UP AMONG THE DRUG SMUGGLERS

Nicholas Shakespeare visits

a Peruvian village caught in a war over cocaine

`You should have been here 20 years ago,' is a common cry among Limenos. Darwin found them saying the same thing last century. 'Lima the horrible', as the poet Cesar Moro dubbed it, can never have been more horrible than it is today. It is not widely advertised, but more bombs go off in Lima than in any other capital except Beirut. During a single night in the Mon- terrico suburb I counted 17. (I slept through the earthquake which lasted 72 seconds and measured 5.6 on the Richter scale.) One evening the local restaurant at the bottom of my drive was sprayed with bullets and dynamited. It was full at the time.

The main source of these attacks, usually unattributed, is the terrorist organisation Sendero Luminoso, which has increasingly held the country in fee since its appearance in that year of democracy, 1980. Founded by Abimael Guzman, a leukaemic, plump- faced professor of philosophy from Ayacucho University — and author of The Kantian Theory of Space — Sendero takes its name and inspiration from a misreading of Jose Mariategui (1884-1930), a Peruvian journalist who advocated a 'shining path' which would return to the agricultural system of the Inca empire (wrongly inter- preted by Senderistas as a primitive form of communism). The first steps in return- ing the country to the Indians, who make up 49 per cent of the population, have so far resulted in the deaths of over 10,000 people. It is to be hoped that last week's spring clean of President Garcia's Cabinet — provoked by the resignation of his Prime Minister — will turn this tide.

This month the government is holding its breath in anticipation that Sendero have something particularly vengeful up their sleeve. One year ago, on 19 June 1986, after a night long mutiny, some 300 of their members and sympathisers (the figure could be more — I was quoted 900 by the editor of one weekly periodical) were massacred in the Lima prisons of Lurigan- cho, El Fronton and Santa Barbara.

The circumstances remain unclear and the perpetrators mostly unpunished, this despite President Garcia's acknowledge- ment of an 'horrendous crime that has no precedents' and his promise that 'either all the culprits go or I go'. In the past fortnight word went round that Sendero intended some form of anniversary retribu- tion. At 3pm on 19 June the minister of the interior appeared on television and alerted the nation to a wave of indiscrimin- ate attacks planned for that night. People rushed home in a panic and by late afternoon the centre of the city was dead. It was about the only night of the year when nothing happened.

To get away from the bombs, I flew east to a mission among the Indians who would, if Sendero had its way, re-inherit the power wrested from them by a pig-farmer from Estremadura four centuries ago. In fact Sendero turned out to be the least of these gentle people's problems.

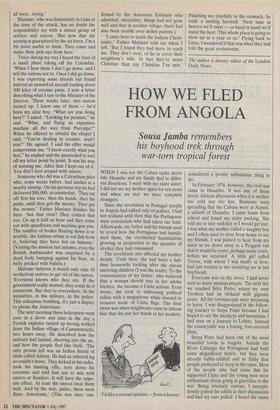

The mission of Cutivireni was founded 18 years ago by an American Franciscan called Mariano Gagnon. He hailed from Manchester, near Boston, and he had come after hearing a bishop give a talk on Peru and ask for volunteers to work among the Indians. His had been the first hand to go up.

Cutivireni is one of the most beautiful and remote places in Peru, reached by a Buffalo flight over the Andes — during which you suck oxygen from a tube — and a half-hour trip by Cessna from the jungle town of Satipo. It looks out over two rivers, a mountain range yet to be surveyed and some of the most dangerous territory in the country. For the left bank of the River Ene is the province of the drug traffickers, or narco-traficantes, polyga- mous men with nicknames like El Lobo, The Wolf.

In 1986 the export value of cocaine smuggled from Peru was $4 billion. Given two years to operate in complete freedom, the drug baron Mosca Loca promised in 1980 he could pay off Peru's entire external debt (then $9.2 billion). Today, an inability to pay off even the interest has meant Alan Garcia's government is beholden to the Americans for foreign aid. The pound of flesh demanded, in a confusion of domestic with foreign policy, is the suppression of the cocaine trade.

`You just missed the helicopters,' said Father Mariano, scratching his naked, glistening belly. He had driven to the plane in a tractor and a pair of shorts. 'They dropped eight bombs on narco airstrips over that hill. Apparently,' he added furiously, 'there were three Americans on board.'

We sat drinking beer in the mission, overlooking paradise, and Mariano talked of the 600 or so Indians whose customs and very existence he was protecting. Far from escaping the country's problems — which included its legacy of foreign interference — I had come to a place which was their microcosm. 'You have the mestizo settlers coming from the mountains, you have the military, you have Sendero and you have the narcos.'

The last two groups are useful to each other, if only to dilute the strength of the military and encourage the breakdown of order. Originally dismissed by the govern- ment as 'a tiny band of crazed narco- terrorists', Sendero gains many of its funds by exerting a toll on the drug-smugglers. What all the groups have in common is a desire for the hearts of Mariano's Indians — and failing that their land. One evening in 1984, a group of 70 men entered and burnt the mission, throwing home-made bombs at the tabernacle, razing Mariano's house and clinic and letting off machine- guns. So frightened was one boy, he scampered off leaving his glass eye to melt in the blaze.

The village remained untouched, but such is Mariano's standing with his flock that the Indians gathered for revenge. 'On Tuesday they came down from the hills, all painted black and stamping their bows on the ground. Wednesday they mixed a drink which sort of wound them up and meant they either had to kill those responsible or kill themselves. They collected in the square, so many that they spilled into my compound. Mario, their chief, turned to me and said "Do you agree, padre, we should kill them?" "Mario," I said, "remem- ber, when you asked me to baptise you, what you promised? No vengeance. You too, Francisco. Egalimente, Bonifacio," I said, one by one looking at those I had baptised. And then Mario put down his spear and burst into tears.' He takes pleasure in recalling his role as peace- maker. 'You can cut an Indian's arm off and he won't show emotion, but there they all were, crying.'

Mariano, who was fortunately in Lima at the time of the attack, has no doubt the responsibility lay with a mixed group of settlers and narcos. 'But now that my airstrip is guaranteed by the air force, I'm a bit more useful to them. They come and make their pick-ups from here.'

Twice during my stay I heard the buzz of a small plane taking off for Colombia. `When I hear them I don't go down, and I tell the natives not to. Once I did go down. I was expecting some friends but found instead an unmarked aircraft loading about 500 kilos of cocaine paste. I sent a letter describing what I saw to the Minister of the Interior. Three weeks later, two narcos turned up. I knew one of them — he'd been my altar boy. "What are you doing here?" I asked. "Looking for peanuts," he said. "What, and flying an expensive machine all the way from Puccalpa?" When he offered to rebuild the chapel I said, "You're dealing in cocaine, aren't you?" He agreed. I said his offer would compromise me. "I know exactly what you feel," he replied and the proceeded to reel off my letter point by point. It was his way of warning me. After that I kept out of it. You don't fool around with narcos.'

Someone who did was a Colombian pilot who, some weeks before, had landed at a nearby airstrip. On his previous trip he had delivered $80,000, in counterfeit. 'They cut off first his toes, then his hands, then his penis, until they got the money. They got the money.' Father Mariano finishes his beer. 'See that river? They control that too. Go up it half an hour and they come out with speedboats and machine-gun you. The number of bodies floating down is so terrible, the Indians refuse to eat fish from it, believing they have fed on humans.' (Visiting the mission last autumn, even the British Ambassador was surprised by a dead body bumping against his boat, its belly pricked with bullets.) Mariano believes it would only take 50 worked-up natives to get rid of the narcos. `Everyone knows who they are. If the government really wanted, they could do it tomorrow. But they're everywhere. In the ministries, in the military, in the police. This ridiculous bombing, it's just a display to please the Americans.'

The next morning three helicopters went over in a drove and later in the day a French explorer turned up having walked from the Indian village of Camantavachi, two hours away. He described how the military had landed, shooting into the air, and how the people fled like birds. 'The only person left was an Indian friend of mine called Adrian. He had an infected leg so couldn't move. They kicked in his radio, took his hunting rifle, tore down his coconuts and told him not to mix with narcos or Sendero. It will have the oppo- site effect. At least the narcos treat them well. And by the way, padre, there were three Americans.' (This was later con- firmed by the American Embassy who admitted, sheepishly, things had not gone well and that in another village, there had also been trouble over stolen parrots.) `I came here to teach the Indians Christ- ianity,' Father Mariano told me when I left. 'But I found they had more to teach me. They don't steal, or lie or covet their neighbour's wife. In fact they're more Christian than any Christian I've met.' Punching me playfully in the stomach, he bade a smiling farewell. 'Next time in heaven we'll meet — or hand in hand we'll stand the heat. This whole place is going to blow up in a year or so.' Flying back to Lima, I wondered if that was what they had told the great evolutionist.

The author is literary editor of the London Daily News.

Previous page

Previous page