Exhibitions 1

Addressing the Century (Hayward Gallery, till 11 January)

Just looking

Martin Gayford

It is only shallow people,' as Oscar Wilde noted, 'who do not judge by appear- ances.' Ergo, for serious, arty folk at least clothes matter. That is certainly the con- tention of Addressing the Century, an exhi- bition that presents clothes as art and art as clothes — not exactly the same thing, as will appear below. Apart from the title, one of those ghastly, pretentious puns to which contemporary academics are prone, it is an interesting and brilliantly presented show.

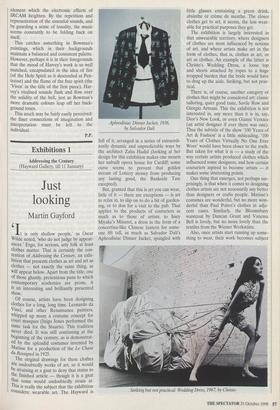

Of course, artists have been designing clothes for a long, long time. Leonardo da Vinci, and other Renaissance painters, whipped up many a costume concept for court masques (Inigo Jones performed the same task for the Stuarts). This tradition never died. It was still continuing at the beginning of the century, as is demonstrat- ed by the splendid costumes invented by Matisse for a production of the Le Chant du Rossignol in 1925. The original drawings for these clothes are undoubtedly works of art, so it would be straining at a gnat to deny that status to the finished article — though it is a gnat that some would undoubtedly strain at. This is really the subject that the exhibition considers: wearable art. The Hayward is Aphrodisiac Dinner Jacket, 1936, by Salvador Dali full of it, arranged in a series of extraordi- narily dynamic and unpredictable ways by the architect Zaha Hadid (looking at her design for this exhibition makes one mourn her unbuilt opera house for Cardiff; some curse seems to prevent that golden stream of Lottery money from producing any lasting good, the Bankside Tate excepted).

But, granted that this is art you can wear, little of it — there are exceptions — is art to relax in, to slip on to do a bit of garden- ing, or to don for a visit to the pub. That applies to the products of couturiers as much as to those of artists: to Issey Miyake's Minaret, a dress in the form of a concertina-like Chinese lantern for some- one 8ft tall, as much as Salvador Dali's Aphrodisiac Dinner Jacket, spangled with little glasses containing a green drink, absinthe or crème de menthe. The closer clothes get to art, it seems, the less wear- able for practical purposes they get.

The exhibition is largely interested in that unwearable territory, where designers of clothes are most influenced by notions of art, and where artists make art in the form of clothes, that is, clothes as art, or art as clothes. An example of the latter is Christo's Wedding Dress, a loose top and shorts attached by ropes to a huge wrapped burden that the bride would have to drag up the aisle. Striking, but not prac- tical.

There is, of course, another category of clothes that might be considered art: classic tailoring, quiet good taste, Savile Row and Giorgio Armani. This the exhibition is not interested in, any more than it is in, say, Dior's New Look, or even Gianni Versace (an artist designer if ever there was one). Thus the subtitle of the show '100 Years of Art & Fashion' is a little miMeading. '100 Years of Clothes Virtually No One Ever Wore' would have been closer to the truth. But taken for what it is — a study of the way certain artists produced clothes which influenced some designers, and how certain couturiers aspired to become artists — it makes some interesting points.

One thing that emerges, not perhaps sur- prisingly, is that when it comes to designing clothes artists are not necessarily any better than designers or crafts people. Matisse's costumes are wonderful, but no more won- derful than Paul Poiret's clothes in adja- cent cases. Similarly, the Bloomsbury waistcoat by Duncan Grant and Vanessa Bell is lovely, but no more lovely than the textiles from the Wiener Werkstatte.

Also, once artists start running up some- thing to wear, their work becomes subject Striking but not practical: Wedding Dress, 1967, by Christo to the laws of fashion (even more than art is). That is, what looks great this year will look thoroughly passé by and by. Even the rudest of shocks can wear off. This is illus- trated by a series of mannequins dressed by various Surrealists in 1938. Some of these get-ups, admittedly, are still quite startling. Any woman wearing Andre Mas- son's rig — nothing but a birdcage on the head, two dead birds in the armpits, and a small oval mirror, decorated with glass eye-balls and strategically-placed — would still turn a few heads in the street. Marcel Duchamp's costume — man's jacket, waistcoat, shirt and hat, and no trousers must have seemed equally outré at the time. These days, I submit, it would raise few eyebrows. (The Surrealist clothes by Elsa Schiaparelli, on the other hand, still look great, especially the monkey-fur shoes and jacket with vegetable buttons, though admittedly neither is exactly everyday wear.) Fashion has caught up with Duchamp perhaps it will with Masson in a while. Sim- ilarly, Gilbert and George must have looked quite extraordinary in the 1970s, when it was normal to wear corduroy flares, and lots of hair on your face. Now, they look fairly normal, because the world has come to look more like them. They have probably had more direct effect on the way people dress than any other artist in this exhibition. There are racks of Gilbert and George suits in smart men's outfitters the world over.

G&G make another point. As often hap- pens, they upstage every other exhibit — in this case because they appear in person, or rather on film, dancing to the song 'Bend It' in a manner stiff, jerky, and strangely touching, like shop window dummies come to life. Rivals such as Joseph Beuys, on the other hand, are represented only by special felt and paper suits on hangers, which brings out a fundamental problem about the whole enterprise. All right, clothes are, or can be, art. But they are only fully-func- tioning art under special circumstances, i.e. when someone is wearing them, just as fountains are only truly effective when the water is switched on, stage sets while the performance is under way, and so forth. That is why fashion houses employ models, rather than displaying their clothes on hangers.

This poses problems for museums of cos- tumes and exhibitions such as this. You could scarcely have several hundred live models hanging around in the Hayward all day, wearing birdcages on their heads (striking and popular though such a show might be). On the other hand, there is something inert and incomplete about clothes without people in them. Still, in this case the intrinsic dullness of uninhabited costumes is offset by the splendid presenta- tion by Zaha Hadid. The result is an unusual exhibition, especially intriguing to all those who believe that you are what you wear.

Previous page

Previous page