Notebook

For once, a story about the Poles with a happy ending. The splendid new Polish i Lb.rary has just opened in Hammersmith. 1:lus gleaming cultural centre is a far cry ,'roin the old Polish Naval Club on Chelsea rnbankment where I used to stay in the late 'fifties, a gentle, shabby place where a lady pianist played Chopin on Tuesday evenings and there was bortsch and melancholy every day. The affable Lord Donaldson's visit to the new library might lead one to think that this tdnne at least the British government had Tone Something to help the Poles. Not so. ; library was built, at a total cost of nearly th2 alillion, entirely out of funds raised by a e Polish community. In fact, it was only talt at all because in 1966 the British goyernment cut off its grant and tried to disperse the library and grab the books. NY. hen the Poles, led by the late Count 4'ailloyski, protested, the Department of i cAzIneation and Science claimed that t (12;wned most of the books because it had en subsidising the library, although in fact I7Ile bulk of the collection had been donated Ye Poles. When this grotesque line of argucot failed, the Ministry then suggested enat the books should be handed over to the tjel?tre of Russian Studies at Birmingham • niversitY — a suggestion of spectacular Insensitivity. A posse of pro-Polish peers, The by Lord St Oswald, counter-attacked. tiihe government retired in confusion, but ndoubtedly it was acting in accordance with Harold Wilson's belief that 'the Poles slionld cease to be treated as a separate entity and should be increasingly integrated Into the wider British community'. _It is still not too late to make some 4,mends for this shameful period. The DES tu?es make a small annual payment to the tilhbrarY for its services to the universities. r e grant runs out this year. It ought to be e

ncwed.

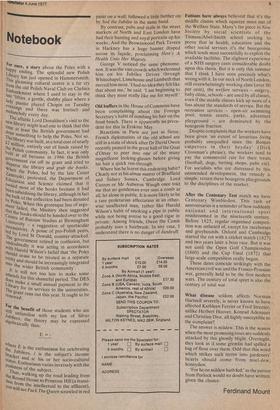

'().r the benefit of those students who are !till unfamiliar with my law of Silver Jubilees, the theory may be expressed algebraically thus: Where E is the enthusiasm for celebrating !sue Jubilees, i is the subject's income 'racket and sc his or her socio-cultural status. Enthusiasm varies inversely with the Poshness of the subject. the walking up the road leading from :le Round House to Primrose Hill (a transition from the intellectual to the affluent), You will see Fuck The Queen scrawled in red

paint on a wall, followed a little further on by Sod the Jubilee in the same hand. By contrast, pubs and stalls in the street markets of North and East London have had their bunting and royal portraits up for weeks. And the Brownswood Park Tavern in Hackney has a huge banner draped across its facade, proclaiming Here's A Health Unto Her Majesty.

George V noticed the same phenomenon. It was the vast crowds which welcomed him on his Jubilee Drives through Whitechapel, Lirnehouse and Lambeth that moved him most. 'I had no idea they felt like that about me,' he said. 'I am beginning to think they must really like me for myself.'

Old buffers in the House of Commons have been complaining about the Foreign Secretary's habit of combing his hair on the front bench. There is apparently no precedent for this in Erskine May. Reactions in Paris are just as fierce. French diplomatists of the old school are still in a state of shock after Dr David Owen recently paused in the great hall of the Quai d'Orsay to peer into one of the many magnificent looking-glasses before giving his hair a quick run-through. Where has he learnt this endearing habit? Clearly not at his almae matres of Bradfield and Sidney Sussex, Cambridge. Lord Curzon or Mr Auberon Waugh once told me that no gentleman ever uses a comb at all, let alone in public. It is more likely to be a rare proletarian affectation in an otherwise unaffected man, rather like Harold Wilson's habit of smoking a pipe in public while not being averse to a good cigar in private. Among friends, Owen the Comb probably uses a hairbrush. In any case, I understand there is no danger of dandruff. Fabians have always believed that it's the middle classes which squeeze most out of the Welfare State. Many's the piece in New Society by social scientists of the Titmuss/Abel-Smith school seeking to prove that in health, education and the other social services it's the bourgeoisie which tends most successfully to exploit the available facilities. The slightest experience of a NHS surgery casts considerable doubt upon this thesis. But it is only this summer that I think I have seen precisely what's wroniwith it. In our neck of North London, still overwhelmingly working class (over 80 per cent), the welfare services — surgery, baby clinic, schools — are used by all classes, even if the middle classes kick up more of a ' fuss about the standards of service. But the recreation services — open-air swimming pool, tennis courts, parks, adventure playground — are dominated by the bourgeois fraction.

Despite complaints that the workers have been given 'an extent of luxurious living probably unequalled since the Roman emperors in their heyday' (Dick Crossman's phrase), the workers tend to pay the commercial rate for their treats (football, dogs, betting shops, pubs etc). For socialists who are distressed by this unintended development, the remedy is simple: return these bourgeois playgrounds to the disciplines of the market.

After the Centenary Test match we have Centenary Wimbledon. This rash of anniversaries is a reminder of how suddenly national and international sport mushroomed in the nineteenth century. Before 1825, regular organised competition was unheard of, except for racehorses and greyhounds. Oxford and Cambridge started the rot with a cricket match (1827) and two years later a boat race. But it was not until the Open Golf Championship (1860) and the Cup Final (1872) that large-scale competition really began.

These dates coincide strikingly with the American civil war and the Franco-Prussian war, generally held to be the first modern wars. The century of total sport is also the century of total war.

What disease seldom affects Norman Hartnell severely, is never known to have , affected Kathleen Ferrier or Fred Streeter, unlike Herbert Hoover, Konrad Adenauer and Christian Dior, all highly susceptible to the complaint?

The answer is mildew. This is the season when the most promising roses are suddenly attacked by this ghostly blight. Overnight, they look as if some gremlin had spilled a bag of flour over them. Odd that this word which strikes such terror into gardeners' hearts should come from miel-dew, honeydew.

'For he on mildew hath fed,' as the person from Porlock would no doubt have written, given the chance.

Ferdinand Mount

Previous page

Previous page