Arts

Glint and vigour

John McEwen

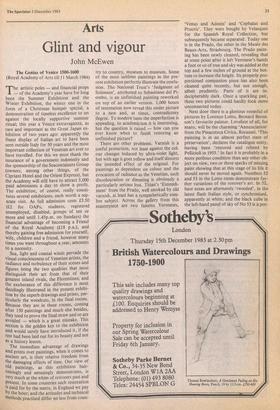

he artistic poles — and financial props — of the Academy's year have for long been the Summer Exhibition and the Winter Exhibition, the winter one in the form of a Christmas bumper special, a demonstration of timeless excellence to set against the locally supportive summer ritual; this year a Venice extravaganza, as rare and important as the Great Japan ex- hibition of two years ago: apparently the finest display of Italian art to have been seen outside Italy for 50 years and the most important collection of Venetian art ever to have travelled. For this we must thank the insurance of a government indemnity and the sponsorship of the Seacontainers Group (owners, among other things, of the Cipriani Hotel and the Orient Express), but the Academy will still have to attract 3,000 paid admissions a day to show a profit. The exhibition, of course, really consti- tutes several exhibitions, each worth a sep- arate visit. As full admission costs £3.50 (£2 for OAPs, students, registered unemployed, disabled, groups of ten or more and until 1.45p.m. on Sundays) the financial advantage of becoming a Friend of the Royal Academy (£18 p.a.), and thereby gaining free admission for yourself, wife, children and a friend, however many times you want throughout a year, amounts to a necessity.

Sea, light and coastal winds pervade the visual consciousness of Venetian artists, the radiance and turbulence of their scenes and figures being the two qualities that most distinguish their art from that of their greatest inland rivals, the Florentines; and the exuberance of this difference is most dazzlingly illustrated in the present exhibi- tion by the superb drawings and prints, par- ticularly the woodcuts, in the final rooms. Because they are in these rooms, coming after 150 paintings and much else besides, they tend to prove the final straw and so are

avoided — which is a great mistake. This section is the golden key to the exhibition and would surely have introduced it, if the rest had been laid out for its beauty and not as a history lesson.

The immediate advantage of drawings and prints over paintings, when it comes to ancient art, is their relative freedom from the damaging effects of time. Our view of old paintings, as this exhibition hair- raisingly and amusingly demonstrates, is very much at the whim of restorers past and present. In some countries such restoration is paid for by the metre, in England we pay by the hour; and the attitudes and technical Methods practised differ no less from coun- try to country, museum to museum. Some of the most sublime paintings in the pre- sent exhibition perfectly illustrate the confu- sion. The National Trust's 'Judgment of Solomon', attributed to Sebastiano del Pi- ombo, is an unfinished painting reworked on top of an earlier version. 1,000 hours of restoration now reveal this under picture to a new and, at times, contradictory degree. To modern taste the imperfection is appealing, to academicism it is interesting, but the question is raised — how can you ever know when to finish restoring an unfinished picture?

There are other problems. Varnish is a useful protection, not least against the col- our changes induced by ultra-violet light, but with age it goes yellow and itself distorts' the intended effect of the original. For paintings as dependent on colour and the evocation of radiance as the Venetian, such discolouration or dimming is obviously a particularly serious loss. Titian's 'Entomb- ment' from the Prado, well smoked by old varnish, at least has a sympathetically som- bre subject. Across the gallery from this masterpiece are two famous Veroneses, 'Venus and Adonis' and `Cephalus and Procris'. They were bought by Velasquez for the Spanish Royal Collection, but subsequently became separated. Today one is in the Prado, the other in the Musee des Beaux-Arts, Strasbourg. The Prado paint- ing has been newly cleaned, revealing that at some point after it left Veronese's hands a foot or so of tree and sky was added at the top and a few inches of ground at the bot- tom to increase the height. Its properly pro- portioned companion piece has also been cleaned quite recently, but not enough, albeit prudently. Parts of it are in- decipherably dark. Once a sparkling pair, these two pictures could hardly look more unconnected today.

Next door there is a glorious roomful of pictures by Lorenzo Lotto, Bernard Beren- son's favourite painter. Loveliest of all, for many, will be the charming 'Annunciation' from the Pinacoteca Civica, Recanati. 'This painting is in an almost perfect state of preservation', declares the catalogue entry, having been 'restored and relined by Pellicioli in 1953.' In fact it is probably in a more perilous condition than any other ob- ject on view, two or three specks of missing paint showing that at this stage of its life it should never be moved again. Numbers 52 and 53 in the Lotto room demonstrate fur- ther variations of the restorer's art. In 52, bare areas are alternately 'tweeded', in the latest flash Italian style, or synchronised, apparently at whim; and the black cube in the left-hand panel of sky of No 53 is a por- tion of uncleaned surface, left by the Italian restorer to show what a good job he has done. In England, to our credit, we disdain such theatricals.

Prints and drawings do not present these problems. They can often be as good as new and, particularly in the case of the prints, have been chosen to demonstrate it. They have also been chosen, first and foremost, for their beauty and not their historical im- portance. Hats off, therefore, to their bold selector David Landau, because if the exhibition sags in interest it is at about the half-way stage, when we come on rooms academically devoted to the painters not of Venice but the cities of the Italian mainland under Venetian rule. This is didactically acceptable because it enforces the point that Venice, in the 16th century, became more of a land and less of a sea power — suc- cessfully defending its Italian mainland territory, while relinquishing power in the East to the Turks and trade in the West to the Portuguese. Nevertheless, the inland painters can never be, with the exception of Jacopo Bassano (who is rightly given a room of his own), other than large fish in small ponds, landlocked from the airy space and sea-glint colour, the sea-wind vigour of the masters.

This glint and vigour is above all what the woodcuts have — an astonishing verve which makes it no surprise to find that for 30-odd years at the outset of the century the medium was a novelty practised by artists for its own sake and not just as a means of reproducing paintings. Here the brilliance of Giuseppe Scolari and Jacopo de' Barbari is triumphantly revealed, and Titian's supremacy once more confirmed by the 12-part 'Submersion of Pharaoh's Army in the Red Sea' — in the expert Landau's opi- nion, the greatest woodcut of all time. The fact that Titian's 'Flaying of Marsyas' in Gallery 3 must also be described as one of the greatest paintings of all time — and this review finds no space to discuss notable contributions by Giorgionc, Tintoretto and that sober roundhead of a painter Moroni, plus first-rate sculpture — alone should indicate what an exhibition of exhibitions this is.

Previous page

Previous page