Exhibitions 1

Alberto Giacometti (Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, till 18 October)

Seeing, not believing

Roger Kimball

`Le Chien, 1951 Paul Valery once remarked that a poem is never finished, only abandoned. It would be difficult to name an idea more charac- teristic of Romanticism. With the advent of Modernism, what changed was the mood, not the situation: incompleteness more and more became the end as well as the condi- tion of artistic creativity.

The work of the Swiss-born sculptor and painter Alberto Giacometti (1901-1966) is a Case in point. In his mature years, anyway, hardly any work of art left his studio in a state he considered finished. 'That's the ter- rible thing,' he confessed late in life: 'the more one works on a picture, the more impossible it becomes to finish it.' A paint- ing or sculpture would be started, laboured over, abandoned, picked up again, given up in despair, suddenly rediscovered, just as suddenly put down. As one critic observed, `Giacometti made a whole art out of penti- inenti.' Only time and the exigencies of exhi- bition schedules called a halt to the process.

It is curious, therefore, that 'likeness' was ever the name of Giacometti's artistic desire. Again and again he insisted that all he wanted to do was to 'copy' what he saw: to give', as he told one critic, 'the nearest possible sensation to that felt at the sight of the subject'.

As this well-chosen • and sensitively installed overview of Giacometti's work at Montreal's Museum of Fine Arts shows, he Was not talking about producing snapshots. In fact, Giacometti was an accomplished natural draughtsman. Some of his early work proves that he was well able to turn out traditional, academically accomplished representations. But the effort to achieve `likeness', to capture the sensation that the visible inspires, involved something more, something different. Achieving 'likeness' was for Giacometti a struggle of Sisyphean dimensions: ineluctable and unending, a process as imperative in its demands as it was elusive in its fulfilrnents.

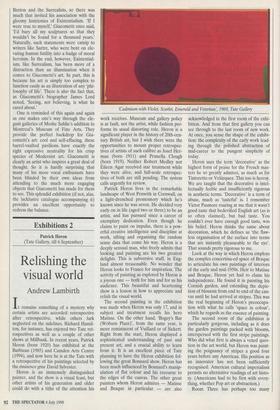

The struggle is evident throughout Gia- cometti's signature work. In sculpture, one thinks above all of the haunting elongated figures: the walking men, the women stand- ing at hieratic attention. These painstaking- ly moulded and remoulded figures — some over-life-sized, many no more than an inch tall — are bulletins from an emergency, expressive souvenirs snatched from a pool of silence, nudged into articulate presence by the sculptor's dexterity. The works not only bear the scars of their creation: they also seem to exist fully only in the evi- dences of those scars.

Something similar can be said of Gia- cometti's portraits. They are not easy works. Dark and full of occlusions, they are like stage sets upon which the sitter's humanity is patiently coaxed to reveal itself. In some ways, Giacometti's method is like that of a stone rubbing. The quick scratchings of his brush or pencil register the hard cavities and reliefs of the sitter's features — and what lies behind the fea- tures. Hence the ambivalence or ambiguity of Giacometti's portraits. The artist's mark- ings are gestures of effacement that also serve as opportunities for revelation. Gia- cometti's deftness in this regard is perhaps most clearly seen in his simplest portraits: his quick pencil portrait of Matisse (1954), for example, or his late etching of Rimbaud (1962), in which the poet's countenance suddenly crystallises from a skein-like tan- gle of lines.

The eldest son of an Impressionist painter, Giacometti was brought up in the Val Bregalia in south-eastern Switzerland `Flomme qui marche l, 1969: Fondation Marguerite et Aime Maeght, Saint-Paul near Italy. His artistic interests blossomed early and were encouraged by his family. In 1922, Giacometti went to Paris where he studied at the Grand Chaumiere with Antoine Bourdelle, a successful, somewhat pompous artist who had been Rodin's assistant. Whatever Bourdelle had to teach him, the young sculptor clearly owed much more to Brancusi, Lipchitz, and Henri Lau- rens, as well as to Cezanne and Cubism.

Like many of his contemporaries, Gia- cometti was also deeply impressed by the expressive simplicities of African and Oceanic art. The works with which he first came to notice — e.g., `Spoon Woman' (1925-1927), 'The Couple' (1926), 'Torso' (1925) — are primitivist fantasies inflected by Cubism. As with many of Giacometti's sculptures, these early pieces come with halos of allegory. They seem like displaced relics from exotic, half-remembered cere- monies: dark and often unpleasantly sexual.

It was of course this element in Gia- cometti's work — its adumbration of vio- lence and sexuality — that attracted the attention of the Surrealists. In 1930, Gia- cometti met Louis Aragon, Salvador Dali, and the Surrealists' chief minister of propa- ganda, Andre Breton. For three or four years, he was a conspicuous member of their circle, producing — if the phrase is not an oxymoron — several Surrealist clas- sics, including 'Suspended Ball' (1930), 'No More Play' (1932), 'The Palace at 4 a.m.' (1932), and 'Disagreeable Object to be Thrown Away' (1931).

Surrealist art works — when it works by conveying suggestions of significance that never quite snap into focus. Most sur- realist art depends heavily on the existence of widely shared conventions — moral and social as well as artistic conventions which it then regularly and predictably vio- lates. The expected frisson comes as much from the counter-pressure of convention as from the violation. This is one reason that most Surrealism quickly becomes boring. The works that Giacometti produced in his Surrealist phase have had such a long shelf- life precisely because their primary interest is visual, not ideological. Whatever erotic or 'transgressive' charge they may have, it is their striking formal presence — their presence as made objects — that accounts for their chief hold on our attention.

Giacometti soon parted company with the Surrealists — his return to sculpting heads from a live model was unforgivable apostasy to Breton — and later referred to his years in their camp as a 'transitional exercise' and a 'Babylonian captivity'. But his art continued to be fodder for extra- artistic ideologies. The most important of these was undoubtedly Existentialism. This association was codified as dogma — or cliché — in 1948 when Sartre wrote an essay called 'The Search for the Absolute' to accompany an exhibition of Giacometti's work in New York.

In truth, just as there was much about Giacometti that invited appropriation by Breton and the Surrealists, so there was much that invited his association with the gloomy histrionics of Existentialism. 'If I were true to myself,' Giacometti once said, `I'd bury all my sculptures so that they wouldn't be found for a thousand years.' Naturally, such statements were catnip to writers like Sartre, who were bent on ele- vating human futility into a badge of moral heroism. In the end, however, Existential- ism, like Surrealism, has been more of a distraction than an illumination when it comes to Giacometti's art. In part, this is because his art is simply too complex to function easily as an illustration of any 'phi- losophy of life'. There is also the fact that, as Giacometti's biographer James Lord noted, 'Seeing, not believing, is what he cared about.'

One is reminded of this again and again as one makes one's way through the ele- gant galleries of Moshe Safdie's addition to Montreal's Museum of Fine Arts. They provide the perfect backdrop for Gia- cometti's art: cool and self-effacing, these barrel-vaulted pavilions have exactly the right expressive neutrality for his crisp species of Modernist art. Giacometti is clearly an artist who inspires a great deal of thought. So it is hardly surprising that many of his more vocal enthusiasts have been blinded by their own ideas from attending to the much more engaging objects that Giacometti has made for them to see. This splendid exhibition (if not, alas, the lacklustre catalogue accompanying it) provides an excellent opportunity to redress the balance.

Previous page

Previous page