Assault on Harar

Anthony Mockler

The Ogaden war is a fascinating affair for the student of military history. It is, I think I am right in saying, the only open war directly involving two sovereign states now being fought in any part of an unusually peaceful planet. It is being fought over territories that have seen centuries of battle and bloodshed and have, ever since that notorious dispute over Wal-Wal in 1934, entered the realm of world politics rather than of mere local, tussles. It is being fought between two races that are by tradition proud and warlike — and by tradition hereditary enemies — the tall, nervy, highly egalitarian Somalis of the desert and the small, nervy, highly hierarchic Amhara of the mountains. And, most fascinating of all, it is a war whose outcome is very much in the balance.

But it has also been a most confusing war. Last week's acme of confusion over the fate of Harar (which led to The Times announcing the fall of the city one day only to backpedal smartly the next) has shown one thing( the absolute importance of the war correspondent being allowed to the front if any clear picture is to emerge. As it is, frustrated would-be war correspondents, kicking their heels in Nairobi and Mogadishu, have been sending in reports based on the worst traditions of Lord Copper's emissary — bazaar gossip, the secoad-hand reports of a telephone call,.the whisperings of an Arab ambassador, 'information' from official communiques which cannot be checked, or even inferences from the absence of official communiques.

In this obscurantism the Ethiopians have, understandably, been the worst offenders; but even the Somalis have allowed only a carefully conducted visit to captured Jijiga. Yet both sides would be served by opening up their fronts to proper correspondents: the Somalis would be able to prove the extent of their victories, which has been stunning; and the Ethiopians could demonstrate that they are not all cowards or fools (as most of the world must now be believing — except for those who know the Ethiopians and tbeir bravery at first hand) and could hope to win that sympathy which world opinion is prepared to give to the losing side in what has so far been an astonishingly one-sided war.

As it is, in the absence of objective reporting from either side of the front, all we can say with certainty is that the situation is highly confused and is likely to remain so for the moment. We know that the invading Somalis swept over the Ogaden desert right up to its outermost edge, Jijiga, almost without drawing breath. This was, if unex pected, understandable — conquerors, whether British, Italian or indeed Ethiopian, have always swept over the Ogaden desert pretty rapidly. There is nowhere that a 'line' can be held, and once one side has got the bit between its teeth, the other side tends to crumble — as indeed the Somalis may yet learn to their cost, if and when the long-expected Ethiopian counter-attack does materialise.

At Jijiga they should, by rights, have paused: this was the end of absolutely friendly, Somali-inhabited territory. Above them loomed the mountains, with a ' muslim but basically Galla population, difficult country, not unfriendly but by no means so welcoming as the desert. However the Ethiopian Third Division mutinied and broke; abandoned Jijiga, and, more impor tant, abandoned the Marda Pass, the gateway to the highlands, without a fight. (This has become clear thanks to the visit of the western correspondents to Jijiga. Incidentally, the Somalis announced they had captured Jijiga three weeks before they did so, and the Ethiopians said they were still in control two weeks after it had fallen which is why only a factual report from Harar on the spot can confirm the final truth of its fall, recapture or whatever).

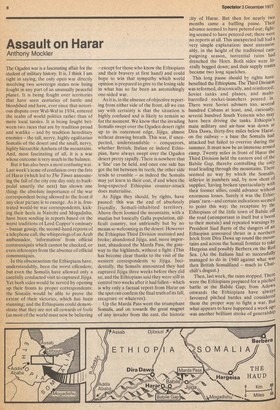

Up the Marda Pass went the triumphant Somalis, and on towards the great magnet of any invader from the east, the historic city of Harar. But then for nearly two months came a baffling pause. Their advance seemed to have petered out; fighting seemed to have petered out; there were no reports at all. This unexpected lull had a very simple explanation: most unreasonably, in the height of the traditional campaigning season, torrential rains had drenched the Horn. Both sides were literally bogged down; and their supply routes became two long squelches.

This long pause should by rights have benefited the Ethiopians. The Third Division was reformed, draconically, and reinforced; Soviet tanks and planes, and multibarrelled rocket-launchers poured in. There were Soviet advisers too, several hundred Cubans at least, and, curiously, several hundred South Yemenis who may have been driving the tanks. Ethiopia's main military and air-base was down at Dira Dawa, thirty-five miles below Harar, on the railway — a base the Somalis had attacked but failed to overrun during the summer. It must now be an immense armed camp. Twenty miles in front of Harar the Third Division held the eastern end of the Babile Gap, thereby controlling the only road leading through the mountains. There seemed no way by which the Somalia,, inferior in numbers and, by now short of supplies, having broken spectacularly with their former allies, could advance without enormous losses. Surely it was the Ethiopians' turn — and certain indications seemed to point this way: the recapture by the Ethiopians of the little town of Babile Of the road (unimportant in itself but a boost to their morale) and repeated warnings by President Siad Barre of the dangers of an Ethiopian armoured thrust in a northern hook from Dira Dawa up round the mountains and across the Somali frontier to take Hargeisa and possibly Berbera on the 'Zed Sea. (As the Italians had so successfullY managed to do in 1940 against what was then British Somaliland — much to Churchill's disgust.) Then, last week, the rains stopped. There were the Ethiopians prepared for a pitched battle at the Babile Gap; from Adowa onwards the Ethiopians have always favoured pitched battles and considered them the proper way to fight a war. BLit what appears to have happened a week ago was another brilliant stroke of generalshiP by the Somalis. The Babile Gap was defended; Dira Dawa was defended; but Harar, between the two, was almost undefended. There was no need to defend it, there was no way of launching a serious attack on it; or so the Ethiopians and their advisers appear to have thought. But it seems the Somalis, under cover of the foul weather, infiltrated parties of guerrillas through the almost impassable hills, and then, a thousand strong, dropped down on Harar from a totally unexpected side, the north-west. It seems so obvious now it has been done — but before that the Somalis had always advanced up the main road with armour and all conventional support. Their commanders seem to have almost the Ingenuity of the Israelis.

What now? In theory the Ethiopians seem to be adroitly cut in two; but by a much inferior force. They command the air, they now have the more powerful tanks. On the other hand this Somali coup, even if it does not last, must again have shaken the Morale of already badly shaken troops. And nothing is more demoralising than rumours of enemy in the rear, which inevitably lose nothing in the telling. As for all the new advisers and weapons, the technical confusion can only be equalled by the linguistic babel. And Harar, an Arab city of narrow streets, courtyards, and intricate patterns, is one from which guerrillas cannot easily be winkled out.

My feelings are mixed: three million Somalis against fifteen million Ethiopians, now heavily armed; surely they simply cannot go on and on! But they have so far; and of course they are united and the Ethiopians are not. Certainly if they establish themselves firmly in Harar, Dira Dawa down beneath it will become untenable. And if Dira Dawa falls, then the next line of defence is the Awash, only a hundred miles from Addis Ababa — and the limit of the territory the Somalis now claim.

On the other hand their bold stroke may have failed: and also, rumours of the fall of Harar, birthplace of the late Emperor, and third city of the Empire, may cause such rumblings in Addis Ababa that the apparent tension there Will erupt. This seems, at the moment, the likeliest outcome of the present conflict.

Previous page

Previous page