NO NEED TO RIG THE BALLOT

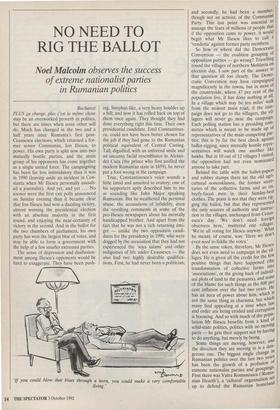

Noel Malcolm observes the success

of extreme nationalist parties in Rumanian politics

Bucharest PLUS cc, change, plus c'est la meme chose may be an overworked proverb in politics, but there are times when none other will do. Much has changed in the two and a half years since Rumania's first post- Ceausescu elections, which returned a for- mer senior Communist, Ion Iliescu, to power. His own party is split now into two mutually hostile parties, and the main group of his opponents has come together as a single united force. The campaigning has been far less intimidatory than it was in 1990 (leaving aside an incident in Con- stanta when Mr Iliescu personally assault- ed a journalist). And yet, and yet ... No sooner were the first exit polls announced on Sunday evening than it became clear that Ion Iliescu had won a dazzling victory, almost winning the presidential election with an absolute majority in the first round, and enjoying the near-certainty of victory in the second. And in the ballot for the two chambers of parliament, his own party has won the largest bloc of votes, and may be able to form a government with the help of a few smaller extremist parties.

The sense of depression and disillusion- ment among Iliescu's opponents would be hard to exaggerate. They have been push- ing, Sisyphus-like, a very heavy boulder up a hill; and now it has rolled back on top of them once again. They thought they had done everything right this time. Their own presidential candidate, Emil Constantines- cu, could not have been better chosen for the job if they had gone to the Rumanian political equivalent of Central Casting. Tall, dignified, with an unforced smile and an uncanny facial resemblance to Alexan- der Cuza (the prince who first unified the modern Rumanian state in 1859), he never put a foot wrong in the campaign.

True, Constantinescu's voice sounds a little timid and unsuited to oratory; one of his supporters aptly described him to me as sounding like John Major speaking Rumanian. But he weathered the personal abuse, the accusations of infidelity, even the revolting comments in some of the pro-Iliescu newspapers about his mentally handicapped brother. And apart from the fact that he was not a rich returning émi- gré — unlike the two opposition candi- dates for the presidency in 1990, who were dogged by the accusation that they had not experienced the 'soya salami' and other indignities of life under Ceausescu — the also had two highly desirable qualifica- tions. First, he had never been a politician; `If you could blow that blues through a horn, you could make a very comfortable living.' and secondly, he had been a member, though not an activist, of the Communist Party. This last point was essential to assuage the fears of millions of people that if the opposition came to power, it would begin what Mr Iliescu likes to call a `vendetta' against former party members.

So how or where did the Democratic Convention — the coalition grouping of opposition parties — go wrong? Travelling round the villages of northern Moldavia on election day, I saw part of the answer to that question all too clearly. The Demo- cratic Convention may have campaigned magnificently in the towns, but in most of the countryside, where 47 per cent of the population live, it has done nothing at all In a village which may be ten miles' walk from the nearest main road, if the cam- paign does not go to the villagers, the

vil-

lagers will never go near the campaign. Each polling station has a presiding com- mittee which is meant to be made up of representatives of the main competing par- ties: this is by far the best check against ballot-rigging, since mutually hostile repre- sentatives will watch one another like hawks. But in 10 out of 12 villages I visited, the opposition had not even nominated anyone to take part. Behind the table with the ballot-papers. and rubber stamps there sat the old agri- cultural nomenklatura, the former secre- taries of the collective farms and so on, beefy-faced men in their Sunday-best clothes. The point is not that they were rig- ging the ballot, but that they represented the only sources of authority and instruc- tion in the villages, unchanged from Ceaus- escu's day. 'We don't need foreign observers here,' muttered one villager. `We're all voting for Iliescu anyway.' What he meant, of course, was: 'Here we don t even need to fiddle the votes.' By the same token, therefore, Mr Iliescu does not even need to campaign in the vil- lages. He is given all the credit for the few positive things that have happened (the transformation of collective farms into `associations', or the giving back of individ- ual plots of land to the peasants), and none of the blame for such things as the 800 Per cent inflation over the last two years. He has an aura of power about him, which is not the same thing as charisma, but which many find appealing at a time when law and order are being eroded and corruption is booming. And so with much of the popu- lation Mr Iliescu benefits from a kind. of solid-state politics, politics with no moving parts — he gets their support not by having to do anything, but merely by being. Some things are moving, however, and the direction they are moving in is a dan- gerous one. The biggest single change to Rumanian politics over the last two years, has been the growth of a profusion or extreme nationalist parties and groupings. First there was Vatra Romaneasca (`Roma- nian Hearth'), a 'cultural' organisation set

. up to defend the Rumanian homeland

against the demands of ethnic Hungarians for such things as schools in their own lan- guage. Then there was Romania Uare (`Great [i.e. Greater] Rumania'), a weekly magazine packed full of articles about con- spiracies by Hungarians, Jews, Freema- sons, capitalists and the CIA. The magazine spawned its own political party, which now produces another weekly maga- zine, Politica (in whose latest issue I was proud to find myself mentioned as a small Fog in the great Jewish-Hungarian-capital- 1st engine of destruction). Then came the PUNR (Party of Rumanian National Unity), whose most prominent member, Gheorghe Funar, was elected mayor of the partly Hungarian town of Cluj, and pro- ceeded to ban the use of Hungarian on street-signs. Mr Funar, who describes Ceausescu as 'a good Rumanian' and criti- cises him only for having admitted ethnic Hungarians into the party nomenklatura in the Hungarian-speaking areas, was also a candidate in the presidential elections. He came third, with 12 per cent of the vote, and it is the transfer of those votes to 'Res- ell in the second round that will ensure Ili- escu's victory. The core of all these groups and parties and their many associated magazines and newspapers consists of old nomenklatur- ists, Securitate men and Ceausescu pro- teges. Reports in the West which refer to these parties as 'the extreme right' are mis- leading; their policy on the supposed Hun- garian menace is almost identical to that of the small Party of Socialist Labour, the final resting place of the hard-line Com- munists. Vatra Romaneasca, Romania Mare and the PUNR have nothing to do with right-of-centre conservatism: the clearest sign of this is their virulent opposi- tion to the idea of restoring the monarchy. Crude libels of King Michael and his fain,- IY litter the pages of their publications every week. Their main contribution to the election campaign has been to spread the rumour that the Democratic Convention was planning to do three things: to restore the monarchy, to reinstate feudal landown- ers, and to sell Transylvania to the Hun- garians.

Although the combined vote for these parties was little over 15 per cent, the effect they may have had in scaring ill-edu- cated Rumanians away from the Demo- cratic Convention is not so easily calculated. And now this so-called extreme right will join up with the left-over left of the old National Salvation Front (Mr 'Res- ell s party) to form a natural coalition. Nationalism and socialism can be a power- ful combination, as history has shown before; but the most powerful thing here is not an ism' at all. It is the desire of those hu have once experienced power not to lose it. In this, the old political class has Indeed displayed a truly national charac- teristic — that resourceful ingenuity of which Rumanians could once be justly

proud.

Previous page

Previous page