The road to Muggers' Alley

Roy Kerridge

When the Mayor of Lambeth, in the early Fifties, publicly welcomed West Indians and gave a banquet for them in the Town Hall, he apparently never thought of asking them where they were going to sleep that night. 'I waited and waited on that railway platform,' a Jamaican housewife told me, describing her arrival in Britain in 1953, 'and no one came from the govern- ment to tell me where to live.'

We are accustomed to thinking of West Indians as brash, capable people, well able to take care of themselves. Some give that impression, but there is another side to them, that of helpless uprooted peasants who look to authority for guidance. If some of their descendants are now criminals, as police statistics suggest, it. shows the sort of guidance they have received. Councils would not house them, no 'refugee camps' were set up, and working-class landladies were quite unprepared. Some even scream- ed at the sudden appearance of a black man.

Educated opinion in Britain at that time tended to he communist in tone, and work- ing men all over the world were thought to be brothers. Race prejudice was vaguely supposed to be the prerogative of middle- class snobs somewhere in Surrey, who didn't want to play golf with Jews. No one prepared the British working man and the West Indian for one another, and the shock was mutual. The white working class of the Fifties were held together by a good- humoured feeling that their way of life was the only one there was, and they were in- credulous at the sudden appearance of `darkies' in their midst. They would not let rooms to them, and would not believe West Indian dialect was English, which its speakers had always imagined it to be. Many assumed that the newcomers were from jungles or from the west of India. Membership of the British Empire was at that time very important for West Indian self-esteem, but to the white British work- ing man it only meant jokes about Colonel Blimp and the public school spirit. Walking the streets with suitcases, the pioneer West Indians, mostly men who would send for their families later, were forced to take room and refuge in Little Africa.

Nowadays we think of Africans in England as eminently respectable law students, but in the late Forties a different breed appeared. These were the so-called 'waterfront boys' who for some years had lived as mudlarks around West African docks. Originally they had run away from

overbearing parents or guardians, and lived by their wits hopping around the quaysides and helping or hindering the older dock- workers. From returning seamen and memories of Empire Day parades they pick- ed up a highly romantic picture of Britain, and sat looking out to sea and yearning for `the other side'.

Some signed on as sailors as soon as they were old enough and jumped ship in Lon- don or Liverpool, a few paid their way, and many stowed away. Successful stowawaYs at that time could become lawful British citizens after serving a short prison sentence for attempted fare-dodging. Ships could not turn' back, and the stowaways would reveal themselves when out at sea.

Frankie McKay of Freetown, Sierra Leone, told me of a terrifying experience he underwent while stowing away with several others in the hold of a cargo vessel bound for Britain. While stopping at another port, the hatch above their heads opened and several tons of loose peanuts poured down on top of them, burying them alive. Two boys died, but Frank survived to serve his sentence, and found himself adrift and pen' niless in an uncaring city at the age of 16. A night watchman in the East End let him sit by the fire each night until he found a place to stay. From this shaky start in life, Frank has become a master printer as well as a musician who played with Nat King Cole. Waterfront boys lived a curious `underground' life in our cities, unrecognis- ed by the authorities and by educated pea' ple, and feared by the respectable working class. Petty 'criminals, however, were. delighted to find such lively company, and often became the only Englishmen the new arrivals knew. Ladies of the town were hap- py to find gallants who lacked the sadism of the Maltese gangsters who at that time con- trolled their earnings. Today, many former waterfront boys are successful businessmen and skilled craftsmen, but in the process of their growing up a 'black underworld' has been created, which many of the later- coming West Indians have been pressed in- to, almost inadvertently. Successful West Africans often bought decrepit houses for a few hundred pounds each, and when the West Indians arrived there was a bonanza of room-letting which started the later immigrants off on the worst possible foot. A few of these African pioneers, now long dispersed, became adept at handbag-snatching with violence, the crime we now refer to as 'mugging'. It has always seemed strange to me that articulate men, agreeable drinking companions, could behave in such an evil fashion. A secret room in a basement belonging to a promi- nent West African communist was found to be piled from floor to ceiling with discarded, ripped-apart handbags left there for safety by mugger friends. Mugging skills were not taught in Fagin style to West Indians, but / think that a tenuous thread can be traced backwards from today's English-born mugger to the adventurers from Lagos, Freetown and Bathurst.

Some African muggers remain in 1-00- don, such as 'Big Jimmy', who claimed that he only snatched the bags and disapproved of the way his partner knocked the old ladies down and kicked them 'real hard'. As I left his council tenement, generally believed to be a 'blacks only' block, I notic- ed an empty handbag on the stairs.

It is an odd fact that coloured people on council lists tend to be placed all in the same flats or streets, regardless of what part of town they lived in before. One who can read upside down, a happy gift when deal- ing with officialdom, told me that a form marked 'Ethnic Origin' is used by housing officials, who look at you and then put a ring round a certain number. 'Black estates' seem less cared for than the others and, worst of all, they allow young people to grow up in ignorance of the outside world, which they often regard as alien, threaten- ing and extremely rich.

Typical West Indian parents in Britain today are 'English black' in their ways, with none of the peasant-like, almost Elizabethan turns of speech and nuances of thought which their own parents brought here. Real West Indians are growing old, and the present middle-aged generation Mostly came here when they were ten years old or so, in the Sixties. They were sent for by their far-off and half-forgotten parents, and left their kindly grandparents behind in the Caribbean with many regrets. Their ex- pectations of British life were somewhat squashed when they found that they were expected to act as babysitters for their Younger brothers and sisters while their Parents went out to work. Disoriented, not to say thoroughly irritated, they are now Parents themselves, and their children may be muggers. Some hold decidedly anti- white views, as they never wanted to come here in the first place, and now are neither West Indian nor truly British. Folklore and love of Empire are vanishing with the old People, and being replaced by a 'blacks against whites' view of mankind, which is Passed on to the children and left uncheck- ed in the schools. Little Africa has become ulaek London.

Although babies are much fussed over in West Indian homes, older children are often treated with a surprising lack of im- agination. Even now they are given few toys and seldom read to or played with, but sat in front of the television instead. This may keel) them happy, but it often fills their minds with a confusion of dream-images. %4, Y mother always brought me up right,' Sister Muriel of the Feet Washing Baptists told me. 'She never let 'Me go out to play with other children, but always showed me how to work around the house. It's wrong to let children play.' All work and no play makes Rudie a bad boy when he finally grows too big to be contained at home. However, children of Vest Indian origin often do not know how to Play. Children's playgrounds are ig- -, „°red, when they can go out alone, in favour of reggae shops and pool halls where they jive around as if adult, from eight

years old upwards. Given toys, they do not know what to do with them. Parents are fiercely resentful of any outside advice on bringing up children, and sometimes insist on an arbitrary 'discipline' which can drive the children to secrecy, slyness and dishonesty.

This is changing slowly. Affectionate fathers, often church-goers, can now be seen holding hands with their children on the street, a sight at one time unheard of. My middle-aged acquaintance Sebastian is a more typical father. When at home with his family he has a peevish, embarrassed air, obviously feeling he has been 'trapped'. Morosely, he obeys his strident wife and looks forward to his escape to a disco, where he will behave as if happily single once more.

Sebastian told his children that when they left school they would be doctors and lawyers, if only they passed their exams. Eventually, just able to read and write, the children left their comprehensive school proudly clutching Grade Four CSEs, aglow with the praise their teachers had heaped on them out of misplaced kindness. Stunned, the youngsters found that they were only offered unskilled jobs. Their state of mind was that of a middle-class boy from a secure background who studies hard and con- fidently expects to go to college. Then, in a flash, all his achievements are gone and he is magically changed to an illiterate who can only succeed by brute strength or crime. While in this shattered state of mind, the young Sebastians were chased out of doors by their furious parents for letting them down, and told never to come home again. They wound up in Muggers' Alley by way of the local community centre. Now they too are parents.

It is ironic that the cure for mugging is seen as more and more black youth centres, as these centres themselves become focal points for muggers, who spring out from their shadows upon the unwary passers-by. A Jamaican housewife I know, who lives in Lewisham, blames the vast new centre in Pagnell Street for luring her children into a life of crime. She intends to take a milk- crate, the Eighties' equivalent of a soap- box, to Speakers' Corner and there de- nounce the director of the centre. 'Our children are brainwashed in this country, taught nothing but black politics instead of Christianity,'' she told me. 'Why are they always taught they belong to Africa? They are English, not African, and Rasta is nothing but witchcraft.'

The muggers' territory which I know best stretches from Notting Hill to Harlesden. Learning judo or carrying paint sprays is of little use, as the muggers strike suddenly from behind, travelling silently in rubber- soled shoes and seemingly appearing from nowhere. Nor is it any use carrying money in a handy packet for them to take, as their motive is partly revenge on a world they cannot understand, and their victims are pushed or tripped over and then kicked thoroughly. Lone women, of any age or colour, are the usual targets, and the at- tackers are normally ordinary-looking negro boys working singly or in twos and threes. Rastas do not seem to mug people, on the whole. At night the streets are so empty that muggers would have to rob each other, but in fact all the attacks I have heard about at first hand have taken place in broad daylight. Passers-by often prefer not to become involved.

After an attack on an old lady of 84, the consensus in our paper shop was that hang- ing should be reintroduced for muggers, but the Indian behind the counter surprised us by saying that they should have their hands cut off. Severe punishments of a more orthodox kind may prove to be the answer, but the police are stymied by the fact that black youths seem so alike to out- siders.

Elderly white Londoners, who once feared West Indians for no very good reason, now behave as if shell-shocked, and jump at the slightest noise. I cannot blame them, but all this is hurtful for the majority of young coloured people who were born here and who do not go a-mugging. It can be very upsetting if you smile at someone or ask them the time and they cringe back in terror. Notwithstanding all the success stories, let alone Black Power, carnivals and riots, many Londoners of West Indian descent seem to me to be essentially the same confused, helpless people their grand- parents were, standing aghast on railway platforms as night slowly fell.

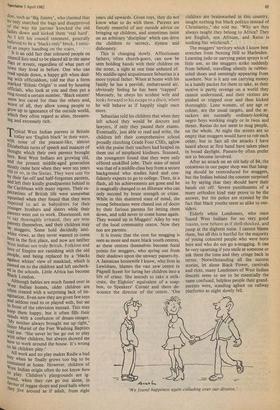

'We found happiness again colluding over our divorce.'

Previous page

Previous page