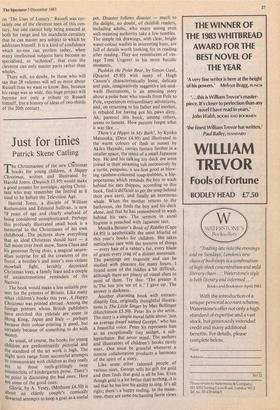

Early genius

Anthony Storr

The Collected Papers of Bertrand Russell, Volume 1: Cambridge Essays 1888-99 Edited by Kenneth Blackwell, Andrew Brink, Nicholas Griffin, Richard A. Rempel, John G. Slater (George Allen & Unwin [.£48 pre- publication] £60)

ertrand Russell lived from 1872-1970.

He wrote 70 books, and some 2,500 shorter pieces. His writing has always delighted me. Everything of his which I have ever read seems illumined from within by a glowing clarity. He is one of the great masters of English prose, and it is entirely apt that he should have been awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature.

The Collected Papers of Bertrand Russell, of which this is the first volume, will run to 28 volumes in all. The publishers hope to complete this massive undertaking by the year 2000. The papers are being edited by a team at McMaster University, Ontario which bought the Russell Archives in 1968. About one-third of the present volume consists of appen- dices: outlines of lectures; monthly lists of Russell's reading; annotations, text- ual notes, and a bibliographical, as well as a general index. It is clear that all the resources of modern scholarship are being employed to make this edition unrepeatably definitive. All in all, it looks as if we shall eventually have more information about Russell's mind and its furnishings than we shall have about any other eminent mind of the 20th century.

The introduction to this volume states: 'Writing came naturally to Russell in a manner that is nowadays rare.' Perhaps; but, in 'How I Write', Russell himself con- fessed that, when he was young, it was a long time before he was able to write without worry and anxiety. 'When I was young each fresh piece of serious work used to seem to me for a time — perhaps a long time — to be beyond my powers. I would fret myself into a nervous state from fear that it was never going to come right. would make one unsatisfying attempt after another, and in the end have to discard them all.' At last he discovered the virtue of incubation. If he left the problem to sim- mer, 'it would germinate underground un- til, suddenly, the solution emerged with blinding clarity, so that it only remained to write down what had appeared as if in a revelation.'

Only the professional philosopher can assess Russell's contribution to philosophy, but the greater part of his more popular writing is easily accessible to the layman. From the psychological point of view, this volume if full of interest, It begins with 'Greek Exercises,' a journal started when

Russell was 15, written in Greek characters for the sake of secrecy. This reveals a startl-

ing precocity and an early interest in many of the problems which were to preoccupy Russell for years. In June 1888 he writes: 'It is extraordinary how few principles or dogmas I have been able to become con- vinced of. One after another 1 find my un- doubted beliefs slipping from me into the region of doubt.' In an autobiographical talk delivered years later, Russell says that one of the two most important motives which impelled him to take up philosophy was 'the desire to find some knowledge that could be accepted as certainly true.' The other motive was to find some satisfaction for his religious impulses. These early diaries are much concerned with the om- nipotence of God, immortality, the origin of conscience and related problems.

There is no false modesty. 'I read an arti- cle in the Nineteenth Century today about

genius and madness, I was much interested by it. Some few of the characteristics men- tioned as denoting genius while showing a tendency to madness I believe 1 can discern in myself.' Among these are 'sexual pas- sion' and 'a desire to commit suicide.' Both impulses remained powerfully active in Russell for years. We are fortunate that the former impulse prevailed over the latter, which it did with vigour.

After 'Greek Exercises' comes the hither- to unpublished 'A Locked Diary' which Russell kept from 1890-94. Amongst much else, it records the ambivalence of his feel- ings toward Alys Pearsall Smith who became his first wife in 1894. His musical taste is as yet unformed, since Tosti's 'Goodbye' is reckoned 'absolutely perfect of its kind', in the same class as Shelley's lyrics.

Russell went up to Cambridge in 1890. In 1892 he was elected to 'The Apostles'. Six

of the papers he presented to this society have been preserved and are printed here. It was at meetings of 'The Apostles' that Russell encountered Whitehead, with

whom he wrote Principia Mathematica. Modern students of philosophy will find

that they are looking back towards a

vanished world, and may perhaps be en- vious of those who were engaged in the sub-

ject before J.L.Austin and A.J.Ayer had launched their assaults upon traditional metaphysics. 'It may be contended that,

although we can never wholly experience Reality as it really is, yet some experiences approach it more nearly than others, and such experiences, it may be said, are given by art and philosophy.'

Russell writes on Bacon, on Descartes, on Hobbes; on Ethics; on Free-Will; on

Geometry. It is astonishing that so much of his undergraduate and graduate work has been preserved. Did the lonely child who recorded that beginning Euclid was 'as

dazzling as first love' treasure these early In- tellectual exercises in the way that other adolescents treasure love-letters? By the mid-1890s, Russell had become interested in economics and politics. There is a paper on 'German Social Democracy,' and another on 'The Uses of Luxury.' Russell was cer- tainly one of the cleverest men of this cen- tury, but one cannot help being amazed at both his range and his mandarin certainty that he can master any subject to which he addresses himself. It is a kind of confidence which no-one can profess today, when many intellectual subjects have become so specialised, so 'technical', that even the cleverest can only master parts rather than wholes. There will, no doubt, be those who will say that 28 volumes will tell us more about Russell than we want to know. But, because his range was so wide, this huge project will become not only a tribute to Russell himself, but a history of ideas of two-thirds of the 20th century.

Previous page

Previous page