Russian revelations

Andrew Lambirth

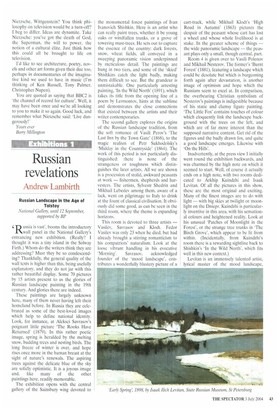

Russian Landscape in the Age of Tolstoy National Gallery, until 12 September, supported by BP

1119 ussia is vast', booms the introductory IN. wall panel in the National Gallery's entrancing new exhibition. (Really? I thought it was a tiny island in the Solway Firth.) Whom do the writers think they are addressing? Must they be so condescending? Thankfully, the general quality of the wall texts is higher than this, being usefully explanatory, and they do not jar with this rather beautiful display. Some 70 pictures by 15 artists present to us the glories of Russian landscape painting in the 19th century. And glories there are indeed.

These paintings are largely unknown here, many of them never having left their homeland before. In Russia they are celebrated as some of the best-loved images which help to define national identity. Look, for instance, at Aleksei Savrasov's poignant little picture 'The Rooks Have Returned' (1879). In this rather poetic image, spring is heralded by the melting snow, budding trees and nesting birds. The long freeze of winter is over, and hope rises once more in the human breast at the sight of nature's renewals. The aspiring trees against the delicate blue of the sky are solidly optimistic. It is a joyous image and, like many of the other paintings here, readily memorable.

The exhibition opens with the central gallery of the Sainsbury wing devoted to the monumental forest paintings of Ivan Ivanovich Shishkin. Here is an artist who can really paint trees, whether it be young oaks or windfallen trunks, or a grove of towering mast-trees. He sets out to capture the essence of the country: dark forests, snow, wheat fields, all conveyed in a sweeping panoramic vision underpinned by meticulous detail. The paintings are hung in two tiers, and some of the 'skied' Shishkins catch the light badly, making them difficult to see. But the grandeur is unmistakable. One particularly arresting painting, 'In the Wild North (1891), which takes its title from the opening line of a poem by Lermontov, hints at the sublime and demonstrates the close connections that existed between the artists and their writer contemporaries.

The second gallery explores the origins of the Russian landscape tradition, from the soft romance of Vasili Perov's `The Last Inn by the Town Gate' (1868), to the magic realism of Petr Sukhodolsky's 'Midday in the Countryside' (1864). The work of this period is not particularly distinguished: there is none of the strangeness or toughness which distinguishes the later artists. All we are shown is a procession of stolid, awkward peasants at work — fishermen, shepherds and harvesters. The artists, Sylvestr Shedrin and Mikhail Lebedev among them, aware of a lack, went on pilgrimage to Italy to drink at the fount of classical civilisation. It obviously did some good, as can be seen in the third room, where the theme is expanding horizons.

This room is devoted to three artists — Vasilev, Savrasov and Klodt. Fedor Vasilev was only 23 when he died, but had already brought a stirring romanticism to his compatriots' naturalism. Look at the loose vibrant handling in his evocative 'Morning'. Savrasov, acknowledged founder of the `mood landscape', contributes a wonderfully blustery picture of a cart-track, while Mikhail Klodt's 'High Road in Autumn' (1863) pictures the despair of the peasant whose cart has lost a wheel and whose whole livelihood is at stake. In the greater scheme of things — the wide panoramic landscape — the peasant plays only a small, though central, part.

Room 4 is given over to Vasili Polenov and Mikhail Nesterov. The former's 'Burnt Forest' (1881), featuring a landscape which could be desolate but which is burgeoning forth again after devastation, is another image of optimism and hope which the Russians seem to excel at. In comparison, the overbearing Christian symbolism of Nesterov's paintings is indigestible because of his static and clumsy figure painting. 'The Little Fox' contains touches of colour which eloquently link the landscape background with the trees on the left, and which are of far more interest than the supposed narrative content. Get rid of the figures and the badly drawn fox, and quite a good landscape emerges. Likewise with 'On the Hills'.

Inadvertently, at the press view I initially went round the exhibition backwards, and was charmed by the high note on which it seemed to start. Well, of course it actually ends on a high note, with two rooms dedicated to Arkhip Kuindzhi and Isaak Levitan. Of all the pictures in this show, these are the most original and exciting. Many of the finest images are to do with light — with big skies at twilight or moonlight on the Dniepr. Kuindzhi is particularly inventive in this area, with his sensational colours and heightened reality. Look at his unusual 'Patches of Moonlight in the Forest', or the strange tree trunks in 'The Birch Grove', which appear to be lit from within. (Incidentally, from Kuindzhi's room there is a rewarding sightline back to Shishkin's 'In the Wild North', which fits well in this new context.) Levitan is an immensely talented artist, lyrical master of the mood landscape, adept at light effects and exact description, though often rendered in a sketchy, even Impressionistic, manner. His work is refreshing and inspiring, and rightly is he seen as one of the greatest masters of the Russian school. This stimulating exhibition would be worth visiting for acquaintance with him alone, but the whole extent of it is a revelation. What a coup it would have been for the Tate to have timed its impressive exhibition of the American Sublime (which actually took place two years ago) to coincide with this stunning exhibition of Russian landscape. Détente through art? It would certainly have been a splendid opportunity to compare and contrast — and to understand both countries that much better.

Previous page

Previous page