Exhibitions 2

Bathers (New York Studio School, till 14 November)

Shocking practices

Roger Kimball

Perhaps the most subversive art institu- tion in New York City these days is located at 8 West 8th Street in the building that once housed Gertrude Vanderbilt Whit- ney's art studios and was the original site of the Whitney Museum of American Art. I mean the New York Studio School. This small art school has been around in one form or another since 1964. But its truly transgressive character really emerged only after 1988 when the English painter Gra- ham Nickson became dean and trans- formed the curriculum. Emerson once said that 'an institution is the lengthened shad- ow of one man'. That is certainly true at the Studio School. For since Graham Nick- son came on board, the school has regularly engaged in numerous activities certain to outrage entrenched interests in the art world even as it has challenged the reigning orthodoxies of what has become in many quarters conventional artistic wisdom.

The list of shocking practices one finds at the Studio School is long. For one thing, Graham Nickson has seen to it that draw- ing — you know, mastery of the skill need- ed to wield pencil, chalk, or charcoal effectively — occupies a central place in the school's teaching. For another, students are encouraged to look for their inspiration not to the recent crop of celebrity artists from SoHo or TriBeCa or Cork Street but to the riches of art history back to the Renaissance and beyond. Then, too, words like 'traditional' and 'beautiful' are taken not as terms of ironic denigration but as terms of praise at the Studio School. In fla- grant disregard of every current artistic cliché, students are taught to regard the Western artistic tradition as an immense enabling resource rather than as an impediment to the expression of their cre- ativity.

As part of this heterodox programme, the Studio School regularly mounts small exhibitions of pictures by masters old and new. The intention behind the exhibitions is partly pedagogical. They are meant to serve as models and sources of technical guidance for the students. They are also meant to be objects of aesthetic delectation in their own right. How successful they can be in this second ambition is shown by the current exhibition of some 40 small works devoted to the venerable theme of bathers.

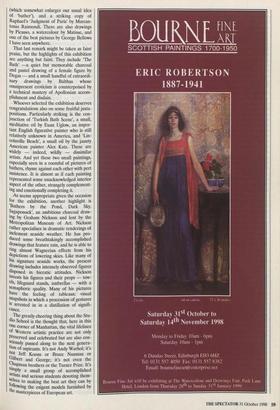

The exhibition, culled from several pub- lic and private collections, was organised to honour Graham Nickson, who is celebrat- ing his tenth year as dean and whose own work often depicts figures on a beach. It includes lithographs by Cezanne, Boucher, Bonnard, Delacroix, and Pissarro, a pen and ink 'Baptism of Christ' by Tiepolo `Bathers by the Pond, Dark Sky, Sagaponack, 1981, by Graham Nickson, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, gift of Dr and Mrs Robert E Carroll (which somewhat enlarges our usual idea of 'bather), and a striking copy of Raphael's 'Judgment of Paris' by Marcan- tonio Raimondi. There are also drawings by Picasso, a watercolour by Matisse, and one of the best pictures by George Bellows I have seen anywhere.

That last remark might be taken as faint praise, but the highlights of this exhibition are anything but faint. They include 'The Bath' —a quiet but memorable charcoal and pastel drawing of a female figure by Degas — and a small handful of extraordi- nary drawings by Balthus whose omnipresent eroticism is counterpoised by a technical mastery of Apollonian accom- plishment and disdain.

Whoever selected the exhibition deserves congratulations also on some fruitful juxta- positions. Particularly striking is the con- junction of 'Turkish Bath Scene', a small, meditative oil by Euan Uglow, an impor- tant English figurative painter who is still relatively unknown in America, and lin- eolnville Beach', a small oil by the jaunty American painter Alex Katz. These are widely — indeed, wildly — dissimilar artists. And yet these two small paintings, especially seen in a roomful of pictures of bathers, rhyme against each other with pert insistence. It is almost as if each painting represented some unacknowledged interior aspect of the other, strangely complement- ing and emotionally completing it.

As seems appropriate given the occasion for the exhibition, another highlight is `Bathers by the Pond, Dark Sky, Sagaponack', an ambitious charcoal draw- ing by Graham Nickson and lent by the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Nickson rather specialises in dramatic renderings of inclement seaside weather. He has pro- duced some breathtakingly accomplished drawings that feature rain, and he is able to ring almost Wagnerian effects from his depictions of lowering skies. Like many of his signature seaside works, the present drawing includes intensely observed figures disposed in hieratic attitudes. Nickson invests his figures and their props — tow- els, lifeguard stands, umbrellas — with a semaphoric quality. Many of his pictures have the feeling of tableaux: visual snapshots in which a procession of gestures is arrested in in a distillation of signifi- cance.

The greatly cheering thing about the Stu- dio School is the thought that, here in this one corner of Manhattan, the vital lifelines of Western artistic practice are not only preserved and celebrated but are also con- s', iensly passed along to the next genera- tion of aspirants. It's not Andy Warhol; it's not Jeff Koons or Bruce Nauman or Gilbert and George; it's not even the Chapman brothers or the Turner Prize. It's sintply a small group of accomplished artists and serious students devoting them- selves to making the best art they can by following the exigent models furnished by the masterpieces of European art.

Previous page

Previous page