Mediaeval Churches

WITHIN the limitations described below, the latest

• addition to the monumental Pelican History of Art is as authoritative, as widely scholarly, and as thorough as may be expected both from its author and from the series of which it forms a part. In it Professor Webb deals with British (and Irish) architecture from the seventh century to the middle of the sixteenth, when Mr. John Summer- son takes over the tale with his Architecture in Britain, 1530-1830, published three years ago, and the range of his learning is as great as anyone could wish.

But the inevitable comparison with Mr. Sum- merson's companion volume shows how far it is from what would have been possible. Professor Webb does not communicate the sense of political change, change of customs, of worship, of wealth, of ideas and ideals, in short of life as she was lived, of which architecture is the most splendid record. It is just this sense which is so abundantly present in Mr. Summerson's book. This lack is in part the natural consequence of two strangely arbitrary restrictions which Professor Webb imposes on himself. As he explains in his foreword, he denies himself the consideration of the 'social and economic forces which brought about the erec- tion of buildings of different types.' He also limits himself to those buildings whose appearance was 'dictated by non-material considerations . . . by an appeal to the imagination,' and finds that this excludes castles. (Did castles really not appeal to the imagination?) The bulk of the book thus deals with the cathedrals.

But architecture is an applied art, and buildings, however they may be treated in this book or that, are too much the product of many diverse forces to be understood apart from these forces. All the material is there, but Professor Webb, because of his deliberately shallow approach, is not really master of it. He passes from detailed description to detailed description without pausing to stand back and tell the reader what was happening in terms of those slow inner changes which alone make sense of history. There is one word which keeps recurring and which 'shows the essential aridity of the approach; the word is 'precocity.' When he comes to a new sort of building, a building which others might call original, and which raises all the crucial problems of con-

ceptual ecology—of invention versus precedent, of communication, of purpose, of historical change itself—Professor Webb calls it 'pre- cocious.' He is quite overwhelmed by the pre- cocity of Durham Cathedral, for instance, and goes so far as to call it a building which 'looks towards the future.' It is the schoolboy's 'Coming events cast their shadows before.' They don't, of course; perhaps the least interesting thing about Durham itself is that other people later built other buildings like it. What is interesting is why the builders of Durham built it unlike earlier buildings. On this and similar questions, Professor Webb falls short.

There is in fact a sort of shyness about that seizing of the manifold grains of fact and setting of them down in comprehensible handfuls of presentation and explanation which distinguishes the historian from the chronicler or the inventory clerk. I say shyness, and not inability. Every now and then a glimpse of this ordering faculty comes through, as when he gives reasons for believing that the builders of Peterborough Cathedral were familiar with the principles of harmonic propor- tion as they are expounded in Plato's Timms and in Pythagoras. But too often the dry little facts are left to speak for themselves.

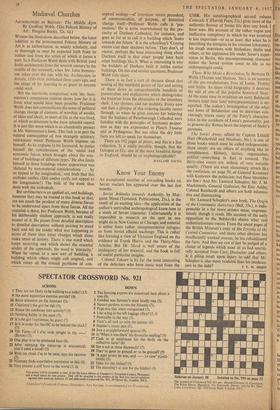

There are 192 pages of plates, and this is a fine collection. Is it really possible, though, that the Octagon at Ely, one of the most beautiful things in England, should be so unphotographable?

Previous page

Previous page