WAITING FOR A HUNDRED YEARS

Philip Hensher lists the similarities between the end of the 20th and of the 19th centuries. There is a craving for a new genius. Meanwhile, Damien Hirst is our Beardsley, Trainspotting's author is our Zola

I am talking, of course, about the 1890s. There are strange and pervasive connections to be made between the end of the last century and the end of this. Some, of course, are mere coin- cidence, like the relative posi- tion of the Queen and of Queen Victoria; with some, the analogy has to be stretched too far; too much has to be omitted to make any sense of the comparison (turmoil in southern Africa, an uncertain political situation in Russia). But in other ways — the ways which we usually mean when we talk about the fin de siècle (the lily-buttonholed aes- thete, the comfortable dabbling painter producing dank canvases about the operas of Wagner) — there are profound connec- tions to be made. Above all, it seems that the pressure the approaching turn of the century has on the productions of the mind is working in an unexpectedly similar fash- ion. In art, in literature, in music, it may come to seem that we are living among artists who mirror, with startling fidelity, the gritty realists, the ironists and aesthetes of the 1890s.

The idea of the fin de siècle is an old and powerful one; though we may have left behind the terrors of the millennium — the superstitions about inauspicious numbers, for instance, which led to fears of the apoc- alypse before the year 1000 — the approaching turn of the century still exerts a pull on creative artists. 'I thought Millen- nium would be wonderfully bold,' Martin Antis wrote in the preface to London Fields, speculating about alternative titles for the novel. '(A common belief: everything

is called Millennium just now).' The dim feeling that here, approaching rapidly, is the close of an epoch, a chance to make a statement of complete newness, starts to pull on artists, it's safe to say, years before the clocks tick round their shiny zeros. The sheer depressive boredom of trying to cre- ate something innocently new, that hasn't been done before in the 96th year of a cen- tury, may act as a psychological pressure on artists. Just as strong is the nervous pres- sure that something new must be achieved — a new Thomas Mann must show himself, a new Picasso, or, for the 1890s, a new Beethoven, a new Keats. And around the Nineties, a restlessness starts to manifest itself, in case a new genius doesn't turn up. The sense that the sheer newness of an artist who arises in the first decade of a new century is somehow redoubled, as if the birth of a century confirms and adds lustre to the birth of a new art, is not one that can be justified; and yet art which is created at the beginning of a century has an unmistakable excitement and energy. It is as if a Beethoven or a Wordsworth at the beginning of the 19th century, or a Picasso or a Proust at the beginning of the 20th, were aware that here was a chance to forge not just a new symphony, a new painting, a new novel, but a bigger, more innocent adventure, a chance to create a new century.

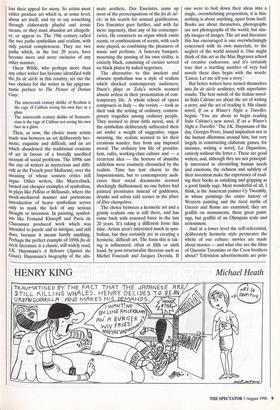

But waiting for that adven- ture to begin, waiting for the great leap forward some unimagined genius might take, the artists of the fin de siècle find themselves, often, in an unsatisfactory sort of position. It's not that they can't do any- thing new; it's that, mentally working at the end of an exhausted century, they have lost their innocence, the spirit of discovery. If there is one single factor which unites the creative artists of the 1890s and the 1990s, it's being utter- ly jaded and cynical. The pre- dominant mood is one of irony and scepticism; the character- istic work of art is one which decorates and embellishes works of art that are already there. It might be the decorative curlicues of Aubrey Beardsley, or, in our case, Damien Hirst, restating the most ancient and familiar themes of the visual arts death, decay and immortality — with hope- less, redundant forcefulness. The result, in both periods, is art of great appeal and ele- gance; it is also, however, art which has lost the urge to do something profoundly origi- nal rather than just original in its manner. There is a choice here that artists who feel themselves unable to venture into something terrifyingly new must make. Both at the end of the 19th century and at the end of this, art and literature seem to have to move forward by one of two means. The ordinary means of art seem to have

lost their appeal for many. So artists must either produce art which is, at some level, about art itself, and try to say something through elaborately playful and ironic means, or they must abandon art altogeth- er, or appear to. The 19th century called the two paths symbolism and realism, with only partial completeness. They are two paths which, in the last 20 years, have become more and more exclusive of any other manner.

Oscar Wilde, who perhaps more than any other writer has become identified with the fin de siecle in this country, set out the two choices for the writer in his epigram- matic preface to The Picture of Dorian Gray: The nineteenth century dislike of Realism is the rage of Caliban seeing his own face in a glass.

The nineteenth century dislike of Romanti- cism is the rage of Caliban not seeing his own face in a glass.

Then, as now, the choice many artists made was between an art deliberately her- metic, exquisite and difficult, and an art which abandoned the traditional evasions of art in favour of a brutally unedited account of social problems. The 1890s saw the rise of writers as mysterious and diffi- cult as the French poet Mallarme, over the meaning of whose sonnets critics still argue. Other writers, like Maeterlinck, turned out cheaper examples of symbolism, in plays like Pelleas et Melisande, where the mock-mediaeval manner and portentous introduction of heavy symbolism serves only to mask the lack of any serious thought or invention. In painting, symbol- ists like Fernand Khnopff and Puvis de Chavannes produced work which was intended to puzzle and to intrigue, and still does, because it means hardly anything. Perhaps the perfect example of 1890s fin de siecle literature is a classic, still widely read, J.K. Huysmans's A Rebours (Against the Grain). Huysmans's biography of the ulti- mate aesthete, Des Esseintes, sums up most of the preoccupations of the fin de sie- cle; in his search for sensual gratification, Des Esseintes goes further, and with far more ingenuity, than any of his contempo- raries. He constructs an organ which emits scents, or combinations of scents, with each note played, so combining the pleasures of music and perfume. A funerary banquet, mourning the passing of his own virility, is entirely black, consisting of caviare served on black plates by naked negresses.

The alternative to this insolent and obscure symbolism was a style of realism which shocked contemporary audiences; Ibsen's plays or Zola's novels seemed almost artless in their presentation of con- temporary life. A whole school of opera composers in Italy — the verists — took as their task the setting of ordinary, contem- porary tragedies among ordinary people. They seemed to draw little moral, and, if the symbolists deliberately suffocated their art under a weight of suggestive, vague meaning, the realists seemed to let their creations wander, free from any imposed moral. The ordinary low life of prostitu- tion, cafés, working-class culture and — a recurrent idea — the horrors of absinthe addiction were routinely chronicled by the realists. Time has lent charm to the Impressionists, but to contemporary audi- ences their social documents seemed shockingly disillusioned; no one before had painted prostitutes instead of goddesses, drunks and urban café scenes in the place of fetes champetres.

The choice between a hermetic art and a grimly realistic one is still there, and has come back with renewed force in the last 20 years. It's taking a different form this time. Artists aren't interested much in sym- bolism, but they certainly are in creating a hermetic, difficult art. The form this is tak- ing is influenced, often at fifth or sixth hand, by post-structuralist theorists such as Michel Foucault and Jacques Derrida. If one were to boil down their ideas into a single, overwhelming proposition, it is this: nothing is about anything, apart from itself. Books are about themselves, photographs are not photographs of the world, but sim- ply images of images. The art and literature this has encouraged is one overwhelmingly concerned with its own materials, to the neglect of the world around it. One might think of this art as the Max Bygraves school of creative endeavour, and it's certainly true that a startling number of very bad novels these days begin with the words: `Listen. Let me tell you a story.'

But better writers have turned themselves into fin de siecle aesthetes, with superlative results. The best novels of the Italian novel- ist Italo Calvino are about the act of writing a story, and the act of reading it. His classic novel, If on a Winter's Night a Traveller, begins: 'You are about to begin reading halo Calvino's new novel, If on a Winter's Night a Traveller.' The J.K. Huysmans of the day, Georges Perec, found inspiration not in the human dilemmas around him, but very largely in constructing elaborate games, for instance, writing a novel, La Disparition, entirely without the letter e. These are good writers, and, although they are not principal- ly interested in chronicling human needs and emotions, the richness and subtlety of their invention make the experience of read- ing their books as satisfying and gripping as a good family saga. Most wonderful of all, I think, is the American painter Cy Twombly, in whose paintings the entire history of Western painting and the tired myths of Greece and Rome are examined; they are graffiti on monuments, these great paint- ings, but graffiti of an Olympian scale and seriousness.

And at a lower level the self-referential, deliberately hermetic style permeates the whole of our culture: movies are made about movies — and what else are the films of Quentin Tarantino or the Coen brothers about? Television advertisements are prin- cipally about other television advertise- ments. This mistrust of real experience is the sign of a disinclination to take anything seriously. The best works of art which have this quality of self-referentiality, like Twombly, are nothing if not serious; it's a quality, though, peculiarly open to abuse by the idle and the cynical. These exercises in abstruseness, as with the aesthetes of the 1890s, produce some awful, self-regarding rubbish; they have also produced some masterpieces. The 1890s, quite apart from all the posturing, produced Mallarme we have the works of Calvino.

The alternative an artist faces, it seems, if he doesn't want to produce something play- fully self-referential, is exactly what it was in the 1890s. With great sophistication, he can produce a work which mimics the lack of any art whatsoever. The interesting case here is the film-maker Ken Loach. In his films, such as Raining Stones, or Ladybird Ladybird, he goes to great lengths to imitate the texture of a home-made movie, as if this was a way to put real life onto celluloid. With consider- able and conscious artistry, his films are built out of half-finished conversations, the appearance of randomness, like the product of eavesdropping. In reality, these richly tex- tured melodramas construct a brilliant facade, an illusion of reality, an aesthetic style which convinces audiences of their sin- cerity. These new realists, like the old ones, try to persuade their audiences that they are concerned with ordinary lives and ordinary people. In fact, just like the sensational com- posers of verismo opera in the 1890s, they are interested in the extraordinary; not absinthe addiction, as in Zola, but heroin addiction, as in Irvine Welsh's Trainspotting. The American writer Raymond Carver may be the single most influential writer of the new realist school; he himself was scrupu- lously modest about his ambitions, but his followers, while retaining his pared-down, American vernacular style, have used the blunt manner for sensationist plots which no Gothic novelist could improve upon. I said earlier that the predominant mood of the age was one of irony and scepticism; the realists, in their proclaimed lack of faith in the former powers of art, their new faith in the contrived appearance of the slapdash, seem no less ironic and sceptical than a writ- er like Perec.

It's not altogether a healthy situation, the fin de siecle, and the sense of a great swarming mass of activity in the arts but no visionary figure to make a leap forward into something entirely new is not, at the moment, an encouraging one. But we might take comfort — in contemplating the divide between an over-refined, post-post- structuralist, fancifully self-referential man- ner and an affected and excessive realism — in thinking that something very like this has happened before, and, no doubt, some- thing like it will happen again. The similari- ties between political events in the 1890s and now, which I began with, are genuinely coincidental, though, in some ways, amusingly striking. The coincidences between the art of 100 years ago and ours, on the other hand, go deep, and suggest that artistic invention may go through cycles; perhaps, more surprisingly, that the cycles may be tied to that most arbitrary of external events, the turning of the year, and the century.

Of course, this is an argument about taste; it's not an argument about the art itself, but the art which the fin de siecle val- ued and promoted. It wasn't that there were no original artists working at the end of the 19th century, it was that taste was so sophisticated and adulterated that, in many ways, it could only notice and value the sophisticated and adulterated in art. Noth- ing could be more innocently new, more radically unlike the decorative style of the average fin de siecle painter than Cezanne, but he had to wait until the new century to be recognised. It's not incredible that something similar is happening now. It might be that some modern azanne is working somewhere, now, in SW2 or Kreuzberg or even — there is nothing cer- tain about genius — in the shadow of azanne's own Mont St Victoire. What does seem to me to be pretty likely is that,

if there is someone changing the funda- mentals of the art, as Beethoven did, or azanne, or the Romantic poets, he might well have to wait for the end of a jaded decade for anyone much to notice.

Dominic Prince's article (The truth about the loss of royalties; 27 July) wrongly stated that he co-founded the Motor Neurone Dis- ease Association. The charity was in fact founded by Mr Prince's father.

Previous page

Previous page