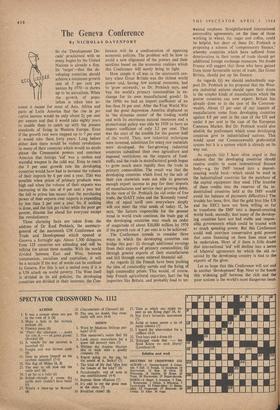

The Geneva Conference

By NICHOLAS

DAVENPORT

So the 'Development De- cade' proclaimed with so many bugles by the United Nations is already a flop. Its `target'-that the de- veloping countries should achieve a minimum growth rate of 5 per cent per annum by 1970-is shown up to be unrealistic. When the growth of popu- lation is taken into ac- count it meant for most of Asia, Africa and parts of Latin America that the rise in per capita income would be only about 21 per cent per annum and that it would take eighty years to enable them to catch up with the present standards of living in Western Europe. Even if the growth rate were stepped up to 7 per cent it would take them forty years. Long before either date there would be violent revolutions in many of their countries which would no doubt please the Communist powers and convince America that foreign 'aid' was a useless and wasteful weapon in the cold war. Even to reach the 5 per cent growth rate the developing countries would have had to increase the volume of their imports by 6 per cent a year. This was possible when prices of primary products were high and when the volume of their exports was increasing at the rate of 4 per cent a year but the fall in prices has meant that the purchasing power of their exports over imports is expanding by less than 2 per cent a year. So, if nothing is done, and the rich get richer while the poor get poorer, disaster lies ahead for everyone except the revolutionary.

These alarming facts are taken from the address of Dr Raul Prebisch, the secretary- general of the mammoth UN Conference on Trade and Development which opened at Geneva a fortnight ago. About 1,500 delegates from 123 countries are attending and will be talking for about three months. With the world divided between East and West, between communism, socialism and capitalism, it will be a miracle if the war of words can be confined to Geneva. For this is not a united even if it is a UN attack on world poverty. The West itself is divided in its aid policies; the developing countries are divided in their interests; the Con- ference will be a confrontation of opposing economic policies. The problem will be how to avoid a new alignment of the powers and their satellites based on the economic realities which this Conference will surely bring to light.

How simple it all was in the nineteenth cen- tury when Great Britain was the richest world power and, having few natural resources, had to 'grow outwards,' as Dr. Prebisch says, and buy the world's primary commodities in ex- change for its own manufactured goods! In the 1890s we had an import coefficient of no less than 36 per cent. After the First World War and the great depression America displaced us as 'the dynamic centre' of the trading world and with its enormous natural resources and a protectionist policy was able by 1939 to have an import coefficient of only 3.2 per cent. That was the start of the trouble for the poorer half of the world. Then, new industrial techniques were invented, substitutes for many raw materials were developed, the fast-growing industrial countries subsidised their own agriculture and imposed restrictions on the imports of food- stuffs, and the trade in manufactured goods began to grow much more rapidly than the trade in primary commodities. The result was that the developing countries which lived by the sale of their raw materials were not able to generate enough export income to pay for their imports of manufactures and service their growing debts. In the view of Dr. Prebisch the old order of free trade, the GATT rules and the 'Kennedy round' idea of equal tariff cuts everywhere simply will not meet the vital needs of today. If, he says, 'the factors responsible for the present trend in world trade continue, the trade gap of the developing countries may reach an order of magnitude of about $20,000 million by 1970 if the growth rate of 5 per cent is to be achieved.'

The Conference intends to consider three ways in which the developing countries can bridge this gap: (i) through additional earnings from their exports of primary commodities; (ii) through greater exports of their manufactures and (iii) through more external financial aid.

As regards (i) the French have been pushing the idea of commodity cartels and the fixing of high commodity prices. This would, of course, help French agricultural exporters, hurt the big importers like Britain, and probably lead to un-

wanted surpluses. Straightforward international commodity agreements, on the lines of those working in wheat, tin, sugar and coffee, could be helpful, but short of these Dr. Prebisch is proposing a scheme of 'compensatory finance,' whereby countries which have suffered from deterioration in their terms of trade should get additional foreign exchange resources. No doubt France will suggest that those who have gained from more favourable terms of trade, like Great Britain, should put up the finance.

As regards (ii) we should undoubtedly sup- port Dr. Prebisch in his proposal that the West- ern industrial nations should open their doors tc the simpler kinds of manufactures which the poorer countries can now export. Britain has already done so in the case of the Common- wealth. About 13 per cent of our imports of manufactures come from developing countries against 8.8 per cent in the case of the US and under 4 per cent in the case of the European Common Market. But Dr. Prebisoh would also abolish the preferences which some developing countries give to industrialised nations. This would upset our Commonwealth preferential system but it is a system which is already on its way out.

As regards (iii) I have often urged in this column that the developing countries should receive credits in some international finance body-e.g. the IMF turned into a deposit- creating world bank-which could be used in the industrialised countries for the purchase of the capital equipment they need. (The transfer of these credits into the reserves of the in- dustrialised countries held at the IMF would avoid the balance of payments difficulties.) The trouble has been, first, that the gold bloc (the US and the EEC) have not been willing so far to transform the IMF into a deposit-creating world bank, secondly, that many of the develop- ing countries have not had stable and respon- sible governments which could be trusted with So much spending power. But this Conference could well convince conservative gold powers that some financing on these lines must now be undertaken. Short of it there is little doubt that international 'aid' will decline into a series of bilateral agreements by which the aid re- ceived by the developing country is tied to the exports of the giver.

Let us hope that this Conference will not end in another 'development' flop. Next to the bomb this widening gulf between the rich and the poor nations is the world's most dangerous issue.

Previous page

Previous page