Black and British in Brixton

Roy Kerridge

'T think Mrs Thatcher is a fine woman and 1 I'm going to vote for her,' a St Lucian housewife told her demure 14-year-old daughter. 'But I'm afraid that young peo- ple will vote Labour because they're wor- ried about unemployment.'

These spontaneous remarks, heard over a baCkyard wall, are the closest to comfort I can offer to Mrs Thatcher in her quest for the black vote. In a school playground nearby, where nearly all the children are of West Indian descent, the bullying question is 'Labour or SDP?' Conservatives never come into it.

'I hate Mrs Thatcher's guts!' a nine-year- old boy told me, but he couldn't say why.

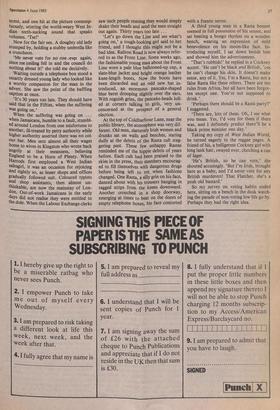

The myth that Labour is the coloured man's party seems as hard to dispel as it would be to foster another myth on behalf of the Conservatives. This, however, Saat- chi and Saatchi have tried to do, with a full- page advertisement in West Indian World showing a very black young man standing haughtily beside a caption: 'Labour says he's Black. Tories say he's British'.

Every attempt until now to better the lot of West Indians and their descendants in Britain has resulted in the setting up of mild forms of apartheid, welcomed both by the white people who want to wash their hands of the whole affair and by the glib 'profes- sional blacks' who promise to take the burden on themselves in return for grants. It would be refreshing to learn that at last the Conservatives have realised that there is no burden, and that for instance juvenile crime is not 'West Indian culture' but simp- ly juvenile crime. Under the headline 'Not Black but British', a headline that is not properly explained and seems to proclaim that black is white, there is the same old stuff about all the goodies promised specifically to black people. Much is made of the abolition of 'sus', as if coloured peo- ple are suspicious characters by birthright. Ironically, West Indians had thought of themselves as British until they arrived in England, and have only settled for the pseudo-nation of 'blackness' as a last resort. The advertisement seems to pile con- fusion upon confusion, and the promise that everything will end happily because of micro-electricity does not reassure me. In an article in the same paper, Willie Whitelaw promises millions of pounds for 'ethnic minorities' under the headline 'Tories Don't Regard Blacks as Special Case'.

Absurd as the advert is, it has given me the excuse to go to Brixton and ask other people what they thought of it. Contrary t° popular belief, Brixton is not 'another Harlem', but then I doubt if Harlem is either: at the age of 16 my sister had walked cheerfully all over Harlem on her own and travelled back to Queens by underground train at four in the morning. However, Brixton is part of Lambeth, a marginal con- stituency whose fate could be decided by the West Indian vote. Here, as elsewhere in London, resigned-looking West Indians, middle-aged and elderly, leaned side by side against metal traffic barriers at the road- side, gazing at the stream of cars going by Each seemed to be in a reverie, like a man resting on a gate in the countryside when the sun goes down. Now and again they spoke, and none seemed at all surprised when I joined in with my impertinent queries. Few said they would bother to vote, but those that would chose Labour. 'We need a change, due to the hardships of life' .. `We pray that Labour or the Alliance will win' ... 'One thing we thank God for is that when there's an election here, no one gets killed. But this country is no good. See, the sun is out, but it's cold!' Then, with some embarrassment, I pro- duced combined work of Saatchi and Saatchi. 'No need to feel embarrassed,' said the elderly man whose sparse white moustache contrasted with the dark face behind it. 'The young man in the picture is handsome of well-dressed, eclloiodruerssed, and I'm sure he's proud f his Gathering round, people tried to puzzle out what the advert meant. All were dis- appointed that the man was not standing for Parliament. None of them seemed to shuapypeohseaed , syrdcoofntthroevaedrver.t before, despite the 'We?h, o is he?' I was asked. 'Was he born her 'Is he Saatchi?' a young man asked with a straight face that defied scrutiny. When it turned out that I could answer few of these questions, the men lost in- terest, and one hit at the picture contemp- tuously, uttering the world-weary West In- dian teeth-sucking sound that speaks volumes. 'Tsel' Now for the fair sex. A doughty old lady stumped by, holding a stubby umbrella like a truncheon.

'Me never vote for no one I ever again, since me 'ceiling fell in and the council do nothing about it!' she told me decisively.

Waiting outside a telephone box stood a smartly dressed young lady who looked like a worthy companion for the man in the advert. She saw the point of the baffling caption at once.

`It's 30 years too late. They should have said that in the Fifties, when the suffering was going on.'

When the suffering was going on ... when Jamaicans, humble to a fault, stumbl- ed around London from one misfortune to another, ill-treated by petty authority while higher authority asserted there was no col- our bar. Men sent almost all their wages home to wives in Kingston who wrote back angrily at their meanness, believing England to be a Horn of Plenty. When Harrods first employed a West Indian salesgirl, it was an occasion for rejoicing and rightly so, as lesser shops and offices gradually followed suit. Coloured typists and shop assistants, then almost un- thinkable, are now the mainstay of Lon- don. Out-of-work Jamaicans in the early days did not realise they were entitled to the dole. When the Labour Exchange clerks

saw such people coming they would simply shake their heads and send the men straight out again. Thirty years too late

'Let's go down the Line and see what's going on,' a tough-looking girl said to her friend, and I thought this might not be a bad idea. Railton Road is now always refer- red to as the Front Line. Some weeks ago, the fashionable young man about the Front Line wore a pale blue ballooned-up cap, a slate-blue jacket and bright orange leather knee-length boots. Now the boots have been discarded and an odd new hat in- troduced, an enormous pancake-shaped blue beret drooping slightly over the ears. With roguish grins, the pancake-heads loll- ed at corners talking to girls, very un- concerned at the prospect of a general election.

At the top of Coldharbour Lane, near the public library, the atmosphere was very dif- ferent. Old men, slatternly Irish women and drunks sat on walls and benches, staring dully at the debris of the Rasta cult stag- gering past. These few unhappy Rastas reminded me of the hippie debris of years before. Each cult had been praised to the skies in the press, their members encourag- ed to fill themselves with dangerous drugs before being left to rot when fashions changed. One Rasta, a silly grin on his face, danced about with his trousers hanging in ragged strips from the knees downward. Another crouched in a shop doorway, emerging at times to beat on the doors of empty telephone boxes, his face contorted

with a frantic terror.

A third young man in a Rasta bonnet seemed in full possession of his senses, and sat beating a bongo rhythm on a wooden bench, wearing an expression of mild benevolence on his moon-like face. In- troducing myself, I sat down beside him and showed him the advertisement.

'That's rubbish!' he replied in a Cockney accent. 'He can't be black and British, 'cos he can't change his skin. It doesn't make sense, any of it. Yes, I'm a Rasta, but not a false Rasta like these others. There are ten rules from Africa, but all have been forgot- ten except one. You're not supposed to drink.'

'Perhaps there should be a Rasta party?' I suggested.

`There are, lots of them. Oh, I see what you mean. Yes, I'd vote for them if there was, and I definitely predict there'll be a black prime minister one day.'

Taking my copy of West Indian World, he turned eagerly to the reggae pages. A friend of his, a belligerent Cockney girl with long lank hair, swayed over, clutching a can of lager.

`He's British, so he can vote,' she shouted accusingly. 'But I'm Irish, brought here as a baby, and. I'd never vote for any British murderers! That Flatcher, she's a posh old bastard.'

So my survey on voting habits ended here, sitting on a bench in the dusk watch- ing the parade of non-voting lowlife go by. Perhaps they had the right idea.

Previous page

Previous page