GONE WITH THE LIMBS

Simon Sebag Montefiore on being an

extra in the film that was too shocking for Hollywood's most risque actress

LAST WEEK, the voluptuous actress Kim Basinger, 39, who masturbated with con- siderable chic in her film 9"2 Weeks, was ordered by a Los Angeles court to pay £6 million to the makers of a film called Box- ing Helena for breaking her promise to play the film's lead. Basinger, naturally, is appealing. As it stands, the award revolu- tionises the way business is done in Holly- wood: 'A verbal contract ain't worth the paper it's written on,' as Sam Goldwyn put it. The real winner is Boxing Helena. Already one of the most disturbing films ever made, its place is now guaranteed in Hollywood's Valhalla as the film so shock- ing that even Kim Basinger did not dare make it.

I was in Atlanta, Georgia, last summer on the set of the film, in which I ended up appearing as an extra. Since the themes of Boxing Helena are sexual obsession and adventure, total possession, murderous insanity and physical amputation, the set was haunted by just about every crazed demon the warped minds of Beverly Hills have ever imagined. Life on the set was pure Edgar Allan Poe.

The hot Southern nights were prowled by two shadowy spectres: Kim Basinger, the cursed star, whose betrayal was to be avenged by a lawsuit no one on the set thought they would ever win — and the box which was to hold the limbless torso of a living sacrifice to love: Helena.

I read the script on my first night in Atlanta: Helena (Sherilyn Fenn, star of Twin Peaks, and Basinger's replacement), a cruel Southern beauty, enjoys a one- night stand with an intense but brilliant surgeon (Julian Sands) who falls in love with her. She torments him and is then hit by a car. He claims it is necessary to ampu- tate her legs. He operates on her in his house and, to keep her there, he places her in a box. But she is defiant. So he ampu- tates her arms. But she is still defiant.

When I arrive, the proud local papers are claiming that this film resembles another Atlanta love story — Gone With the Wind. The parallel is far-fetched: if anything, this is 'Gone with the Limbs', though the script, surprisingly well written, is not a cheap horror story but an erotic, if warped, manifesto of love.

My first hint that there are some odd forces at work occurs when I visit the pro- ducer's office: the room is dominated by a huge, wooden crate, larger than a coffin, standing upright, reinforced by steel, sealed with chains. I try to open this mor- bid object. A production assistant rushes up to me. 'You cannot see it,' she says. 'It is the Box.'

`The box?'

`The Box of Helena,' she says as if it is a mythical wonder of the ancient world. `Can I see it?'

The young lady places her body between me and the Box.

`No one can see it. No one sees it!'

Then the door opens. Enter a dark, grim-faced man, wearing a broad-brimmed fedora hat and a sinister dark suit, like a character out of Little Caesar.

`Are you the producer?' I ask.

`I'm his father,' snaps the man gruffly. He looks at the crate. `Ah. The Box.' He smiles and leaves.

Outside the set, a huge, bespectacled man with a bushy black beard in a volumi- nous pair of shorts that reach below his hirsute knees is striding up and down, sweat marks soaking patches into his shirt. He is bellowing into a tiny cordless tele- phone that appears too small to consume sounds from such a titanic source. This is the embattled producer, Carl Mazzacone, who devoted six years (and all his money) to the film. He turns to me: 'I've lost all my dough. But my paycheck's in the glory!' Then he resumes shouting into the phone.

The set is ruled by the rakish, red-haired, cowboy-booted Jennifer Lynch, only 24, who grew up on the set of her father David's weird movies (Blue Velvet is one) and who wrote the script when she was only 19. She supervises the 'grips', the bare- chested helots of film-making, who are des- perately converting a local bar called Otto's into a set, hanging upside down from lad- ders, hysterically waving hammers and microphones. Lynch sports a tattoo on her arm that reads 'Hollywood Underground'.

A handsome, lone figure, in a colonial linen suit, eyes staring, lean-jawed, strands of blond hair hanging over his face, walks intensely through the crowd like a man who has just amputated the perfect limbs of a lissome young starlet. A young extra, a local drama student, follows the master with admiring eyes as if he is walking on water: 'Look at Julian Sands,' he whispers. `He lives the part of Nick. He lives the part! Lives it!'

A diminutive, New York publicist named Mira Tweti guides me through the mob up to Jennifer Lynch, who says in a gravelly voice, 'This film is not to offend, that's too easy; what's the fun of that? — it's to pro- voke, to turn on, to tell a story. That is the point of films.'

`Can I see the Box?' I ask.

`No one sees the Box until it's time,' she says ominously. 'Right on! Let's go. Let's shoot!'

The place dissolves into manic activity: `You're on camera, asshole,' an assistant director snarls. I seem to have a talent for wandering on camera, a most unpopular habit.

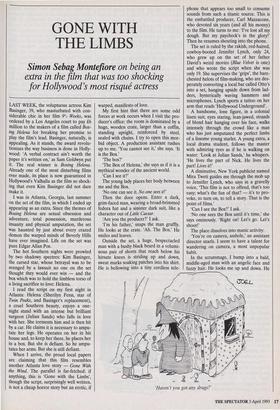

In the scrummage, I bump into a bald, middle-aged man with an angelic face and fuzzy hair. He looks me up and down. He 'Haven't you got any drugs?' appears very familiar. 'I'm Art Garfunkel,' says the voice of Simon and Garfunkel. The actor and singer, who plays the ampu- tator's best friend, stares into my eyes and adds mystically, 'You have a nice sympa- thetic face. Come! Follow me.' I follow him into the street. 'I was scared by the script,' he thinks aloud, 'but not scared off. This was one of the best things I've read, so I did it.' A young blonde drives up, wearing a miniskirt and cowboy boots. 'My wife, Kim,' says Garfunkel softly. 'Just got married.'

`This movie's kinda spooked,' says Sergeant Harp, a towering Southern cop with walrus moustaches, ivory-handled pis- tol, sunglasses and cavalry boots. `Somethun a-do wit a box. I seen it. Not a million miles from a coff-in!' His job is to guard the stars. He wears a 'Pistol Expert' badge (`Yessir! That's better than a Marksman'). He knows a star when he sees one but is a little confused about his histo- ry of rock. He watches Art Garfunkel, twirls his moustaches, saying innocently, `Fine voice, fine voice. He sang "Ain't Got No Satisfaction" like a bird! '

The cameras are cocked; the grips are off camera; Miss Lynch looks at her watch; the cherubic Garfunkel and the Rasputin- eyed Sands are ready.

`Where's Sherilyn? Sherilyn!' yells the young director: time is scarce; money scarcer.

Miss Fenn, leggy but soon to be limbless, walks barefoot onto the set, auburn tresses flying behind her, accompanied by a very Hollywood character: her Official Best Friend and Resident Masseur (or as she says it `Mazooze), Susan Gale Linn. Miss Linn hands me a bit a paper that claims she has massaged everyone from Meryl Streep to Richard Gere. Miss Fenn looks over at her Official Best Friend and hisses, `Get over here!' Susan Linn • runs. When she returns, the Official Best Friend says, `I'm her Best Friend, you know. Would you like a massage? I've done Richard Gere.' Then Miss Fenn, who is as slinky as a lynx, says, 'Where's the English writer? Drinks at seven,' she tells me. 'Shoot,' shouts director Lynch: the mad surgeon meets his friend in an Atlanta bar — and glimpses Helena.

It is afternoon. Mira Tweti, the publicist, is briefing me about my drink with Fenn. It's my first time on a film set. 'You'll grow up one day,' Mira assures me. 'Not neces- sarily,' interrupts Art Garfunkel, who pops up beside us. 'It didn't work like that for me.'

`Have you seen the Box?' I ask Gar- funkel.

He does not seem to hear.

`Powerful material,' he says.

The impressed acting student rushes up to me and whispers, `Julian's becoming his part!' before he is off again to observe his idol.

Once again, I blunder on camera. The assistant directors are beside themselves. But the director, our jolly young tyrant, says kindly, 'If you wanna be in Boxing Helena, you're in it, baby. Last scene tonight.' Meanwhile, Mazzacone is still shouting outside. The Box casts its long shadow and Julian Sands, an Englishman in a very American asylum, dreams of cricket. 'Cricket's the most relaxing way to get away from it all. It's a leveller.'

But when he talks about the film, Sands calls it 'a curious, cosy love story: a varia- tion of boy meets girl; boy loses girl; boy gets girl back. A feel-good movie.' How well he understands the surgeon's mad- ness: 'Her legs and arms are distractions that attract flies as if they are smeared with honey.' His eyes are Nick's eyes now. So why does he amputate Helena's limbs? He pauses. 'They are in the way.'

`God help us. He is Nick now,' mutters the acting student.

I am in a bar across the road with Sheri- lyn Fenn. We sip margaritas. Sergeant Harp stands at attention with his back to us, thumbs in his gunbelt.

When Miss Fenn raises her glass to her lips, I notice that the white skin of her wrists is bruised black and blue from the rough sex scenes.

`The bruises are on my arms,' she says, `but they're Helena's bruises. That scared the hell out of me! Entering the eye of the storm.' She fears the Box: 'I get weird and claustrophobic. I have that strength in me but I'm like Helena too in that I'm pretty vulnerable. I never thought I'd make it to here.' Then she turns to a vague but encouraging reminiscence of her youth: `When I was ten years old, I was pinning down boys and kissing them.' Then her psychic connection to England: 'I can do a perfect English accent. A psychic tells me I'm drawn to England.'

Sergeant Harp barks that it is time for another scene. He escorts us back.

Wouldn't-ya mind keeping that fox in a box?' he whispers to me loudly behind the peak of his cap as he watches the Fox in a Box in her armless, backless dress, a cruci- fix at her throat.

Fenn takes me to her special caravan to be made up. Inside this filmset shrine, there are just a lot of clothes, a tape- recorder, a jungle of hairsprays — and some photographs of Fenn in states of undress. I sit down in the next-door chair to Fenn. 'You better get made up for your scene,' she says. A make-up artist violently applies greasy foundation. Official Best Friend asks: Did you interview my Best Friend? Hasn't she got a perfect body?'

It is 2 am. Everyone is exhausted, but Carl Mazzacone, who has paced up and down screaming into his contraption all day and is still going strong, wants to push on until dawn. The actors and grips are tired. The 24-year-old writer-director is as enthu- siastic and patient as ever, but pale from the strain of her responsibility and lack of sleep.

`Just remember,' she laughs. The good sex in this script is all mine!' As for Kim Basinger and Madonna, the stars who let the film down, 'They hadn't done enough investigating of the little girls inside them- selves. Feminists are gonna love this film!' She is hoarse but the cast are waiting. 'All right,' she says to me, 'are you ready for your star-studded first appearance in the world of movies? I'll place you myself.' She puts me in a chair next to Fenn. 'Good place, eh? Right on!'

Even in a film as weird as Boxing Helena, the glamour of my 15 seconds of stardom soon begins to fade: my job is to sit beside Fenn and pretend to talk to the student who worships Julian Sands while I sip a foul brew of Coca-Cola and tepid water from a soiled glass. Then Fenn stands up, walks over towards the camera. This might sound like an easy one but it took about three hours to shoot. It is almost dawn by the time we finish. Nothing seems strange any more: not the Box, not the amputa- tions and not the curse of Kim Basinger. Finally, I am so thirsty under the burning lights that I drink the whole concoction in my glass. As the director yells 'In the can!' she and Fenn run at each other across the set, singing a song and dancing what appears to be a Hollywood can-can.

At 4 in the morning, the strange cast staggers out into the streets: Mazzacone is still shouting into a phone. Lynch, exuber- ant as ever, says, 'After that performance, you'll never end up on the cutting-room floor!' Outside, Sergeant Harp watches Sherilyn disappear down the empty street. `Phew,' he twangs, wiping his broad brow. `Tell me, are the cops you have in London armed?' The Official Best Friend (and Mazooze) announces, 'I've rubbed Richard Gere's lumbar region.' Garfunkel confides, `Simon, there's something in your face that reminds me of me when I was your age. Something.' One thing is certain: with its bizarre story, its free publicity and its record as the brave little film that defied the money men and the star system, Boxing Helena is in line for an Oscar next year. After all, it has everything a hit film needs. Except legs.

Previous page

Previous page