Coup de grace

ROBERT BIRLEY

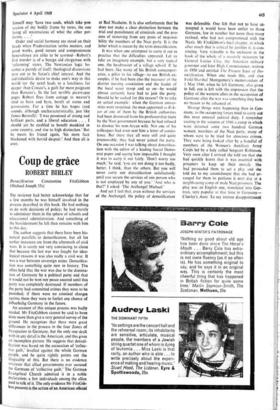

Denazification Constantine FitzGibbon

(Michael Joseph 35s)

The reviewer had .better acknowledge that for a few months he was himself involved in the process described in this book. He had nothing to do with decisions of policy; he had merely to administer them in the sphere of schools and educational administration. And something of the bewilderment he felt then remains with him to this day.

The author suggests that there have been his- torical parallels, to denazification, but all his earlier instances are from the aftermath of civil wars. It is surely not very convincing to claim that because the last war was fought for ideo- logical reasons it was also really a civil war. It was a war between sovereign states. Denazifica- tion was something quite new in history. The allies held that the war was due to the domina- tion of Germany by a political party and that it would not be won nor peace assured until this party was completely destroyed. If members of the party had committed crimes they were to be punished; if there were no criminal charges against them they were to forfeit any chance of influellcifig Germany in the future.

An account of this unique process was badly needed. Mr FitzGibbon cannot be said to have done more than give a very general survey of the ground. He recognises that there were great differences in the process in the four Zones of Occupation in Germany, but the only one dealt with in any detail is the American, and this gives an incomplete picture. He suggests that denazi- fication was based on the accusation of 'collec- tive guilt,' levelled against the whole German People, and he quite rightly points out the illogicality of this. But there is no evidence whatever that allied governments ever accused the Germans of 'collective guilt.' The German Evangelical Church admitted it in a noble declaration; a few individuals among the allies used to talk of it. The only evidence Mr FitzGib- bon presents is the action of an American official

at Bad Nauheim. It is also unfortunate that he does not make a clear distinction between the trial and punishment of criminals and the pro- cess of removing from any posts of responsi- bility the members of the Nazi party. It is the latter which is meant by the term denazification.

It was when one attempted to carry it out in practice that the difficulties appeared. Let us take an imaginary example, but a very typical one, the headmaster of a village school. If he had been, like many of his British contempor- aries, a pillar in his village—to use British ex- amples. if he had been also the treasurer of the district nursing association and the leader of the local scout troop and so on—he would almost certainly have had to join the party. Should he be sacked for this reason? Or to take an actual example: when the German univer- sities were reopened, the man appointed as Rek- tor of one of them by the British authorities had been dismissed from his professorship there by the Nazi governmeni because he had refused to divorce his non-Aryan wife. Not one of his colleagues had even sent him a letter of condo- lence. But there they all were still and quite irremovable; they had never joined the party. On one occasion I was talking about denazifica- tion with the editor of a leading Social Demo- crat paper and saying how impossible I thought it was to carry it out fairly. 'Don't worry too much,' he said, 'you are not doing it too badly, better. I think, than the others. But you will never carry out denazification satisfactorily until you secure the services of one person who is not employed by any of you.' And who is that?' I asked. 'The Archangel Michael.'

And yet I feel that, even without the services of the Archangel, the policy of denazification was defensible. One felt that not to have at- tempted it would have been unfair to those Germans, few in number but more than many realised, who had not compromised with the Nazis. Mr FitzGibbon's final chapter, in which after much that is critical he justifies it, is con-

vincing. Very valuable is his inclusion in the book of the whole of a masterly statement by General Lucius Clay. the American military governor and later High Commissioner, written in 1950 and entitled The Present Slate of De- nazification. When one reads this, and also Field-Marshal Montgomery's memorandum of I May 1946, when he left Germany, also given in full, one is left with the impression that the policy of the western allies in the occupation of Germany after the war was something they have no 'feason to be ashamed of.

Strange things were happening then in Ger- many, as the occupying forces tried to carry out this most unusual judicial duty. I remember visiting in the autumn of 1946 a camp in which were detained some two hundred German women, members of the Nazi party, many of whom were to be tried for atrocious crimes. They were being looked after by a handful of members of the Women's Auxiliary Army Cords led by a lady called Sergeant Robinson.' Very soon after I arrived she told me that she had quickly learnt that it was essential with prisoners to keep up their morale. She had-persuaded them to act a play and she told me to my astonishment that she had ar- ranged for them to perform it next day at a neighbouring camp of male Nazi prisoners. The play was an English one, translated into Ger- man, Very popular at that time in Germany-r- Charley's Aunt. To my intense disappointment I had an inescapable engagement elsewhere and I could not see the production. It is in any case hardly possible to imagine Charley's Aunt acted by an all-female cast, quite impossible to imagine it being acted by a cast of Nazi women. It was a strange way to finish off a war. But there have been worse ways of doing it.

Previous page

Previous page