THE HEREDITARY PRINCIPLE

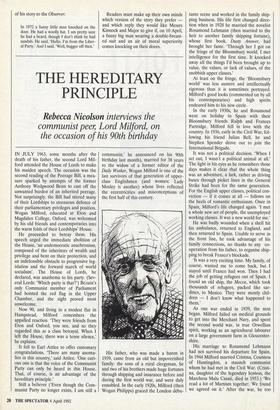

Rebecca Nicolson interviews the

communist peer, Lord Milford, on the occasion of his 90th birthday

IN JULY 1963, some months after the death of his father, the second Lord Mil- ford attended the House of Lords to make his maiden speech. The occasion was the second reading of the Peerage Bill, a mea- sure sparked by attempts of the former Anthony Wedgwood Benn to cast off the unwanted burden of an inherited peerage. Not surprisingly, the Bill had stirred many of their Lordships to strenuous defence of their parliamentary privileges and position. Wogan Milford, educated at Eton and Magdalen College, Oxford, was welcomed by his old friends and contemporaries into the warm folds of their Lordships' House.

He proceeded to betray them. His speech urged the immediate abolition of the House, 'an undemocratic anachronism, composed of the inheritors of wealth and privilege and bent on their protection, and an indefensible obstacle to progressive leg- islation and the forward march of world socialism'. The House of Lords, he declared, was anathema to his party. (Sev- eral Lords: 'Which party is that?') Br;tain's only Communist member of Parliament had hoisted the red flag in the Upper Chamber, and the sight proved most unwelcome.

Now 90, and living in a modest flat in Hampstead, Milford remembers the appalled reaction. 'They were friends from Eton and Oxford, you see, and so they regarded this as a class betrayal. When I left the House, there was a tense silence,' he explains.

It fell to Earl Attlee to offer customary congratulations. 'There are many anoma- lies in this country,' said Attlee. 'One curi- ous one is that the voice of the Communist Party can only be heard in this House. That, of course, is an advantage of the hereditary principle.'

Still a believer (`Even though the Com- munist Party no longer exists, I am still a communist,' he announced on his 90th birthday last month), married for 38 years to the widow of a former editor of the Daily Worker, Wogan Milford is one of the last survivors of that generation of upper- class Englishmen (and women: Lady Mosley is another) whose lives reflected the eccentricities and misconceptions of the first half of this century.

His father, who was made a baron in 1939, came from an old but impoverished family: the sons of a rural clergyman, he and two of his brothers made huge fortunes through shipping and insurance before and during the first world war, and were duly ennobled. In the early 1920s, Milford (then Wogan Philipps) graced the London débu-

tante scene and worked in the family ship- ping business. His life first changed direc- tion when in 1928 he married the novelist Rosamond Lehmann (then married to the heir to another family shipping fortune), whose first book, Dusty Answer, had brought her fame. 'Through her I got on the fringe of the Bloomsbury world. I met intelligence for the first time. It knocked away all the things I'd been brought up to value, the values, or lack of values, of the snobbish upper classes.'

At least on the fringe, the 'Bloomsbury world' was less austere and intellectually rigorous than it is sometimes portrayed. Milford's good looks (commented on by all his contemporaries) and high spirits endeared him to his new circle.

In the early 1930s, he and Rosamond went on holiday to Spain with their Bloomsbury friends Ralph and Frances Partridge. Milford fell in love with the country. In 1936, early in the Civil War, fol- lowing his friend Julian Bell, he and Stephen Spender drove out to join the International Brigade.

It was not a political decision. 'When I set out, I wasn't a political animal at all.' The light in his eyes as he remembers those days makes it clear that the whole thing was an adventure, a lark, rather as driving buses through picket lines in the General Strike had been for the same generation. For the English upper classes, political con- viction — if it comes at all — follows on the heels of romantic enthusiasm. Once in Spain, Milford's life changed again. 'I met a whole new set of people, the unemployed working classes. It was a new world for me.'

He was badly wounded when a shell hit his ambulance, returned to England, and then returned to Spain. Unable to serve in the front line, he took advantage of his family connections, no thanks to any co- operation from his father, to organise ship- ping to break Franco's blockade.

`It was a very exciting time. My family, of course, wanted me to come back, but I stayed until Franco had won. Then I had the job of getting refugees out of Spain. I found an old ship, the Mecca, which took thousands of refugees, packed like sar- dines, to Mexico. They were mostly chil- dren — I don't know what happened to them.'

As one war ended in 1939, the next began. Milford failed on medical grounds to get into the Merchant Navy, and spent the second world war, in true Orwellian spirit, working as an agricultural labourer on a large government farm in Gloucester- shire.

His marriage to Rosamond Lehmann had not survived his departure for Spain. In 1944 Milford married Cristina, Countess of Huntingdon, a staunch communist whom he had met in the Civil War. (Cristi- na, daughter of the legendary hostess, the Marchesa Malu Casati, died in 1953.) 'We read a lot of Marxism together. We found we agreed on it.' After the war, he too

became a member of the Party. 'My father wrote to me and said, "Any. child of mine who joins the Communist Party will not get a penny." I never really spoke to my father after that.' On the first Lord Mil- ford's death in 1962, his son was indeed left nothing.

The decades after the war were spent farming CI introduced artificial insemina- tion to Gloucestershire'), painting and spreading the word. Milford's entry in Who's Who summarises his political career:

Former member of Henley on Thames RDC; Communist Councillor, Cirencester RDC, 1946-49; has taken active part in building up National Union of Agricultural Workers in Gloucestershire and served on its county committee. Prospective Party can- didate (Labour), Henley on Thames, 1938- 39; contested (Con) Cirencester and Tewkesbury, 1950.

'I lost my deposit — oh God, yes!' He polled 423 votes, less than 1 per cent of the votes cast, in the constituency later repre- sented by Nicholas Ridley.

Ridley is Milford's godson. Woodrow Wyatt was his stepson-in-law, although Wyatt's early socialist commitments were rather more short-lived than those of his single-minded stepfather-in-law. Family lore has it that when Nicholas Ridley was standing for parliament in Cirencester and Tewkesbury, Ridley's agent rang him to say that his godfather, Wogan Milford, was standing against him in the Communist interest. 'Oh good, that'll split the Labour vote,' was Ridley's response. When eventu- ally Ridley asked Milford if this really was the case, Milford said, 'I'll stand if you lend me the £150 deposit.'

His former son-in-law, P.J. Kavanagh, recalls how at political meetings Milford would be 'chased by agricultural students, who would suddenly haul up and say, "Hang on chaps, he's a gentleman!" And during the war his telephone was bugged, and he would occasionally get so fed up he would say, "Oh come on, constable, get off the line," to which the constable would reply, "Sorry, Sir."' Kavanagh also describes how occasion- ally delegations from the Soviet Union would come down to the farm at weekends to shoot with the communist peer. 'They would all stand round a rabbit hole. As Wogan said, if a rabbit had ever appeared, the comrades would all have shot each other.'

Less charmingly English are the pas- sions which this most courteous and well- mannered man seems to arouse in his political opponents. After his maiden speech, Milford was largely ostracised in the House of Lords, even though for many years he spoke for his party at least twice a week ('on Vietnam, on Nicaragua, on the abolition of the House of Lords'). On the Rural District Council, feelings ran even higher. 'They were all Tories except me, and in the meetings notes were passed round about me, things like "Doesn't he stink!" They were all very rude — I was rather proud of fighting them.' He lost his seat in 1949 by 14 votes. 'The Tories mobilised every vote they could. They didn't just get people out of hospital, they organised a smear campaign. "We'll never allow Colesbourne to become another Hungary," they said.'

The extraordinary thing is that his oppo- nents were so blinded by his communist label that they failed to see that Lord Mil- ford would never have allowed it either. He is much too English, too much a product of his own background, for anything like that. Stalin 'became an enemy when the truth emerged'.

His two visits to the Soviet Union left him 'very disappointed. I went to look at their farming. It was very bad. No one knew about agriculture.' These days he feels keenly that communism as put into practice has failed. 'The problem is ethnic.' Their Lordships need not have worried about the Red in their midst: at the end of the day, as the agricultural students of Cirencester realised, a gentleman is a gen- tleman. That, of course, is an advantage of the hereditary principle.

Rebecca Nicolson is features editor of the Observer

Previous page

Previous page