. No, the blame must be put on the Treasury and Bank of England `experts' who manage (or mismanage) the gilt- edged market.

* * *

No doubt they will find scapegoats. They will point to the momentous decision of Lloyds to allow their underwriters to hold half their re- quired deposits in equity shares. This has, indeed, led to a steady trickle of private selling of Govern- ment stocks for which there are no ready buyers —until the Government broker walks into the market as he did last Friday. Of course, a change in investment policy on the part of the very con- servative council of Lloyds must have a big influence on private investors and trustees—as did the decision of the Church of England a few years ago to put £40 million of the Church funds into equity shares. Investment escapism is highly infectious. Jobbers in the gilt-edged market report a steady stream of small private selling.

* * *

Of course, Government bonds are hopeless investments for pension funds or anyone else if the value of money is to be blown away by a third world war. But is any other form of invest- ment going to be worth much after the H-bombs begin to fall? The choice between Government bonds and equities does not rest upon the prospect of another war inflation but upon that of a creep- ing inflation brought about by the bi-partisan policy of full employment. Certainly, creeping inflation is enough to make the average private investor prefer equities to bonds, but insurance companies have got to hold a proportion of their funds in redeemable Government stocks, matched against the average term of their liabilities, and if the Government budgets for a heavy surplus, as it is bound to do when a creeping inflation is threatened, the insurance companies' annual net demand for gilt-edged securities should, on balance, exceed the annual supply—that is, if the Treasury knows how to manage its business properly. But does it?

* * *

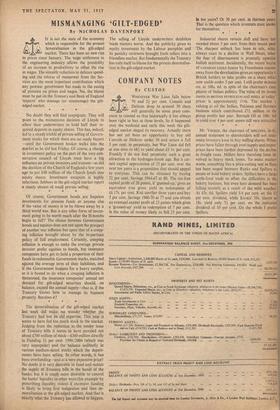

The demoralisation of the gilt-edged market last week did make me wonder whether the Treasury had lost its old expertise. This year it seems to have fed too much stock to the market. Judging from the reduction, in the tender issue of Treasury bills it seems to have pumped out about £700 million of stock—£300 million directly in Funding 3-k per cent. 1999/2004 (which was very unpopular) and the balance indirectly in various medium-dated stocks which the depart- ments have been selling. In other words, it has been overfunding—and at a very expensive pried! No doubt it is very desirable to fund and reduce the supply bf Treasury bills in the hands of the banks; but it is mucl) more desirable to control the banks' liquidity in other ways (for example by prescribing liquidity ratios) if excessive funding is likely to bring first indigestion and then de- moralisation in the gilt-edged market. And that is exactly what the Treasury has allowed to happen. The selling of Lloyds underwriters doubtless made matters worse. And the publicity given to equity investment by the Labour pamphlet and its panicky reviewers brought fresh sellers into a friendless market. But fundamentally the Treasury has only itself to blame for the present demoralisa- tion in the gilt-edged market.

Previous page

Previous page