SINKING THE BOAT PEOPLE

Vietnamese refugees were once the the sufferings they undergo today

THOUSANDS upon thousands of boat People are still pouring out of Vietnam and across the South China Sea. They are being murdered, raped, pillaged, locked in camps and cages. And almost nothing is being said.

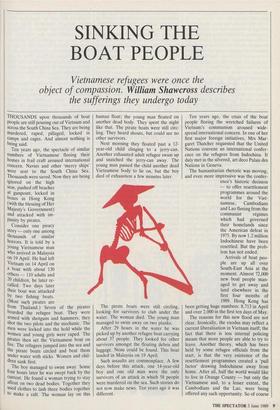

The boy managed to swim away. Some four hours later he was swept back by the current. He found a woman trying to stay afloat on two dead bodies. Together they used clothes to lash three bodies together to make a raft. The woman lay on this human float; the young man floated on another dead body. They spent the night like that. The pirate boats were still circ- ling. They heard shouts, but could see no other survivors.

Next morning they floated past a 12- year-old child clinging to a jerry-can. Another exhausted adult refugee swam up and snatched the jerry-can away. The young man passed the child another dead Vietnamese body to lie on, but the boy died of exhaustion a few minutes later.

The pirate boats were still circling, looking for survivors to club under the water. The woman died. The young man managed to swim away on two planks.

After 29 hours in the water he was picked up by another refugee boat carrying about 37 people. They looked for other survivors amongst the floating debris and luggage. None could be found. This boat landed in Malaysia on 19 April.

Such assaults are commonplace. A few days before this attack, one 14-year-old boy and one old man were the only survivors of an attack in which 58 people were murdered on the sea. Such stories do not now make news. Ten years ago it was different. Ten years ago, the crisis of the boat people fleeing the wretched failures of Vietnam's communism aroused wide- spread international concern. In one of her first major foreign initiatives, Mrs Mar- garet Thatcher requested that the United Nations convene an international confer- ence on the refugees from Indochina. It duly met in the silvered, art deco Palais des Nations in Geneva.

communist regimes which had governed their homelands since the American defeat in 1975. By now 1.2 million Indochinese have been resettled. But the prob- lem has not ended.

Arrivals of boat peo- ple are up all over South-East Asia at the moment. Almost 72,000 new boat people man- aged to get away and land elsewhere in the first four months of 1989. Hong Kong has been getting huge numbers: 8,713 in April and over 2,000 in the first ten days of May.

The reasons for this new flood are not clear. Ironically, the exodus may reflect a current liberalisation in Vietnam itself; the fact that there is less internal policing means that more people are able to try to leave. Another theory, which has been held by some refugee officials from the start, is that the very existence of the resettlement programmes created a 'pull factor' drawing Indochinese away from home. After all, half the world would like to live in Orange County — but only the Vietnamese and, to a lesser extent, the Cambodians and the Lao, were being offered any such opportunity. So of course thousands jumped and, despite the dan- gers, still jump at it.

On this theory, the news has now got through to Vietnam that the resettlement programme is finally ending and that now is the last chance. Resettlement in the developed world has slowed and so the numbers of people stuck in South-East Asian camps are rising. This the govern- ments of the region will not tolerate; they are acting rough. Resettlement is ending because of their much noticed phe- nomenon of the 20th century, compassion fatigue, which is very often fatal.

Like Aids, compassion fatigue is a con- temporary sickness. The symptoms are first a rush of concern for a distant and obviously suffering group, followed by tedium, withdrawal and even disdain. It is nurtured by the speed of communications, which bewilders and disorients people everywhere. In 1979 the boat people seemed to help to prove that although America had lost the Vietnam war, it had been right about its human consequences. Now, and perhaps particularly after Gor- bachev, such a crusade is rather passé. Instead of being praised as lovers of democracy, the Vietnamese are denounced for merely wanting a better life, a more Western life, a life of upward mobility. These days US navy ships and those of other nations do not seek to save boat people; they might hand over water and a few snacks and then push derelict sinking Vietnamese boats away.

Many of those who actually manage to land in Thailand have been literally pushed back out to sea by Thai police and fisher- men. Hundreds have drowned as a result. Those who have reached Hong Kong are clapped into prison. Now they are being repatriated. Hong Kong seems to be the model to which other South-East Asian nations now aspire.

There are now 10,000 Vietnamese im- prisoned in loathsome and intolerable con- ditions in Hong Kong. Families are con- fined in cages piled on top of one another. One camp is an old hangar stacked high with families. There is little light. Privacy is almost non-existent. The medical facilities are quite inadequate; there is a lot of sickness amongst children and babies. Some Vietnamese have been there for seven years now. And there is no depar- ture in sight.

All are subject to long screening inter- views supposed to determine whether they are genuine refugees or mere 'economic migrants'. In a world ever shrinking and more interdependent this is often a hard distinction.

'Everyone has the right to seek and to enjoy in other countries asylum from persecution,' according to Article 14 (1) of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. And the definition of a refugee under the 1951 Covenant is 'a person who, owing to a well founded fear of persecution for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion, is outside the country of origin and unable or, owing to such fears, unwilling to return to it'.

Under interrogation in Hong Kong, Vietnamese boat people must seek to prove that they can be thus described. But many of them seem to have little idea that these interviews are crucial to their future. The screening process appears to he per- functory at best. According to the British Refugee Council, the interpreters offered them are 'simply not good enough' and the Vietnamese are often not given enough time to prepare themselves for the inter- rogation. They are given no help nor any representation.

By the middle of last month only two out of more than 500 families screened had been granted asylum. Another 48 were found eligible for resettlement abroad be- cause they already had families in exile. The rest have been put back into prison as 'economic migrants' — as if to be that was to have committed a criminal offence. The truth of the matter is that 1979's refugees from communist tyranny are 1989's econo- mic migrants. It is we, our political fads and emotional enthusiasms, that have changed, not something strictly Viet- namese.

Those who come today talk of vast corruption and appalling bribery in Viet- nam. They say that there are no jobs available and that anyone connected with the ancien regime of South Vietnam still has difficulty in getting work or papers. Persecution and arbitrary imprisonment differ from province to province. In some areas, Catholics are still being forced to renounce their religion.

The poverty of the country is extraordin-

ary, particularly when contrasted with the wealth of the rest of South-East Asia today. Refugee officials in Hong Kong were struck by the lament of a deputy foreign minister who flew, officially, to Hong Kong to negotiate the voluntary return of refugees; he said that he had to have a second job as a carpenter in order to be able to sustain his family. One refugee worker who has interviewed several hun- dred boat people in Hong Kong says, `The overwhelming picture they paint of Viet- nam is one of chaos.'

In Hong Kong, refugees are allowed to appeal (there is no appeal against being driven off Thai beaches at gunpoint) and almost all those rejected are indeed appealing. But no appeals have yet been heard, and it is clear that the process will be grotesquely long. The British Council for Refugees warns that at the present rate people will be waiting another seven years — indeed, they may not even have their appeals heard before Hong Kong is handed back to China in 1997! So for the next nine years all these people will be living in boxes, if the present procedures continue. This is an outrageous prospect.

China's hostility lies behind this, as behind so many other problems of Hong Kong. A senior official of China's Hong Kong and Macao Affairs Office recently warned Hong Kong that it was not being tough enough on the Vietnamese and that none must be left behind in 1997. Li Hou, the deputy director of the office, said that it was an insult that when Chinese flee into Hong Kong they are arrested and handcuf- fed and deported back to China — yet there were no handcuffs for the Viet- namese. Such criticisms appear to be an interference in Hong Kong's internal affairs, but the response of the Hong Kong government was timid, as it so often is in the face of China. China, like the West, is hypocritical about the Vietnamese; in the late Seventies China welcomed them; now Peking sees no political advantage in generosity. Assuming that there is indeed a legiti- mate distinction to be drawn between people who genuinely fear persecution and those who merely despair of poverty at home, even if not so harshly drawn as in Hong Kong at the present time, what is to be done with or for those people screened out — those who fail the tests? Recently a group of 75 Vietnamese agreed to return home from Hong Kong under the auspices of the UN High Commissioner for Re- fugees. Another 75 or so were waiting to go. But the vast majority appear to prefer the cages of Hong Kong. What can happen to them?

In an attempt to find an answer, a new UN conference is about to be convened in Geneva. It will be very different from that of 1979; indeed it is supposed to put a clear end to the Indochinese resettlement prog- ramme. A preparatory meeting was held in Kuala Lumpur in March. The governments represented produced a 'Draft Compre- hensive Plan of Action' which called for more active screening, and more active resettlement, away from South-East Asia, of those who are determined to fit the description adequately.

But the rub comes with those who do not fit the bill. 'In the first instance every effort will be made to encourage the voluntary return of such persons.' And, if they did not choose to go quietly? 'If, after the passage of reasonable time, it becomes clear that voluntary repatriation is not making suffi- cient progress towards the desired objec- tive, alternatives recognised as being acceptable under international practices would be examined.' But what those would be is left deliberately ambiguous. 'A re- gional holding centre under the auspices of the UN High Commissioner for Refugees may be considered as an interim measure for housing persons determined not to be refugees pending their eventual return to the country of origin.' And what does that mean? Forced repatriation. The Governor of Hong Kong, Sir David Wilson, was even bold enough to spell out this threat earlier this year. Then he stepped back a bit. But the threat remains.

Forced repatriation used to be the dir- tiest word in the refugee handbook. All officials of the High Commissioner's office are taught that they must always do every- thing to protect refugees from 'refoule- ment', the technical term. I remember officials standing with their arms out- stretched in front of Thai soldiers trying to force Cambodians back into the land of the Khmer Rouge. The last time forced repat- riation was officially embraced by Western governments was after the second world war when the allies shipped back to Stalin's embrace scores of thousands of Soviet citizens who had been captured by the Nazis. The Russians insisted that only war criminals would not wish to return home. Most of those sent back were murdered or locked up. Then, when the idea of a new United Nations agency to help refugees was debated in San Francisco, Moscow refused to support any organisation which Was not concerned with repatriation and repatriation alone. So far such notions have been the prerogative of totalitarian rdgimes. Now, though, the boot is not on the totalitarian foot; Hanoi has refused to accept the boat people sent back by force. It is contemptible that nonetheless the British or Hong Kong governments should even consider forced repatriation of people who are in no way criminals but have merely 'got on their bikes' in a fashion which is applied elsewhere.

The executive committee of the High Commissioner's office has appealed to governments to recognise that the fact of seeking asylum should not be seen as a crime. That is the least of it. But ultimately there will be no solution except one de- vised between Vietnam, its neighbours and the rest of the world. If it is true that the majority of boat people are feeling pover- ty, then the obvious answer is to try to help alleviate that poverty. Since 1979 Vietnam has been pushed into international isola- tion and economic deprivation as punish- ment for its intransigence over Cambodia. Under economic pressure and that of Gorbachev, that intransigence has now ended; Vietnamese troops will be with- drawn this year.It is time that Vietnam, and Cambodia, were brought back into the international system. Massive international aid and investment are needed. Only then will the boats be used for fishing instead of flight. In the meantime the rights of those who have already fled, to Hong Kong and elsewhere, must be protected much more rigorously than is now the case.

Previous page

Previous page