The last Groucho Marx show

Charles Foley

Santa Monica

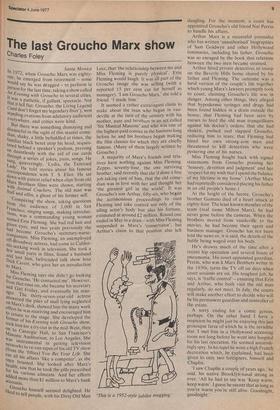

In 1972, when Groucho Marx was eightyOne, he emerged from retirement — some would say he was dragged — to perform in person for the last time, taking a show called An Evening with Groucho to several cities. It was a pathetic, if gallant, spectacle. Not that it fell flat: Groucho, the Living Legend ('and don't forget my legendary liver'), won standing ovations from adulatory audiences everywhere, and critics were kind. But there was something dismaying and distasteful in the sight of this Master comedian, shaky, a little befuddled at times, the familiar black beret atop his head, sequestered behind a speaker's podium, pressing O n dauntlessly with the aid of cue cards through ugh a series of jokes, puns, songs. He sang, Lad.quaveringly, 'Lydia, the Tattooed rw He told stories about his famous correspondence with T. S. Eliot. He sat down with patent relief when clips from old Marx Brothers films were shown, starting With Animal Crackers. The old man was `rail and elfin, a ghost of his former self. 'Compering' the show, taking questions • from the audience of 3,000 in San rrancisco, singing songs, making introductions, was a commanding young woman named Erin Fleming. She had red hair and green eyes, and two years previously she had become Groucho's secretary-nursecompanion. Miss Fleming, an unemployed off-Broadway actress, had come to Californf ia seeking work in television. She took a ew small parts in films, found a husband and lost him, befriended talk show host bick Cavett, who gave her an introduction to Marx.

Miss Fleming says she didn't go looking pr Groucho. 'He contacted me'. However, trom that time on, she became his secretary and Girl Friday, and eventually his man a ger. The thirty-seven-year-old actress answered the piles of mail lying neglected On Marx's desk, showed him the many work Offers he was receiving and encouraged him .9 return to the stage. She developed the format of his Evening with Groucho show, took him for a try-out in the mid-West, then ?n to Carnegie Hall, to San Francisco's Masonic Auditorium, to Los Angeles. She was instrumental in getting television networks to re-run tapes of his old TV show (from the 'fifties) You Bet Your Life. She ran all his affairs 'like a computer', as she °, rice boasted. She looked after Marx's nealth, saw that he took the pills prescribed for his various ailments. And her efforts added more than $1 million to Marx's bank accounts.

Groucho himself seemed delighted. He liked to tell people, with his Dirty Old Man

Leer, that 'the relationship between me and Miss Fleming is purely physical'. Erin

Fleming would laugh. It was all part of the Groucho image. she was selling (with a reported 15 per cent cut for herself as manager). 'I am Groucho Marx,' she told a friend. 'I made him.'

It seemed a rather extravagant claim to make about the man who began in vaudeville at the turn of the century with his mother, aunt and brothers in an act called 'Six Musical Mascots' and who was one of the highest-paid comics in the business long before he and his brothers began making the film classics for which they are chiefly famous. (Many of them largely written by Groucho.) A majority of Marx's friends and relatives have nothing against Miss Fleming. Zeppo, seventy-four, the one surviving brother, said recently that she'd done a fine job taking care of him, that the old comedian was in love with her and thought her 'the greatest girl in the world'. It was Groucho's son Arthur, fifty-six, who began the acrimonious proceedings to oust Fleming and take control not only of the ailing actor's body but also his fortune, estimated at around £2 million. Round one ended in May in a draw — with Miss Fleming suspended as Marx's 'conservator', but Arthur's claim to that position also left dangling. For the moment, a court has appointed Groucho's old friend Nat Perrin to handle his affairs.

Arthur Marx is a successful journalist who has written 'unauthorised' biographies of Sam Goldwyn and other Hollywood luminaries, including his father. Groucho was so enraged by the book that relations between the two men became strained.

Arthur hired private detectives to snoop on the Beverly Hills home shared by his father and Fleming. The outcome was a lurid version of the couple's life together which young Marx's lawyers promptly took to court, claiming Groucho's life was in danger. Among other things, they alleged that hypodermic syringes and drugs had been found hidden in a drain outside the house; that Fleming had been seen by nurses to feed the old man tranquillisers against his doctor's orders; that she had shaken, pushed and slapped Groucho, reducing him to tears; that Fleming had hired her own strong-arm men and threatened to kill detectives who were pestering one of his nurses.

Miss Fleming fought back with signed statements from Groucho praising her 'honesty, devotion and judgment' and her 'respect for my wish that I spend the balance of my lifetime in my home'. (Arthur Marx had reportedly considered placing his father in an old people's home.) At the height of the furore, Groucho's brother Gummo died of a heart attack at eighty-four. The least known member of the team (real name Milton Marx), he had never gone before the cameras. When the brothers moved from vaudeville to the movies, he had become their agent and business manager. Groucho has not been told the news or, it is said, the details of the battle being waged over his body.

He's drowsy much, of the time after a recent hip operation and several bouts of pneumonia. His court-appointed guardian, Perrin, who was -a Marx Brothers writer in

the 1930s, turns the TV off on days when court sessions are on. His toughest job, he says, is 'traffic control' — ensuring that Erin and Arthur, who both visit the old man regularly, do not meet. In July, the courts will make another effort to decide who will be his permanent guardian and controller of the estate.

A sorry ending for a comic genius, perhaps. On the other hand I have a suspicion he might just be enjoying this last grotesque farce of which he is the invisible star. I met him in a Hollywood screening room not long before he went into hospital for his last operation. He seemed astonishingly spry. In his lapel he wore a high French decoration which, he explained, had been given to only two foreigners, himself and Chaplin.

'I saw Chaplin a coupie of years ago,' he said, his native BrooklYn-nasal strong as

ever. 'All he had to say was 'Keep warm, keep warm'. I guess he meant that as long as you're Warm you're still alive. Goodnight, goodnight.'

Previous page

Previous page