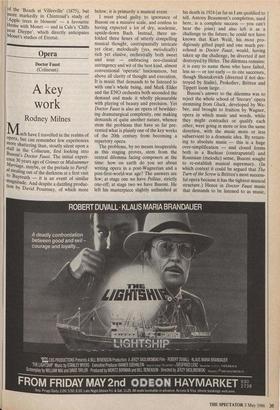

0 era

Doctor Faust (Coliseum)

A key work

Rodney Milnes

Much have I travelled in the realms of opera, but can remember few experiences more shattering than, stoutly silent upon a stall in the Coliseum, first looking into Busoni's Doctor Faust. The initial experi- ence 30 years ago of Grimes or Midsummer Marriage, maybe, or the prelude to Parsif- al stealing out of the darkness at a first visit to Bayreuth — it is an event of similar • magnitude. And despite a dazzling produc- tion by David Pountney, of which more below, it is primarily a musical event.

I must plead guilty to ignorance of Busoni on a massive scale, and confess to having expected a lot of dry, academic, upside-down Bach. Instead, there un- folded three hours of utterly compelling musical thought, contrapuntally intricate yet clear, melodically (yes, melodically) rich yet elusive, orchestrally both sweet and sour — embracing neo-classical astringency and wit of the best kind, almost conventional `operatic' lusciousness, but above all clarity of thought and execution. It is music that demands to be listened to with one's whole being, and Mark Elder and the ENO orchestra both seconded the demand and made it wholly pleasurable with playing of beauty and precision. Yet Doctor Faust is also an opera of bewilder- ing dramaturgical complexity, one making demands of quite another nature, whence stem the problems that have so far pre- vented what is plainly one of the key works of the 20th century from becoming a repertory opera.

The problems, by no means insuperable as this staging proves, stem from the central dilemma facing composers at the time: how on earth do you set about writing opera in a post-Wagnerian and a post-first-world-war age? The answers are few; at stage one we have Pelleas, strictly one-off; at stage two we have Busoni. He left his masterpiece slightly unfinished at his death in 1924 (as far as I am qualified to tell, Antony Beaumont's completion, used here, is a complete success — you can't hear the joins) and also left it as a challenge to the future; he could not have known that Kurt Weill, his most pro- digiously gifted pupil and one much pre- echoed in Doctor Faust, would, having taken up the challenge, be diverted if not destroyed by Hitler. The dilemma remains: it is easy to name those who have failed, less so — or too early — to cite successes, though Shostakovich (diverted if not des- troyed by Stalin), Prokofiev, Britten and Tippett loom large.

Busoni's answer to the dilemma was to reject the whole school of `literary' opera stemming from Gluck, developed by We- ber, and brought to fruition by Wagner, opera in which music and words, while they might contradict or qualify each other, were going in more or less the same direction, with the music more or less subservient to a dramatic idea. By return- ing to absolute music — this is a huge over-simplification — and closed forms both in a Bachian (contrapuntal) and Rossinian (melodic) sense, Busoni sought to re-establish musical supremacy. (In which context it could be argued that The Turn of the Screw is Britten's most success- ful opera because it has the tightest musical structure.) Hence in Doctor Faust music that demands to be listened to as music, and hence virtually no concessions to dramatic coherence and form. Yet at the same time there proceeds a specifically 20th-century drama: what to do with hu- man knowledge when God is dead, which he wasn't quite when Goethe tackled Faust (though having just returned from re- seeing Piero's 'Resurrection' in Sansepol- cro, I'm not sure that the reports of His death haven't been greatly exaggerated).

Busoni is delightfully vague with sugges- tions as to what might be going on in long, wonderful stretches of non-vocal music. Mr Pountney and his designer Stefanos Lazaridis have met the challenge boldly, creating a tension between stage action and music that constitutes a powerful argument for non-literary musically dramatic opera. The set, a huge conglomeration of vertigi- nously tilted filing cabinets and a floor that is not always a floor, would suit Dr Mabuse as much as Dr Faust, and within it are paraded dramatic representations of poli- tical, psychological, philosophical and sci- entific concerns relevant to Busoni and us in a phantasmagorical variety of styles, from the sombre (the birth of Mephis- topheles is one of the most frightening things I have seen on any stage) to the agreeably grotesque (the song-and-dance interlude leading to the court of Parma would surely have delighted Busoni). The whole is informed with that powerful sense of theatre for which Pountney is justly prized. Given the simultaneous demands of the music, it is impossible to take it all in at first sitting. For instance, to a simple soul like me a red rubber ball is a red rubber ball, but Paul Griffiths in the Times reveals that what the reborn child-Faust is bouncing at the end is in fact a hydrogen atom, which puts the mockers on that nice, optimistic C-major close. On the other hand, it could just be a red rubber ball. I do hope so.

Having seen this extraordinary produc- tion half a dozen times, I might be more coherent about it, but meanwhile I can heap praises on the singers. How nice to see Thomas Allen, who if he chose could earn a blameless living singing Don Giovanni all round the world, instead sinking his teeth into one of the most demanding operatic roles ever written — a Siegfried for baritone in length and breadth — and singing with unfailing beau- ty and eloquence; in Graham Clark he has an amazingly versatile alter ego (it is not every Mephisto who is called upon to wear fishnet tights) and there are excellent performances from Eilene Hannan, back on top form and singing like a dream as the Duchess, Henry Newman (Soldier) and John Connell (Wagner).

This Doctor Faust, I repeat, has been for me one of the experiences of an opera- going lifetime, and I beg you not to think of missing it. It ranks with Goethe philo- sophically and with virtually every great composer you care to name musically. It is also riveting simply as theatre. Book now.

Previous page

Previous page