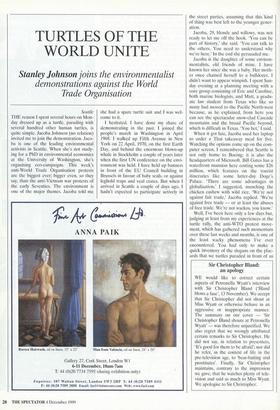

TURTLES OF THE WORLD UNITE

Stanley Johnson joins the environmentalist demonstrations against the World Trade Organisation

Seattle

THE reason I spent several hours on Mon- day dressed up as a turtle, parading with several hundred other human turtles, is quite simple. Jacoba Johnson (no relation) invited me to join the demonstration. Jaco- ha is one of the leading environmental activists in Seattle. When she's not study- ing for a PhD in environmental economics at the University of Washington, she's organising eco-campaigns. This week's anti-World Trade Organisation protests are the biggest ever; bigger even, so they say, than the anti-Vietnam war protests of the early Seventies. The environment is one of the major themes. Jacoba told me she had a spare turtle suit and I was wel- come to it.

I hesitated. I have done my share of demonstrating in the past. I joined the people's march in Washington in April 1968. I walked up Fifth Avenue in New York on 22 April, 1970, on the first Earth Day, and behind the enormous blown-up whale in Stockholm a couple of years later when the first UN conference on the envi- ronment was held. I have held up banners in front of the EU Council building in Brussels in favour of baby seals, or against leghold traps and veal crates. But when I arrived in Seattle a couple of days ago, I hadn't expected to participate actively in the street parties, assuming that this•kind of thing was best left to the younger gener- ation.

Jacoba, 29, blonde and willowy, was not ready to let me off the hook. 'You can be part of history,' she said. 'You can talk to the others. You need to understand why we're here.' In the end she persuaded me.

Jacobs is the daughter of some environ- mentalists, old friends of mine. I have known her since she was a baby. Her moth- er once chained herself to a bulldozer. I didn't want to appear wimpish. I spent Sun- day evening at a planning meeting with a core group consisting of Eric and Caroline, both marine biologists, and Matt, a gradu- ate law student from Texas who like so many had moved to the Pacific North-west because, as he explained, from here you can see the spectacular snow-clad Cascade mountains and the broad Pacific beyond, which is difficult in Texas. 'You bet,' I said.

When it got late, Jacoba used her laptop to order a Thai takeaway meal for five. Watching the options come up on the com- puter screen, I remembered that Seattle is not only home to Boeing; it is also the headquarters of Microsoft. Bill Gates has a waterfront mansion here costing some $26 million, which features on the tourist itineraries like some latter-day Doge's Palace. 'There are some advantages in globalisation,' I suggested, munching the chicken cashew with wild rice. 'We're not against fair trade,' Jacoba replied. 'We're against free trade — or at least the abuses of free trade. We're not wackos, you know.'

Well, I've been here only a few days but, judging at least from my experiences at the turtle rally, the anti-WTO protest move- ment, which has gathered such momentum over these last weeks and months, is one of the least wacky phenomena I've ever encountered. You had only to make a quick inventory of the slogans on the plac- ards that we turtles paraded in front of us as we marched the ten blocks from the United Methodist Church on Fifth Avenue to the Seattle Convention Centre. 'No Patents on Life' was one. 'No Globalisa- tion Without Representation' was another. `Up With Democracy. Down With Corpo- rate Greed. No More Naftas'. Perhaps the most telling of all the banners carried by the crowd was one which read 'WTO Fix It or Nix It'.

At least half of the participants in the march, as far as I could tell, believed that reforming the WTO was the answer, rather than closing it down. By the middle of the week the whole atmosphere sur- rounding the WTO had undergone a change, even among the official delegates, and that was before a single ministerial speech had been given.

Why are so many people so convinced that the time has come to reform the WTO? The environmentalists have cer- tainly played their part, arguing that a run of WTO decisions has threatened or diminished the right of individual coun- tries to set and maintain their own high environmental standards. Those who fol- low these matters chant their own mantras. Shrimp-turtle, tuna-dolphin, leghold traps, gasoline — all of these are cases where a WTO challenge, or the threat of a chal- lenge, is seen as leading to a dismantling of national levels of environmental protec- tion. The environmentalists even believe that WTO rules threaten existing multilat- eral agreements, such as the conventions to protect endangered species and the ozone layer, or to prevent climate change.

Lined up alongside the environmental- ists are the consumer and human-rights groups who argue that the application of world-trade rules diminishes the ability of governments to enforce, for example, high standards of health, consumer protection and labour relations. These groups, too, have their own list of case histories. There is the Guatemalan breast-milk decision where the powdered-milk companies insisted on overturning Guatemala's plans to protect nursing mothers and infants. The WTO findings against the EU ban on growth-promoting hormones in beef are another cause celebre, and one which now costs the EU some hundreds of million dollars a year in penalties. Underlying all these complaints is the subtext that, what-

ever the rights and wrongs of the case, these national (or EU) measures are in themselves an expression of 'sovereignty', and this sovereignty has been rudely violat- ed by a WTO process which is itself undemocratic and largely inscrutable. So the key issue at Seattle this week is probably not whether we have a 'new mil- lennial round' or whether we concentrate instead on the 'built-in agenda' (i.e. what was left on the table for subsequent nego- tiation at Marrakesh in 1994). The key issue is not even whether the EU agrees to further more radical negotiations on agri- culture, or how to deal with the protests of the developing countries which believe that they have not yet received the benefits they expected from trade liberalisation. The real issue at stake in Seattle is the very survival of the WTO as a credible institu- tion and its ability to regain the confidence of the public which it has so plainly lost. And this means that in addition to the spe- cific topics for negotiation — agriculture, services, investment, procurement, compe- tition, or whatever — the searchlight must be turned elsewhere, particularly on proce- dural and institutional issues.

The thousands of activists around the world (like Jacoba Johnson and her friends), who communicate by e-mail on an almost daily basis, know only too well that the real problem with WTO is a lack of transparency. They dislike many of the decisions that the WTO has taken and they would like to change the rules if they could. But far worse than this is the way the WTO takes decisions. All that could change if ministers decide to focus their attention on the procedural nitty-gritty. To be specific, the real achievement of Seattle will be if the conference agrees to re-examine the dispute-settlement mecha- nism (the distinctive feature of the WTO as compared with the old Gatt — General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade — which it replaced). Ministers could go further and instruct their negotiators to find ways of opening the dispute-settlement panels and appellate meetings to the public, and of putting the proceedings on the public record. They could also welcome 'friends of the court' submissions.

There are signs that the American dele- gation at least, led by Charlene Barshef- sky, is waking up to the realisation that it is here — on this issue of transparency and public accountability — that the real chal- lenge of Seattle lies. The EU is probably too preoccupied with its own agenda to seize the moment, but President Clinton is too canny a politician to let the opportuni- ty slip.

Stanley Johnson is an environmental con- sultant and former Conservative MEP.

Previous page

Previous page