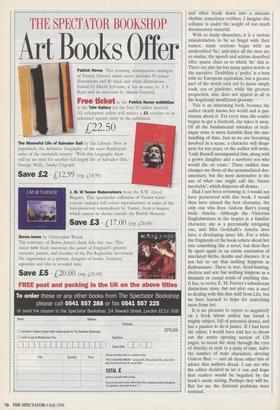

Hot spice s

but cold comfort

Sebastian Faulks

KALIMANTAAN by C. S. Godshalk Little, Brown, £14.99, pp. 472 Kalimantaan is a novel about the establishment by a young Englishman of a private raj on the north coast of Borneo in the mid-19th century. It draws on the actual experiences of the Brooke family, as recorded in various letters and diaries, but never breaks free of its documentary origins to become a proper

• novel.

C. S. Godshalk sets up her story with epic intent. Letters, noises off, drum-rolls and awed references prepare the reader for the entry of the great man, but when Gideon Barr, as he is called here, at last appears on the scene Miss Godshalk seems unsure what to do with him. He is, throughout this long book, a fugitive from his own story; the amount of space he occupies amounts to barely one page in 20. He is given to making virile, pithy pronouncements, then disappearing up country for months, or sometimes years.

In his absence a succession of empire- building men appears: Lytton, Norris, Bigelow, Dawes, Sutton, Reventlow and many more put in brief appearances, then vanish with a laconic farewell. They are all similar characters who talk in a similar way; no doubt their factual counterparts had parts to play in the Sarawak enterprise, but none of these characters pulls his weight fictionally.

The writing, meanwhile, does not seem quite right. In letters supposed to be from circa 1845 (pre-Bleak House) we find the words 'complex', 'dimensionality', `inarguable' and the phrase 'amazingly attractive'. In the narrative itself are `syn- chrony', 'synergy', 'implode', 'litany' (many times in the non-religious sense that became fashionable in the early 1980s). An author is not obliged to match her style to the period, but these terms nevertheless feel uncomfortable, as does Miss Godshalk's excessive use of the word 'roil' and its cognates.

The writing is hailed on the jacket as beautiful, but it is only the words and the things they evoke that are sometimes beautiful: parrot, opium, schooner, horn- bill, topgallant, archipelago and so on. The sentences themselves are syntactically plain and often break down into a staccato rhythm, sometimes verbless. I imagine this collapse is under the weight of too much documentary material.

With so many characters, it is a serious miscalculation to be so frugal with their names; many sections begin with an unidentified 'he', and since all the men are so similar, the speech and actions described offer sparse clues as to which 'he' this is. There are also far too many native words in the narrative. Doubtless a `prahu' is a boat with no European equivalent, but a greater part of the words turn out to mean simply cook, sea or gardener, while the greatest proportion, alas, does not appear at all in the hopelessly insufficient glossary.

This is an infuriating book, because the author clearly knows her world and is pas- sionate about it. Yet every time the reader begins to get a foothold, she takes it away. Of all the fundamental mistakes of tech- nique none is more harmful than the mis- handling of time. Just as we are becoming involved in a scene, a character will disap- pear for ten years, or the author will write, `Lady Russell accompanied him, along with a grown daughter and a newborn son who would die en route.' These sudden time changes are those of the unassimilated doc- umentary, but the most destructive is the use of what one might call the 'future inevitable', which disperses all drama.

Had I not been reviewing it, I would not have persevered with this book. I would then have missed the best character, the only one who lives: Gideon Barr's young bride Amelia. Although the Victorian Englishwoman in the tropics is a familiar character, she is a perennially intriguing one, and Miss Godshalk's Amelia does have a developing inner life. For a while the fragments of the book cohere about her into something like a novel, but then they fly apart again in an exotic succession of unrelated births, deaths and diseases. It is not fair to say that nothing happens in Kalimantaan. There is war, head-hunting, cholera and sex; but nothing happens as a thematic or causal result of anything else. It has, to revive E. M. Forster's schoolroom distinction, story, but not plot; one is used to dealing with this thin stuff from Life, but we have learned to hope for something more from Art.

It is no pleasure to report so negatively on a book whose author has found a mighty subject, full of potential drama, and has a passion to do it justice. If I had been the editor, I would have told her to throw out the entire opening section of 120 pages; to recast the story through the eyes of Amelia; to stick to a unity of time, halve the number of male characters, develop Gideon Barr — and all those other bits of advice that authors dread. I can see why the editor decided to let it run and hope that readers would be beguiled by the book's exotic setting. Perhaps they will be. But for me the fictional problems were terminal.

Previous page

Previous page