Exhibitions 1

A Victorian Earl in the Arctic: The Travels and Collections of the 5th Earl of Lonsdale (Museum of Mankind, till 27 July)

Errant earl

John Hensh all

Collections of ethnographical artefacts have been gathered under strange cir- cumstances, but few can rival the pedigree of that brought back from the Eskimo and Athapaskan peoples of Alaska and the Yukon last century by Hugh Lowther, 5th Earl of Lonsdale. The 'Yellow Earl', so- called because of his predilection for the colour (he was first president of the AA, Which has painted everything yellow since), travelled to those distant parts to expiate his guilt over an all too public affair with an actress which led to an unpleasant courtroom encounter with an outraged husband.

Lonsdale sailed from Liverpool in February 1888 and returned 14 months later after travelling 10,000 miles. He presented the British Museum with some 200 items from a variety of Arctic peoples, including hunting gear, tools, waterproof Clothing, kayaks, amulets, carvings and dance masks. He also wrote a vivid diary, Parts of which might not be ideal reading for the Commission for Racial Equality. The exhibition at the Museum of Mankind (Burlington Gardens, W1) is absorbing — Yet hardly quite as intriguing as the story behind it. '

When Hugh Lowther became 5th Earl in 1878 he was already married, but this did hot curb his taste for fast living. His brazenly public liaison with Violet Carnet- On, who apparently knew little about acting but plenty about pulling men, made international headlines. Lonsdale was especially newsworthy because of the repu- tation he had gained for promoting boxing (hence the Lonsdale belts). The tale may

be apocryphal, but it is said that Queen Victoria told him to remove himself for a time to let the scandal subside. To the Arctic he went.

He travelled across some of the wildest parts of the Yukon and Alaska, then untouched by the Klondike gold-rush. The final stage across the Alaskan peninsula to Katmai was through deep snow by dog team. His reactions to the peoples he met were predictable for a traveller of his background at the time. He disliked the Athapaskans of the interior and called the Chipewyan 'dirty filthy brutes', while the Slavey were `a funny-looking lot'. But he admired the coastal Eskimo peoples, who were aggressive, courageous hunters — a role in which he fancied himself.

Lonsdale's ethnographical prejudices are reflected in the artefacts he collected from the various peoples he met. So are his personal interests — sport especially. The exhibition features quivers, darts, snares, knives and harpoons. He certainly in- dulged his sporting tastes, if that is quite the term: having stated before leaving England that he hoped to shoot a musk-ox, he ended up in a whale hunt which saw ten of the creatures killed. Greenpeace would have been waiting to lynch him on Liver- pool Docks.

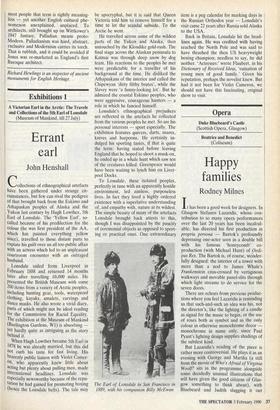

To Lonsdale, these isolated peoples, perfectly in tune with an apparently hostile environment, led aimless, purposeless lives. In fact they lived a highly ordered existence with a superlative understanding • of, and empathy with, nature at its wildest. The simple beauty of many of the artefacts Lonsdale brought back attests to this, though I was disappointed by the paucity of ceremonial objects as opposed to sport- ing or practical ones. One extraordinary The Earl of Lonsdale in San Francisco in 1889, with his companion Billy McEwan item is a peg calendar for marking days in the Russian Orthodox year — Lonsdale's visit came 22 years after Russia sold Alaska to the USA.

Back in Britain, Lonsdale hit the head- lines again. He was credited with having reached the North Pole and was said to have thrashed the then US heavyweight boxing champion; needless to say, he did neither. 'Actresses:' wrote Flaubert, in his Dictionary of Received Ideas, 'ruination of young men of good family.' Given his reputation, perhaps the novelist knew. But had it not been for Violet Cameron, we should not have this fascinating, original show to visit.

Previous page

Previous page