Private faces in public places

John McEwen

PAINTINGS IN THE MUSEE D'ORSAY by Robert Rosenblum

Stewart, Tabori & Chang (distributed by Little, Brown and Co), £50, pp.686

he conversion of the Gare d'Orsay into the Musee d'Orsay was officially unveiled in December 1986. Now we have the grand guide to the collection, comprising 96 essays and 849 coloured illustrations, 22 of them supplementary enlargements of de- tails. It is not the whole works but certainly heavy enough in weight to sink an elephant. In Rosenblum's view the Museum is now the 'grandest international statement of what might be called a Post- modernist view of 19th-century art'. Natur- ally he is all for this. Bunging together the paintings of the academics along with those of their deadly avant-gardist rivals is, in his view, a turn for the better. Instead of perpetuating a battle of defunct ideologies, we now have the opportunity to make connections, to contrast and compare with a dispassionate eye. He acknowledges a fear on the part of 'purists' that this mixing together of the exalted and the mediocre may lead to 'familiar deities' being 'sullied' and Insulted'; but he does not reveal whether this fear has been realised and explores critical reaction no further.

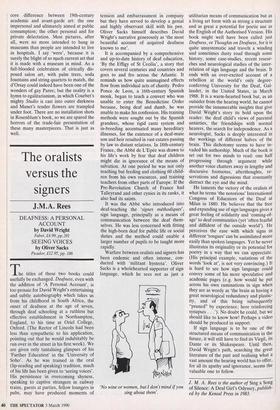

This may be understandable, is certainly tactful, but misses the point. The d'Orsay is iniquitous precisely because it betrays the principles of so many of the artists it commemorates. In doing so it exposes the 'Portrait of Emile Zola' by Edouard Manet, 1868 core difference between 19th-century academic and avant-garde art: the one impersonal and ultimately aimed at public consumption; the other personal and for private delectation. Most pictures, after all, were no more intended to hang in museums than people are intended to live in hospitals. I say 'were', because it is surely the blight of so much current art that it is made with a museum in mind. As a full-blooded celebration of civically dis- posed salon art, with palm trees, soda fountains and string quartets to match, the d'Orsay could indeed have been one of the wonders of gay Paree; but the reality is a hymn to egalitarianism, in which Courbet's mighty Studio is cast into outer darkness and Manet's tender flowers are trampled under foot. There are no installation shots in Rosenblum's book, so we are spared the horrors of the trade-fair presentation of these many masterpieces. That is just as well.

Previous page

Previous page