Will Japan return to its past?

Murray Sayle

Tokyo Two soggy Sundays ago a macabre ceremony took place. all but unnoticed by the Japanese press, in the nondescript Tokyo

district called Ikebukuro. In any other country, there would have been massive media coverage. Japan, as if avoiding an embarrassing family secret, pointedly looked away. For many Japanese, the past is not simply forgotten. It never happened.

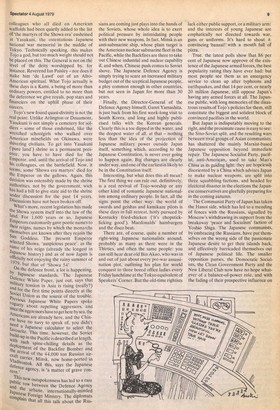

Ikebukero (`Ikky Buckeroo' to the deep-drinking, hard-playing GIs of the American occupation) is neither city nor suburb. The town terminus, like Victoria or Paddington, of a net of suburban railway lines. Ikebukero handles 2.4 million passengers a day, and around the station has grown up a seedy neon-lit wilderness of bars. strip joints and public bath houses. dominated by one immense building: the 60-storey glass and marble tower of Sunshine City, the biggest building in Asia, gleaming and bright and new, intended to be the nucleus of yet another district devoted to Japan's booming international business, Sunshine City stands, for Japan, in unusually spacious grounds. swept almost bare of the remnants of the past. The site came available for redevelopment by a lucky chance — in 1966 Tokyo Municipality decided to demolish the grim old Sugamo Prison, of painful memories for Japanese, where Japanese 'thought criminals' were held during the Second World War. and Japanese war criminals were held for trial and execution by the Allies after the war was over.

A small part of Sugamo was left standing. and stands to this day. From the gourmet restaurant on top of Sunshine City you look down on a rectangle, tiny from this height. of weathered cement walls made of grey volcanic sand, its single entrance a rusty iron door which swings on stiff, groaning hinges. Inside is a courtyard of bare earth beaten by summer rain against the trunks of a small grove of trees, trim and tortured in the formal. Japanese manner. Five mounds stand close to one of the walls. on which you can still see the crude shutterimarks left by its makers. and in front of the mounds incense climbs in five grieving spirals.

Passing through the iron door, we have stepped back 40 years,: from today's Japan, affluent. peaceable, soaring on ingenious technological wings. to the harsh and arrogant Japan which made war on China, and then on Asia, and then on the world. An appropriate place for such a thought, too: the five mounds mark where gallows once stood, and here, under bright floodlights, at half-past one in the morning of Christmas Eve, 1949, General Hideki Tojo. Japan's wartime Prime Minister, and three of his military colleagues went stiffly and unemotionally to their deaths like Samurai, a last tanzai!' for the Emperor and Japan on their lips. The courtyard of Sugamo Prison is now, officially, holy ground.

This month's ceremony was to consecrate the place of Tojo's punishment, first in a Shinto ceremony. then a Buddhist. Salt (for purity) was scattered, incense lit, the Lotus Sutra intoned. By Japanese ideas, holy ground can never be deconsecrated — the dark courtyard and its memories will rebuke the Sunshine City with its jolly crowds of affluent shoppers and trippers until, some distant day, Japan sinks into the sea.

What's going on here? you may well be wondering. For a rough and ready analogy, Westerners are often tempted to turn to Germany. The apotheosis of Adolf Hitler, the consecration of his terminal bunker as a place of worship would, if reported tomorrow, cause a prickly sensation to run up and down a lot of necks. The cases are not, of course, too closely comparable — Tojo was not, for one thing, a dog-lover — but then again, they are not all that wildly dissimilar, either.

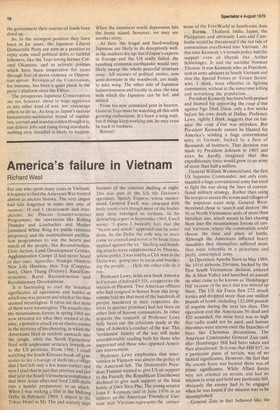

A veteran of the 1905 war with Russia (with a small moustache, but he served as a lieutenant, not a corporal) Tojo's first big job was to head the Kempei Tai, the Oriental version of the Gestapo. in the Japanese puppet state of Manchukuo in the Thirties. As War Minister, Tojo drew up the military field code which specifically denied the status of prisoner-of-war to either Japanese or foreign captives. Appointed Prime Minister in 1941, in a last desperate attempt to resolve the seemingly endless war in China, the alleged encirclement of Japan by the ABCD powers (American. British, Chinese and Dutch) and the very real American sanctions which had cut off Japan's oil supplies. Tajo opted, as military men often do, for a military solution, which brought us Pearl Harbour, Singapore, Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and the deaths of at least 10 million people. including two and a half million Japanese. While Tojo and his colleagues did not bring this gigantic disaster about single-handed, and his conviction for 'waging aggressive war, crimes against peace and crimes against humanity' now sounds somewhat tinny and propagandistic, clearly he was no innocent bystander, either. Most Japanese. one would think, would prefer to forget that Hideki Tojo ever existed.

Most of them do. The turn-out for the consecration ceremony was thin: a Shinto priest, a Buddhist nun, two foreign reporters. some 30 people, a nondescript group of ordinary-looking Japanese. No gang of Rightists in military uniforms, a common sight in other parts of Tokyo, raising thunderous shouts of ibanzair, no bands of helmeted left-wing radicals laying into them with steel pipes. No representative of the government, the Emperor Tojo once served, or the Army which he formerly commanded. Indeed, the presence of women and young children, the familiar bottles of sake and rice cakes spread out on mats all suggested a normal Japanese family remembrance for the dead, and indeed nearly 1,000 Japanese were justly or unjustly hanged for war crimes in the early years of the US occupation.

The ceremony was officially sponsored by something called the Society to Remember the Victims of War Crimes' Trials, not a very well-known or active body. Handing out visiting cards, I got one back from, for example, a Mr Tetsuzo Okamoto from Nagoya, chairman of a group working to recover the Northern Islands (seized from Japan by the Soviets in the last days of World War Two.) Okamoto, about 70 years of age, turned out to be a retired military man with the black-andwhite patriotism such people commonly hold. Even if he is a romantic right-winger, it doesn't matter much.

However, things like the Tojo remembrance don't just happen anywhere, and espe cially not in Japan. The chairman of the Sunshine City, Satoshi Isozaki, is a former head of the Japan National Railways. and the owners of the complex (and thus of the courtyard) are a spread of some of the famous Japanese companies who manufac tured your camera, your television and your motor car. Nothing in Japanese tradition requires the consecration of a place of execution. The Japanese establishment may not have gone as far as formally deciding to rehabilitate General Tojo, but somebody way up there obviously said okay.

We should see the Tojo renaissance against the background of a whole string of events which have taken place this year, none of them earth-shaking in themselves, but, equally, all of them utterly unthinkable in the Japanese political climate of only a year or so back. First, the Japanese and American military commands here have been having their first serious talks about co-operation and eventual joint command, although the mutual security treaty which calls for just such collaboration has been in existence for more than a quarter-century. The talks are going slowly —the US navy has only one officer who can speak Japanese with a working knowledge of his opposite numbers' organisation, the Japanese navy has precious few who can speak English, and the US and Japanese armies have such wildly different traditions, systems and weapons that, as one officer told me, It's like the Green Berets planning to fight shoulder to shoulder with the Vietcong,' Still, the talks are, as they say, pleasantly ongoing. Then, on 18 April last, it was announced that the names of the same Tojo and 13 colleagues who all died on American scaffolds had been quietly added to the list of 'the martyrs of the Showa era' enshrined at Yasukuni, the ostentatious Japanese national war memorial in the middle of Tokyo. Technically speaking. this makes Tojo a god, but too much weight should not be placed on this. The General is not on the level of the deity worshipped by, for instance, Reverend Ian Paisley — nor does it make him 'de Lawd' out of an AfroAmerican spiritual. What Tojo actually is these days is a Kami, a being of more than ordinary powers. entitled to no more than the deference we give royals, pop stars and financiers on the uphill phase of their careers.

Tojo's new found quasi-divinity is not the . real point. Unlike Arlington or Douamont. Yasukuni is not simply a cemetery for soldiers — some of those enshrined, like the wretched schoolgirls who walked over American minefields on Okinawa, were Shivering civilians. To get into Yasukuni (pure land') shrine as a permanent presence, you have to have died for the Emperor, and, until the arrival of Tojo and his colleagues, on the battlefield. Now, it seems, some `Showa era martyrs' died for the Emperor on the gallows. Again, this decision was ostensibly made by the shrine authorities, not by the government, wich has had a bill to give state aid to the shrine under discussion for the past 14 years. Discussions have not been broken off.

What's more, recent legislation has made the Showa system itself into the law of the land. For 1,600 years or so, Japanese Emperors customarily gave poetic names to their reigns, names by which the monarchs themselves are known after they rejoin the Sun Goddess. The present Emperor selected Showa, 'auspicious peace', as the nte of his reign (already the longest in Japanese history) and as of now Japan is officially not enjoying the rainy summer of 1979, but that of `Showa 54'. h On the defence front, a lot is happening,

Japanese standards. The Japanese

efence White Paper, just out, says that military tension in Asia is rising (really?) `,!nci for the first time points directly at the ?oviet Union as the source of the trouble. vPrevious Japanese White Papers spoke „aguelY about repelling aggressors, and Zee the aggressors have to get here by sea, the e mericans are already here, and the Chinnse have no navy to speak of, you didn't _eed a Japanese calculator to select the !avourite. This time, however, the Soviet wbu.ild-up in the Pacific is described at length, d "h such spine-chilling details as the ,,eP-i oYment of the Backfire Bomber and einre_arrival of the 44,000 ton Russian airvl I ivostok. All this, says the Japanese Vi carrier, Minsk, now home-ported in defence agency, is 'a matter of grave conCern,' This new outspokenness has led to a rare public row between the Defence Agency attd the urbane, internationally-minded Japanese Foreign Ministry. The diplomats eo mplain that all this talk about the Rus

sians are coming just plays into the hands of the Soviets, whose whole idea is to exert political pressure by intimidating people with their new weapons. In fact, Minsk is an anti-submarine ship, whose plain target is the American nuclear submarine fleet in the Pacific, while the Backfires are there to take out Chinese industrial and nuclear capability if, and when, Chinese push comes to Soviet shove. The Japanese Defence Agency is simply trying to scare an increased military budget out of the sceptical Japanese people, a ploy common enough in other countries, but not seen in Japan for more than 30 years.

Finally, the Director-General of the Defence Agency himself, Ganri Yamashita, is just back from his first week-long visit to South Korea, and long and highly publicised talks with the Korean generals. Clearly this is a toe dipped in the water, and the deepest water of all, at that — nothing less than the idea of the projection of Japanese military power outside Japan itself, something which, according to the Japanese Constitution. is never ever going to happen again. Big changes are clearly under way, and one of the earliest•is likely to be in the Constitution itself.

Interesting, but what does this all mean? The first thing we can rule out, definitively, is a real revival of Tojo-worship or any other kind of romantic Japanese nationalism among ordinary people. In fact, all the signs point the other way: the world of swords and geishas and kamikaze pilots is these days in full retreat, hotly pursued by Kentucky fried-chicken ('it's chopsticklicking good'). Macdonalds' hamburgers and the disco beat.

There are, of course, quite a number of right-wing Japanese nationalists around, probably as many as there were in the Thirties, and often the same people: you can still hear dear old Bin Akao, who was in and out of just about every pre-war assassination plot, outlining his plan for world conquest to three bored office ladies every Friday lunchtime at the Tokyo equivalent of Speakers' Corner. But the old-time rightists lack either public support, or a military arm: and the interests of young Japanese are emphatically not directed towards war, guns or uniforms. It's hard to shout a convincing `banzair with a mouth full of pizza.

True, the latest polls show That 86 per cent of Japanese now approve of the existence of the Japanese armed forces, the best popularity rating they have ever had: but most people see them as an emergency service to clean up after typhoons and earthquakes, and that 14 per cent, or nearly 20 million Japanese, still oppose Japan's having any armed forces at all. The Japanese public, with long memories of the disastrous results of Tojo's policies for them, still constitute the biggest and solidest block of convinced pacifists in the world.

But Japan is indisputably moving to the right, and the proximate cause is easy to see: the Sino-Soviet split, and the resulting wars between rival groups of Asian communists. has shattered the mainly Marxist-based Japanese opposition beyond immediate repair. The Japanese Socialist Party, pacifist, anti-American, used to take Mao's China as its guiding light: they are hopelessly disoriented by a China which advises Japan to make nuclear weapons, are split into three squabbling factions, and headed for electoral disaster in the elections the Japanese conservatives are gleefully preparing for in the coming autumn.

The Communist Party of Japan has taken the lianoi side. which has led to a mending of fences with the Russians, signalled by Moscow's withdrawing its support from the breakaway 'peace and Socialism' faction of Yoshio Shiga. The Japanese communists, by embracing the Russians, have put themselves on the wrong side of the passionate Japanese desire to get their islands back, and effectively barricaded themselves out of Japanese political life. The smaller opposition parties, the Democratic Socialists, the Clean Government Party and the New Liberal Club now have no hope whatever of a balance-of-power role, and with the fading of their prospective influence on the government their sources of funds have dried up.

So. in the strongest position they have been in for years. the Japanese Liberal Democratic Party are now in a position to repay some small political debts to faithful followers, like the Tojo-loving former Colonel Okamoto, and to activate policies which have been inoperative for years through fear of street violence or Opposition uproar. Revision of the Constitution„ for instance, has been a quiet plank in the party's platform since the Fifties.

The prosperous Japanese Conservatives are not, however, about to wage aggressive or any other kind of war. nor encourage others to do so. As long as Japan's curious bureaucratic-nationalist brand of capitalism. corrupt and scandal-ridden though it is, can deliver jobs and rising living standards, nothing very dreadful is likely to happen. When the imminent world depression hits the home island, however, we may see another story.

At first. the frugal and hard-working Japanese are likely to do deceptively well, as the markets dry up: but ifJapan's exports to Europe and the US really failed, the resulting economic earthquake would very likely sweep the whole peaceful structure away. All manner of political nasties, now semi-dormant in the woodwork, are ready to take wing. The other side of Japanese industriousness and loyalty is, alas, the ease with which the Japanese can be led, and misled.

From his new command post in heaven, General Tojo must be watching all this with growing enthusiasm. It's been a long wait, but if things keep working out, he may even be back in business.

Banzai!

Previous page

Previous page