THE HIGH COST OF HUMAN EXHALE

Britain's biggest landowner, the Duke of

Buccleuch, complains to Simon Courtauld

about the state's attitude to stately homes

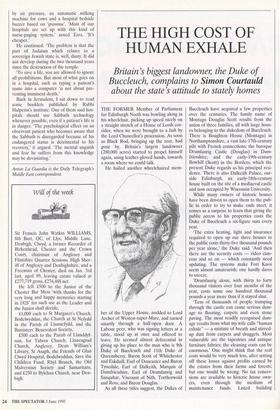

THE FORMER Member of Parliament for Edinburgh North was bowling along in his wheelchair, picking up speed nicely on a straight stretch of a House of Lords cor- ridor, when we were brought to a halt by the Lord Chancellor's procession. As soon as Black Rod, bringing up the rear, had gone by, Britain's largest landowner (280,000 acres) started to propel himself again, using leather-gloved hands, towards a room where we could talk.

He hailed another wheelchaired mem- ber of the Upper House, nodded to Lord Archer of Weston-super-Mare, and turned smartly through a half-open door. A Labour peer, who was signing letters at a table, stood up at once and offered to leave. He seemed almost deferential in giving up his place to the man who is 9th Duke of Buccleuch and 11th Duke of Queensberry, Baron Scott of Whitchester and Eskdaill, Earl of Doncaster and Baron Tynedale, Earl of Dalkeith, Marquis of Dumfriesshire, Earl of Drumlanrig and Sanquhar, Viscount of Nith, Torthorwold and Ross, and Baron Douglas.

As all these titles suggest, the Dukes of Buccleuch have acquired a few properties over the centuries. The family name of Montagu Douglas Scott results from the union of three families, all with large hous- es belonging to the dukedom of Buccleuch. There is Boughton House (Montagu) in Northamptonshire, a vast late-17th-century pile with French connections; the baroque Drumlanrig Castle (Douglas) in Dum- friesshire; and the early-19th-century Bowhill (Scott) in the Borders, which the present Duke regards as his principal resi- dence. There is also Dalkeith Palace, out- side Edinburgh, an early-18th-century house built on the site of a mediaeval castle and now occupied by Wisconsin University.

While many owners of historic houses have been driven to open them to the pub- lic in order to try to make ends meet, it comes as a surprise to learn that giving the public access to his properties costs the Duke of Buccleuch a six-figure sum every year.

`The extra heating, light and insurance required to open up our three houses to the public costs thirty-five thousand pounds per year alone,' the Duke said. 'And then there are the security costs — video cam- eras and so on — which constantly need updating. The systems make Fort Knox seem almost amateurish; one hardly dares to sneeze.

Drumlanrig alone, with thirty to forty thousand visitors over four months of the year, costs some one hundred thousand pounds a year more than if it stayed shut.

`Tens of thousands of people tramping through the castle can cause serious dam- age to flooring, carpets and even stone paving. The most readily recognised dam- age results from what my wife calls "human exhale" — a mixture of breath and stirred- up dust from carpets and druggets. Most vulnerable are the tapestries and antique furniture fabrics; the cleaning costs can be enormous.' One might think that the real costs would be very much less, after setting off these losses against profits earned by the estates from their farms and forests; but one would be wrong. No tax conces- sions are available to historic house own- ers, even through the medium of maintenance funds. Listed building allowances are denied to them, and they are ineligible to benefit from the National Lottery's Millennium Fund.

`We do have a thoroughly oppressive tax system,' the Duke said. 'Conservative gov- ernments are too frightened to be seen to be supportive of people like me. They would rather let such houses crumble.' The Duke expressed his concern, in a letter to The Spectator in 1993, that Mr Major's vision of a classless society would threaten the structure of enlightened management of the rural community, of which he is a notable exponent.

He is not whining when he points out how much it costs him to provide what amounts to a public service, but he does allude to the effect on local employment if he were compelled to close the doors of Drumlanrig. He has already been obliged to restrict the public opening of Bowhill and Boughton to one month a year, though they can be visited at other times by specialist groups (Sotheby's holds art study courses at Boughton). So why does the Duke continue to subsidise public access to his houses?

`I have long believed that the creators of works of art intended them to live along- side other works in their proper historical setting. Pictures, tapestries, furnishings, furniture, china, glass, silver should be in homes, castles and sometimes churches not in sanitised isolation in museums and galleries.

`If one is lucky enough to inherit a great collection, one feels one ought to be shar- ing it with others who derive cultural and spiritual nourishment and pleasure from seeing it in its proper context. But then it does seem rather a waste of time when people come to a house interested only in looking at a photograph of Douglas Fair- banks.'

If you stand beneath a chandelier weigh- ing nine stone in the staircase hall at Drumlanrig, you can look at a Holbein portrait, a Leonardo and a captivating Rembrandt, 'Old Woman Reading', Bowhill has Guardis, Canalettos, Claude Lorrains and Raeburns. At Boughton there are paintings by El Greco, Murillo, Teniers and some 50 oil sketches by Van Dyck — not to mention the collections of English and French furniture, and Sevres and Meissen porcelain, in all three houses.

None of the houses was opened to the public until after the Duke's father's death in 1973, when the top level of estate duty was 80 per cent. So the present Duke effectively owns only one fifth of the value of his great collections and the Treasury owns the rest. (Under the estate duty rules operating at that time, he is not obliged to open his houses to the public.) 'There are still pink politicians who clamour for a wealth tax, oblivious to the fact that a sav- age wealth tax has been operating for much of this century'. By another iniquity of the fiscal system, however, the Duke of Buccleuch is liable to pay not 20 per cent but the total cost of conserving these works of art.

`Say I have three pictures worth ten thousand pounds each, and the restoration cost of one is four thousand pounds. To pay this I need to sell the other two for a total of twenty thousand pounds to pro- vide me with my 20 per cent (four thou- sand pounds), while the Treasury takes the rest.'

After more than 20 years without gov- ernment assistance — he was granted a mere £20,000 for the 19-year programme of reroofing Drumlanrig and restoring its stonework — the Duke of Buccleuch remains philosophical. At the age of 71 it was a hunting accident not infirmity that put him in a wheelchair — he leaves the lobbying for long-overdue tax concessions to the Historic Houses Association. Mean- while, he devotes much of his time to improving understanding between town and country.

The Duke also holds estate open days, tb explain the workings of the countryside — including farming, forestry and game- keeping — to schoolchildren who, as he says, 'will learn about rain forests at school but not about what is happening five miles away'. About 1,500 children attend these open days at Boughton; eight- to ten-year- olds are apparently the most receptive.

`During thirteen years as an MP for a city centre, I was as struck by the lack of understanding of the countryside and its management among my fellow MPs as among my own constituents. Today the country representation in the House of Commons is much smaller, and the under- standing even less.' But he acknowledges the country, or at least equestrian, qualifi- cations of Robin Cook, the shadow foreign secretary. 'He had the cheek to stand against me at Edinburgh in the 1970 elec- tion,' he recalls with amusement.

As the Duke wheeled himself away down the corriddi to another appointment — he is president of the disability charity Radar — I reflected that we are fortunate to have such a public-spirited figure who is prepared to share his treasures with us, at his own expense. Such nobility, however, is to be expected from someone who has affiliations with the royal House of Stuart. The Duke of Buccleuch is directly descended, through both his parents, from Charles II.

`Forget the kids – he wants to stay together for the sake of the tax-breaks. ..'

Previous page

Previous page