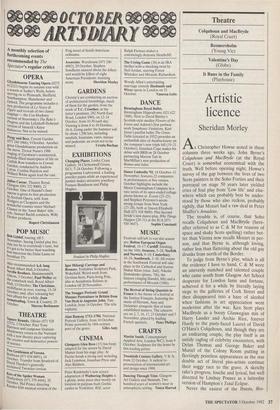

Theatre

Colquhoun and MacBryde (Royal Court) Rosmersholm (Young Vic) Valentine's Day (Globe) It Runs in the Family (Playhouse)

Artistic licence

Sheridan Morley

As Christopher Howse noted in these columns three weeks ago, John Byrne's Colquhoun and MacThyde (at the Royal Court) is somewhat economical with the truth. Well before opening night, Howse's survey of the gap between the lives of two Scots painters in the Soho Forties and their portrayal on stage 50 years later yielded cries of foul play from 'Low life' and else- where which can probably best be under- stood by those who also reckon, probably rightly, that Mozart had a raw deal in Peter Shaffer's Amadeus.

The trouble is, of course, that Soho recalls Colquhoun and MacBryde (here- after referred to as C & M for reasons of space and shaky Scots spelling) rather bet- ter than Vienna now recalls Mozart in per- son, and that Byrne is, although loving, rather less than flattering about the old gay drunks from north of the Border.

To judge from Byrne's play, which is all the evidence I have to hand, C & M were an unevenly matched and talented couple who came south from Glasgow Art School desperate for London fame and fortune, achieved it for a while by literally laying siege to the galleries of Cork Street and then disappeared into a haze of alcohol when fashions in art appreciation went modernist after the war. Ken Stott plays MacBryde as a boozy Glaswegian mix of Harry Lauder and Archie Rice, forever Hardy to the pasty-faced Laurel of David O'Hara's Colquhoun, and though they are an endearing couple, the play itself is an untidy ragbag of celebrity encounters, with Dylan Thomas and George Baker and Muriel of the Colony Room putting in fleetingly pointless appearances as the star double act of literal piss-artists continue their soggy race to the grave. A sketchy rake's progress, louche and lyrical, but well directed by Lindsay Posner as a latterday version of Hampton's Total Eclipse.

Never the easiest of the Ibsens, Ros- mersholm gets a rare revival at the Young Vic by Annie Casteldine, who seems uncer- tain whether she is dealing with a Shavian drawing-room drama about people drown- ing in their own guilt or something rather more Freudian. When it first opened in London in 1893 the Times found its leading characters 'enigmatic and disagreeable, impossible people doing wild things for no apparent reason in contemptible provincial surroundings', and at least Ms Casteldine isn't having any of that.

Her Rosmer and Rebecca West (Corin Redgrave and Francesca Annis) are ele- gant social exiles, locked together by their own guilty passions in a scenario which nowadays would have come from Roman Polanski. Around them, Bernard Lloyd as the disillusioned, doomed liberal rebel and Allan Corduner as the creepily triumphant conservative reactionary outline the bor- ders of the dilemma, but at its centre nei- ther Redgrave nor Annis is quite charismatic enough to take us with them into the gulf of their despair. It is ultimate- ly Miriam Karlin, watching their double suicide as the all-knowing housekeeper, who best captures the evening's mood of tetchy irritability and mutual incomprehen-

sion.

At the Globe, though probably not for much longer, Benny Green and Denis King have a musical, Valentine's Day, of Bernard Shaw's You Never Can Tell which points up the original fragility of the comedy without adding a strong enough score to justify the conversion. This is no My Fair Lady, but then You Never Can Tell is no Pygmalion either; what the show does have is Green's tremendous Shavian expertise as a lyricist, some charmingly tinkly mid-1950s music, and Edward Petherbridge as an ineffable dancing head waiter.

And, finally, great news at the Playhouse, which after some rocky times under Jeffrey Archer and Peter Hall has been converted into a resident base for the farces of Ray Cooney, starting with It Runs in the Family, which has a cast with about 200 years of farcical experience, and that's just Doris Hare. Around her, Cooney has assembled the best comic team in town (John Quayle, Henry McGee, Windsor Davies, Dennis Ramsden et al), with Cooney himself pre- siding as actor, author and director, a man so deeply dedicated to the format that he now even manages to act and look like a mix of Robertson Hare and Ralph Lynn.

Prelude to the Afternoon of a Faun.

Previous page

Previous page