HAVE SOAP-BOX, WILL TRAVEL

John Simpson sticks close to John Major, as the Prime Minister attempts to shake off the dead hand of Conservative Central Office

'OPEN quotes I can't understand what all the complaints are about over the NHS comma close quotes said Alison comma a patient at the hospital point par.'

`The last time we had a crowd like this here was in 1976, I think it was — when was it the Queen came to Cupar, Mary?'

'Major, Major, Major, Out, Out, Out.'

'It was really lovely to meet him, but I couldn't vote Conservative in the Rhond- da. My children would say I was a traitor.'

'If only I could shake his hand. Do you think he'll see me over here? He does look nice, doesn't he? Perhaps I ought to vote for him after all.'

'After what he's done to my business, him and his friends, I don't think I'll be saying hello to him, thank you very much.'

'Open quotes we could all die if Neil Kin- nock got in comma close quotes she said point par.'

It is something of a relief to find, as we travel around the country with John Major, the tabloid journalists among us fil- ing their daily quota of undiluted praise for him and his party, that the people of Britain remain as placid, as balanced, as quietly ironical, as tolerant, as they always have been; no doubt they are just as keen to touch their forelock to the great as they always have been, too. By the time Mr Major's blue campaign coach eases its way through the narrow streets of another small town a sizable crowd has usually gathered. There is a certain amount of booing and rather more cheering.

For a man regarded as being short on charisma, he attracts a great deal of inter- est; and when the camera crews envelop him and people thrust out their hands towards him as though he has healing in his touch, there is enough excitement to make us wonder whether he really is quite as short of charisma as most of us have assumed. The occasional egg is thrown in the traditional fashion. But Mr Major does not stir the extremes of emotion as Mrs Thatcher did, and so even in places where the Socialist Workers' Party has gathered to give him a hard time — how do they know where he is going to be with such accuracy? — there is never anything more than verbal abuse.

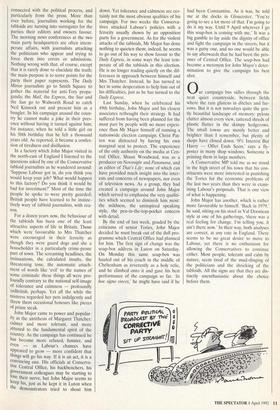

In Luton last weekend, for instance, where he mounted his soap-box and orat- ed inaudibly at the barrackers through a megaphone, there was no actual violence. Sometimes the unworthy thought comes to mind that if he took a bottle on the head and a trickle of blood were to run deco- rously down those mild features, it would be worth at least ten marginals to him. But 'A slob to the end: he wanted his ashes to be flicked onto the carpet.' the enrages have so far resolutely refused to co-operate. A Young Conservative steward wiped yolk out of his eye and off the shoul- der of his Cambridge blue sweat-shirt in George Street, Luton, but nothing hit the man on the soap-box; and apart from the. eggs the only things that flew were screwed-up election leaflets.

Soon the insidious party spin-doctors were on the telephone. Conservative Cen- tral Office rang to identify a woman, a local Labour supporter, as the organiser of the demonstration; they are anxious in Smith Square to associate any extremism with Labour. Walworth Road rang to let us know that the Luton police thought it had mostly been good-natured, as though we were incapable of speaking to the Luton police ourselves. The faint suspicion remained that Mr Major had deliberately charged into a hostile group and stirred them up, in order to breathe life into his hitherto dull campaign and to present Labour as the party of street violence. 'Mob rule,' a Tory from the constituency called it; I have seen worse mob rule around the bar at the annual lunch of the French Farmers' Association.

There was a voice at my elbow. 'You're just a tool of the Tory government, telling people no one got killed in all that bomb- ing in Iraq. And then you got your reward, didn't you?' The speaker was a thin-faced, Cassius-like figure in an anorak with a badge on the lapel that read 'Robin Hood Was A Socialist: Vote Labour.' You did it all just for a medal on a ribbon. They didn't even have to pay you.' The words were hos- tile but the tone was ironic, and instead of stalking away I stayed and debated with him, his brother and his friend: all SWP stalwarts. They had a jaunty air to them, as though Dickens had foreseen Trotskyists, and written them into Sketches by Boz.

No doubt they hated Neil Kinnock with a vengeance, but they advocated voting Labour all the same in order to get the Conservatives out. I gave them my line on the Gulf war, then said there was one big difference between them and me: I didn't believe that any political theology, from Thatcherism to Trotskyism via social democracy, could have all the answers all the time to all our national problems. 'Wrong,' said Cassius, fingering the knap on my overcoat; 'there's two differences between us. I'm skint and you're not.' It was a good exit line, and he shook my hand with warmth and self-pleasure. I saw him later in the demonstration, waving his clenched fist at John Major and yelling, 'Tory scum'; he winked when he caught my eye.

In spite of the recession, in spite of the refutation of the supposed miracle of the 1980s, in spite of the collapse of a thousand small businesses a week, there seems to be less real anger on the streets in this elec- tion than there was in 1987. There is, how- ever, a distinct nastiness around, but it comes less from the voters than from those

connected with the political process, and particularly from the press. More than ever before, journalists working for the tabloids are turning into surrogates for the parties their editors and owners favour. The morning news conferences at the two main party headquarters are often intem- perate affairs, with journalists attacking the politicians who appear and trying to force them into errors or admissions. Nothing wrong with that, of course, except that it is rarely done to elucidate the truth; the main purpose is to score points for the party their paper represents. The Daily Mirror journalists go to Smith Square to gather the material for anti-Tory propa- ganda; the Mail, the Express, the Star and the Sun go to Walworth Road to catch Neil Kinnock out and present him as a bungler. In his campaign around the coun- try he cannot make a joke in their pres- ence without having it turned against him; for instance, when he told a little girl on his 50th birthday that he felt a thousand years old. As reported, it became a confes- sion of tiredness and disillusion.

In a factory which John Major visited in the north-east of England I listened to the questions asked by one of the Conservative tabloid journalists as he wandered around: `Suppose Labour got in, do you think you would keep your job? What would happen to this factory? Do you think it would be bad for investment?' Most of the time the people he spoke to were pretty guarded; British people have learned to be instinc- tively wary of tabloid journalists, with rea- son.

For a dozen years now, the behaviour of the tabloids has been one of the least attractive aspects of life in Britain. Those which were favourable to Mrs Thatcher were encouraged in their ferocity as though they were guard dogs and she a householder in a particularly crime-prone part of town. The screaming headlines, the insinuations, the calculated insults, the threatening tone, the automatic attach- ment of words like `evil' to the names of some criminals: these things all were pro- foundly contrary to the national self-image of tolerance and calmness — profoundly unBritish, perhaps. Yet all the while the mistress regarded her pets indulgently and threw them occasional honours like pieces of prime steak.

John Major came to power and popular- ity as the antithesis of Margaret Thatcher: calmer and more tolerant, and more attuned to the fundamental spirit of the Country. As the campaign has continued he has become more relaxed, funnier, and even — as Labour's chances have appeared to grow — more confident that things will go his way. If it is an act, it is a convincing one. His officials at Conserva- tive Central Office, his backbenchers, his government colleagues may be starting to lose their nerve, but John Major seems to keep his, just as he kept it in Luton when the demonstrators tried to shout him

down. Yet tolerance and calmness are cer- tainly not the most obvious qualities of his campaign. For two weeks the Conserva- tives attacked Labour's policies with a ferocity usually shown by an opposition party for a government. As for the violent attacks of the tabloids, Mr Major has done nothing to quieten them; indeed, he seems to go out of his way to show favour to the Daily Express, in some ways the least tem- perate of all the tabloids in this election. He is no longer trading quietly on the dif- ferences in approach between himself and Mrs Thatcher. Instead, he has turned to her in some desperation to help him out of his difficulties, just as he has turned to the Daily Express.

Last Sunday, when he celebrated his 49th birthday, John Major and his closest associates rethought their strategy. It had suffered from having been planned for the most part by people with no more experi- ence than Mr Major himself of running a nationwide election campaign. Christ Pat- ten was distracted by having his own marginal seat to protect. The experience of the only authority on the media at Cen- tral Office, Shaun Woodward, was as a producer on Newsnight and Panorama, and as editor of That's Life; none of which can have provided much insight into the inter- ests and concerns of newspapers, nor even of television news. As a group, they had created a campaign around John Major which served to emphasise the very qualiti- ties which seemed to diminish him most: the mildness, the uninspired speaking style, the pen-in-the-top-pocket concern with detail.

By the end of last week, goaded by the criticisms of senior Tories, John Major decided he must break out of the dull pro- gramme which Central Office had planned for him. The first sign of change was the soap-box address in Luton on Saturday. On Monday this same soap-box was hauled out of his coach in the middle of Cheltenham as reverently as a holy relic, and he climbed onto it and gave his best performance of the campaign so far. 'In hoc signo vinces,' he might have said if he

had been Constantine. As it was, he told me at the docks in Gloucester, 'You're going to see a lot more of that. I'm going to do it my way. Until 9 April wherever I go this soap-box is coming with me.' It was a big gamble to lay aside the dignity of office and fight the campaign in the streets, but it was a gutsy one, and no one would be able to say afterwards that he had been the pris- oner of Central Office. The soap-box had become a metonym for John Major's deter- mination to give the campaign his best shot.

Our campaign bus sidles through the neat quiet countryside, between fields where the rain glistens in ditches and fur- rows. But it is not nowadays quite the gen- tly beautiful landscape of memory: pylons clutter almost every view, tattered shreds of plastic flutter in the skimpy hedgerows. The small towns are mostly better and brighter than I remember, but plenty of shops have closed down. '0% Interest But Hurry — Offer Ends Soon,' says a fly- poster in many shop windows. Someone is printing them in large numbers.

A Conservative MP told me as we stood in the high street of his town that his con- stituents were more interested in punishing the Tories for the economic problems of the last two years than they were in exam- ining Labour's proposals. That is one view of what is happening.

John Major has another, which is rather more favourable to himself. 'Back in 1979,' he said, sitting on his stool in Val Doonican style at one of his gatherings, `there was a real feeling for change. I'm telling you, it ain't there now.' In their way, both analyses are correct, at any rate in England. There seems to he no great desire to move to Labour, yet there is no enthusiasm for allowing the Conservatives to continue either. Most people, toletant and calm by nature, seem tired of the mud-slinging of the politicians and the shrieking of the tabloids. All the signs are that they are dis- tinctly unenthusiastic about the choice before them.

Previous page

Previous page