C. S. LEWIS

This is the first in our Lent series on English spiritual writers.

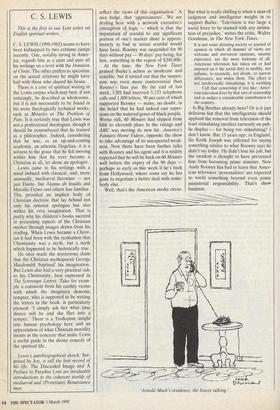

C. S. LEWIS (1898-1963) seems to have been kidnapped by two extreme camps recently. One, notably strong in Amer- ica, regards him as a saint and puts all his writings on a level with the Imitation of Christ. The other prefers to speculate on the sexual relations he might have had with those who shared his house.

There is a core of spiritual writing in the Lewis corpus which may best, if not enticingly, be described as wholesome, but it is not necessarily to be found in his more theologically technical works, such as Miracles or The Problem of Pain. It is certainly true that Lewis was not a professional theologian, though it should be remembered that he trained as a philosopher. Indeed, considering that he was, as an up-and-coming academic, an atheistic Hegelian, it is a witness to the grace that he felt moving within him that he ever became a Christian at all, let alone an apologist.

Lewis came to his writings with a mind imbued with classical, and, more unusually, mediaeval literature — not just Dante, but Alanus ab Insulis and Marsilio Ficino and others less familiar. This provided an implicit body of Christian doctrine that lay behind not only his rational apologias but also within his very imagination. That is partly why his children's books succeed in presenting aspects of the Christian mythos through images drawn from his reading. When Lewis became a Christ- ian it had been with the realisation that Christianity was a myth, but a myth which happened to be historically true.

He once made the mysterious claim that the Christian mythopoeist George Macdonald 'baptised' his imagination. But Lewis also had a very practical side to his Christianity, best expressed in The Screwtape Letters. Take for exam- ple a comment from his earthly victim with which the imaginary demonic tempter, who is supposed to be writing the letters in the book, is particularly pleased: 'I simply ask her what time dinner will be and she flies into a temper.' There is a Trollopian insight into human psychology here and an appreciation of what Christian morality means in the concrete that make Lewis a useful guide in the divine comedy of the spiritual life.

Lewis's autobiographical sketch, Sur- prised by Joy, is still the best record of his life. The Discarded Image and A Preface to Paradise Lost are invaluable introductions to the coherent worlds of mediaeval and (Protestant) Renaissance men.

Previous page

Previous page