Exhibitions 1

Caravaggio (Palazzo Ruspoli, Rome, till 2 May)

True to a dramatic life

Roderick Conway Morris

In May 1606 Caravaggio fled from Rome having killed an opponent in an argument over a tennis match. This was the culmina- tion of several years of hooliganism, during which he was regularly hauled before the courts for assault and battery, brawling, throwing stones at the police, vandalism and, on one occasion, hitting a waiter in the face with a plate of artichokes. That the artist had not already been imprisoned for more than short stretches was thanks only to his powerful ecclesiastical patrons. But this time the verdict was 'capital banish- ment' — an open invitation to any state that laid hands on him to carry out the death sentence.

The drama of Caravaggio's life is amply reflected in his works, with their startling contrasts of dazzling light and tenebrous gloom; their freezing of fleeting moments of violence, tension, surprise and eerie calm; their depiction of a whole gamut of emotions from fear and horror to resigna- tion and devotion.

Caravaggio invented realism more or less singlehandedly, revolutionising 17th-

century painting and profoundly affecting both Rembrandt and Rubens. His was a heightened realism, however, in which the central figures are rendered totally con- vincingly down to the last detail of flesh tone and dress, as are the key props books, playing cards, musical instruments, fruit — but with every other extraneous element excluded. His backgrounds are ruthlessly stripped down so as not to detract from the drama: either being so dark as to be well-nigh impenetrable or so bright as to be bleached of features. For Caravaggio an elaborate backdrop consists of a dimly-discerned curtain, a plastered interior wall, some shadowy foliage.

How Caravaggio painted, how his style developed during his hectic life, are the subjects of this exhibition, subtitled 'How his masterpieces were made' and organised by Professor Mina Gregori of the Roberto Longhi Foundation in Florence to mark the centenary of its eponymous founder, who was primarily responsible for the rediscovery of Caravaggio's genius. There are a score of paintings in the show, and numerous others to be viewed in Rome's churches and galleries with the fresh insights it provides.

Forced to leave northern Italy after a serious scrape with the law before he was 20, Caravaggio made his way to Rome in 1592. Following a gruelling period of poverty, during which he maintained an absolute dedication to his artistic vocation, he won the attention of Cardinal Del Monte, the Grand Duke of Tuscany's ambassador in Rome.

The Medicis' Palazzo Madama, where the cardinal lived and Caravaggio found a new home, is variously reputed to have been a riotous transvestite and homosexual playground and the perfectly dignified resi-

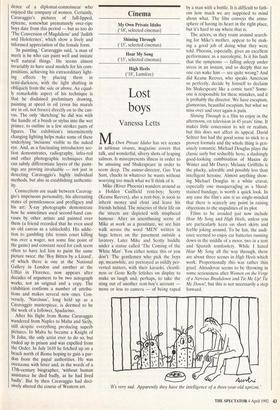

'Christ Crowned with Thorns', by Caravaggio, from the Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna dence of a diplomat-connoisseur who enjoyed the• company of women. Certainly, Caravaggio's pictures of full-lipped, epicene, somewhat prematurely over-ripe boys date from this period — but so too do 'The Conversion of Magdalene' and 'Judith and Holofernes', which show a lively and informed appreciation of the female form.

'In painting,' Caravaggio said, 'a man of merit is he who can paint well and imitate well natural things.' He seems almost invariably to have used models for his com- positions, achieving his extraordinary light- ing effects by placing them in semi-darkness, with the light shafting in obliquely from the side or above. Au equal- ly remarkable aspect of his technique is that he disdained preliminary drawing, painting at speed in oil (even his murals are in oil, not fresco) directly on to the can- vas. The only 'sketching' he did was with the handle of a brush or stylus into the wet primer, to outline in a few strokes parts of figures. The exhibition's intermittently changing lighting helps make some of these underlying 'incisions' visible to the naked eye. And, as a fascinating introductory sec- tion demonstrates, radiography, infra-red and other photographic techniques that can subtly differentiate layers of the paint- ings are proving invaluable — not just in detecting Caravaggio's highly individual methods, but also in establishing authentic- ity.

Connections are made between Caravag- gio's impetuous personality, his alternating states of pennilessness and profligacy and his art: X-ray photographs demonstrate how he sometimes used second-hand can- vases by other artists and painted over them (a friend recorded that he even used an old canvas as a tablecloth). His addic- tion to gambling (the tennis court killing was over a wager, not some fine point of the game) and constant need for cash seem often to have led him to paint the same picture twice: the 'Boy Bitten by a Lizard', of which there is one at the National Gallery in London and another at the Uffizi in Florence, now appears after decades of argument to be two autograph works, not an original and a copy. The exhibition confirms a number of attribu- tions and makes several new ones. Con- versely, 'Narcissus', long held up as a Caravaggio masterpiece, is deemed to be the work of a follower, Spadarino.

After his flight from Rome Caravaggio wandered from Naples to Malta and Sicily, still despite everything producing supeib pictures. In Malta he became a Knight of St John, the only artist ever to do so, but ended up in prison and was expelled from the Order. In July 1610 he fetched up on a beach north of Rome hoping to gain a par- don from the papal authorities. He was

overcome with fever and, in the words of a 17th-century biographer, 'without human assistance he died badly, as he had lived badly'. But by then Caravaggio had deci- sively altered the course of Western art.

Previous page

Previous page