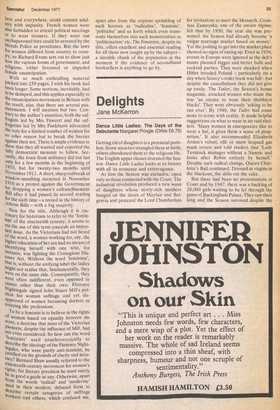

Delights

Jane McKerron

Dance Little Ladies: The Days of the Debutante Margaret Pringle (Orbis £6.75) Getting rid of daughters is a perennial problem. Some societies strangled them at birth; others abandoned them to the religious life. The English upper classes invented the Season, Dance Little Ladies looks at its history with all its nonsense and extravagance.

At first the Season was exclusive, open only to those connected with the Court. The industrial revolution produced a new wave of daughters whose newly-rich mothers banged on the doors of Mayfair and Belgravia and pestered the Lord Chamberlain for invitations to meet the Monarch. Countess Zamoyska, one of the ancien regime, felt that by 1930, the year she was presented, the Season had already become 'a vulgar marriage market based on money'. Yet the jostling to get into the market place showed no signs of easing up. Even in 1939, events in Europe were ignored as the deb's mums planned bigger and better balls and cocktail parties. They were shocked when Hitler invaded Poland — particularly on a day when Searcy's order book was full — but despite the cancellations they did not give up easily. The Tatter, the Season's house magazine, attacked women who made the war 'an excuse to wear their shabbiest blacks'. They were obviously 'asking to be run over'. By 1940, the Taller had come more to terms with reality. It made helpful suggestions on what to wear in air raid shelters. 'Many women in emergencies like to wear a hat, it gives them a sense of proportion.' It also recommended Elizabeth Arden's velvet, silk or snow leopard gas mask covers and told readers that 'Lady Tavistock manages without a Nannie and looks after Robin entirely by herself.' Despite such radical change, Queen Charlotte's Ball continued, Dressed as virgins in the blackout., the debs cut the cake.

But there had been no presentations at Court and by 1947, there was a backlog of 20,000 girls waiting to be let through the gates of Buckingham Palace. They saw their king and the Season survived despite the continuance of rationing and the threatening presence of Mr Attlee's Government. Hostesses become most inventive, producing large luncheons on black market eggs, dried fruit and mayonnaise mixed with liquid paraffin. Despite the risk of poisoning, the girls should have a good time with the right chap at the end of it.

The 'fifties were the heyday of the 'open season'. Virtually any middle-class girl could 'come out' even if it meant hiring some elderly aristocrat lady to sponsor her. They did not come cheap. Unlike the champagne, still only 21s a bottle. A decent supper could still be provided for 8s 6d a head. Tommy Kinsman, the 'in' band leader, complained that too many debs 'fell in love' with him. Not surprising, as the 'fifties were also the decade of the deb's delight. Mark Chinnery, then a Guards officer, now a television director, recalls his deb days with a razor eye. 'That was the awful thing. All those wretched parents pouring money out for their daughters while we all behaved so badly.' The 'fifties also produced the 'Deb of the Year' to end all others, Henrietta Tiarks.

I was presented in the same year, 1957, but was never in the same league. I pounded round at the back of the field, always in the wrong hat and too fat to be fancied by anyone but desperate Dads worried dizzy by their bank balances. Presentation at Court ended in 1958, yet the Season limped on for another twenty years, through a series of faint death-knells. Lenare, who photographed countless debs, including myself, gazing mistily into the distance, closed in 1976. This year saw the last Queen Charlotte's Ball.

In her foreword to the book Henrietta Tiarks says of the Season: 'I'm glad I did it, but I would not want to re-live one solitary second of it.' She adds, that if she had a seventeen-year-old daughter now she would send her to university abroad. Apart from the cost of the Season, estimated at £20,000 in 1967, daughters as well as parents are becoming more reluctant. The eccentric idea that girls should be educated is established. May and June are for 0 or A levels, rather than for tea parties in Kensington Gore.

Margaret Pringle's book is a delight for those of us who trod the deb circuit and most educative for anyone foolish enough to envy us. It may look glossy but its text is shrewd. It is accurate social history.

The gossip columnists, always lurking at the tables of the rich, fed greedily for years off deb gossip. Nigel Dempster, though coming from the Australian backwoods where 'five was a crowd', was himself a `deb's delight' and floated happily through several seasons, picking up valuable contacts en route. As a columnist he now despises the whole scene. 'It was the upper classes trying to perpetuate their hoax upon the world to keep themselves to themselves.' But they failed. Too many others wanted in on the act. Mr Dempster should know. He helped promote them.

Previous page

Previous page