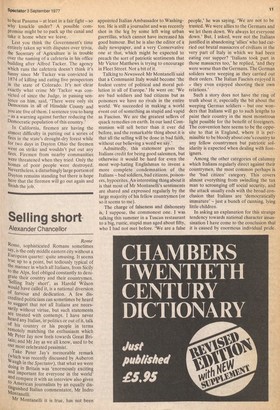

Selling short

Alexander Chancellor

Rome Rome, sophisticated Romans sometimes saY, is the only middle eastern city without a European quarter: quite amusing. It seems true up to a point, but tediously typical of the manner in which all Italians, from Sicily to the Alps, feel obliged constantly to deniFrate their country and their countrymen. Selling Italy short', as Harold Wilson would have called it, is a national diversion of fervour and dedication. A few discredited politicians can sometimes be heard to suggest that not all Italians are necessarily without virtue, but such statements are treated with contempt. I have never heard any Italian, ilT politics or out of it, talk of his country or his people in terms remotely matching the enthusiasm which Mr Peter Jay now feels towards Great Britain; and Mr Jay as we all know, used to be Our most celebrated pessimist. Take Peter Jay's memorable remark (which was recently discussed by Auberon Waugh in the Spectator), that what we were doing in Britain was 'enormously exciting and important for everyone in the world' and compare it with an interview also given tp American journalists by an equally distinguished Italian commentator, Mr Indro Montanelli. Mr Montanelli it is true, has not been appointed Italian Ambassador to Washington. He is still a journalist and was recently shot in the leg by some left wing urban guerrillas, which cannot have increased his good humour. But he is also the editor of a daily newspaper, and a very Conservative one at that, which might be expected to preach the sort of patriotic sentiments that Mr Victor Matthews is trying to encourage in Fleet Street. Not a bit of it.

Talking to Newsweek Mr Montanelli said that a Communist Italy would become 'the foulest centre of political and moral pollution in all of Europe.' He went on: 'We are bad soldiers and bad citizens but as poisoners we have no rivals in the entire world. We succeeded in making a world event out of something as stupid and vapid as Fascism. We are the greatest sellers of quack remedies on earth. In our land Communism will sell better than it ever did before, and the remarkable thing about it is that all the selling will be done in bad faith, without our believing a word we say.'

Admittedly, this statement gives the Italians credit for being good salesmen, but otherwise it would be hard for even the most wop-hating Englishman to invent a more complete condemnation of the Italians — bad soldiers, bad citizens, poisoners, hypocrites. An interesting thing about it is that most of Mr Montanelli's sentiments are shared and expressed regularly by the large majority of his fellow countrymen (or so it seems to me).

The charge of falseness and dishonesty is, I suppose, the commonest one. I was talking this summer in a Tuscan restaurant to a big, rustic, stupid man aged about fifty, who I had not met before. 'We are a false people,' he was saying, 'We are not to be trusted. We were allies to the Germans and we let them down. We always let everyone down.' But, I asked, were not the Italians justified in abandoning 'allies' who had carried out brutal massacres of civilians in the very part of Italy in which we had been eating our supper? 'Italians took part in those massacres too,' he replied, 'and they were worse than the Germans. The German soliders were weeping as they carried out their orders. The Italian Fascists enjoyed it — they even enjoyed shooting their own relations.'

Such a story does not have the ring of truth about it, especially the bit about the weeping German soldiers — but one won-. ders that Italians will go to such lengths to paint their country in the most monstrous light possible for the benefit of foreigners. The convention here seems to be the opposite to that in England, where it is permissible to be bloody about one's country to any fellow countrymen but patriotic solidarity is expected when dealing with foreigners.

Among the other categories of calumny which Italians regularly direct against their countrymen, the most common perhaps is the `bad citizen' category. This covers almost everything from swindling the tax man to scrounging off social security, and the attack usually ends with the broad conclusion that Italians are `democratically immature' — just a bunch of cunning, lying little children.

In asking an explanation for this strange tendency towards national character assassination I have come to the conclusion that it is caused by enormous individual pride. Like everybody else, the Italian wishes to present himself to strangers in the most favourable possible light. Unlike the timid Englishman who will try to increase his own self esteem by extolling the virtues of his race, the Italian will do the opposite: he feels that only by emphasising the enormous gulf — cultural, intellectual and every other sort — that exists between himself and his fellows can he be taken seriously. He knows little about foreigners but imagines that they do not have a very high opinion of Italians — and in this he is usually right.

(Here I cannot resist a digression on the subject of Italians and foreigners. In the Tuscan countryside, where I regularly stay, I was distressed to discover the surprisingly low esteem in which the English people are held. Since the war, we have had a reputation as pillagers and rapers of young women, and our behaviour is compared unfavourably with the `correctness' of the Germans. I could imagine British soldiers leaving behind them a disgusting mess and perhaps using a Michaelangelo painting as a dart board, but rape on a large scale seemed unlikely. Only subsequently did I discover that those whom the people were calling 'English' were in fact Moroccans. The Moroccans were the first allied troops to 'liberate' Tuscany and did duty in a very old fashioned manner. It says something about the mutual understanding of the peoples of Europe that Italian peasants, however isolated, could seriously have thought that a hoard of dark brown Moroccans were English.) Italians themselves have great individual • pride, but almost no national pride. They believe that the Italian nation as a whole is a failure, so they deal elegantly with this problem by declaring quite simply that the Italian nation does not exist. To foreigners, Italians appear remarkably similar, they speak the same language, eat the same food, drive at the same speed, wear the same type of clothes and are generally of darker complexion than the average Swede. But no. According to ordinary Italians, they speak different languages in every region and food is completely different everywhere. Everything, in fact, is so utterly different that only a fool could mistake the Italians for one people.

I don't agree with any of this. If I were an Italian, I would be a patriot. One of the endearing things about them is that they imagine, in their simplicity, that almost all other countries, and particularly England, are governed by incorruptible institutions revered by the mass of the citizenry, who would sooner lose their right arms than endanger for one second the sovereignty of Parliament. The Italians do not realise the strength they have acquired from their deep-rooted cynicism.

In the end, the Italian expects nothing from the state: he knows he must rely on his own industry, his own cunning (or some kind of dishonesty) and the supplement of his family and friends if he is to survive and prosper. His prosperity is so recently acquired that he is not frightened of losing it. Even in relative poverty he eats and strives with some success to enjoy himself. He does not require a `Silver Jubilee' to persuade him to converse with his neighbours. Meanwhile the Italian state is not as incompetent as that in carrying out its responsibilities. Many parts of the countryside may have been bespoiled, but to an Englishman it seems almost a miracle that the centres of the old cities have been so well preserved and are still so full of vitality. Regional devolution has been implemented here, and it seems successfully, though few British politicians care to study the Italian example. The Communist menance may or may not be successfully contained, but the attempts to achieve this objective are both cunning and original. Apparently they are more threatening than our own, but the Italians are still coping quite cheerfully. How? I don't know, but certainly what they are doing is at best as 'enormOusly exciting and important for everyone in the world' as anything going on in Great Britain.

Previous page

Previous page