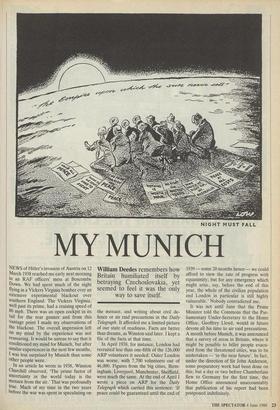

MY MUNICH

William Deedes remembers how Britain humiliated itself by betraying Czechoslovakia, yet seemed to feel it was the only

way to save itself.

NEWS of Hitler's invasion of Austria on 12 March 1938 reached me early next morning in an RAF officers' mess at Boscombe Down. We had spent much of the night flying in a Vickers Virginia bomber over an extensive experimental blackout over southern England. The Vickers Virginia, well past its prime, had a cruising speed of 80 mph. There was an open cockpit in its tail for the rear gunner and from this vantage point I made my observations of the blackout. The overall impression left on my mind by the experience was not reassuring. It would be untrue to say that it conditioned my mind for Munich, but after similar experiences in the next few months, I was less surprised by Munich than some other people were. In an article he wrote in 1938, Winston Churchill observed, 'The prime factor of uncertainty in the world today is the menace from the air.' That was profoundly true. Much of my time in the two years before the war was spent in speculating on the menace, and writing about civil de- fence or air raid precautions in the Daily Telegraph. It afforded me a limited picture of our state of readiness. Facts are better than dreams, as Winston said later. I kept a file of the facts at that time.

In April 1938, for instance, London had recruited less than one-fifth of the 126,000 ARP volunteers it needed. Outer London was worse, with 7,700 volunteers out of 46,000. Figures from the big cities, Birm- ingham, Liverpool, Manchester, Sheffield, were much the same. At the end of April I wrote a piece on ARP for the Daily Telegraph which carried this sentence: 'If peace could be guaranteed until the end of 1939 — some 20 months hence — we could afford to view the rate of progress with equanimity; but for any emergency which might arise, say, before the end of this year, the whole of the civilian population and London in particular is still highly vulnerable.' Nobody contradicted me.

It was not until June that the Prime Minister told the Commons that the Par- liamentary Under-Secretary to the Home Office, Geoffrey Lloyd, would in future devote all his time to air raid precautions. A month before Munich, it was announced that a survey of areas in Britain, where it might be possible to billet people evacu- ated from the threatened cities, was to be undertaken — 'in the near future'. In fact, under the direction of Sir John Anderson, some preparatory work had been done on this; but a day or two before Chamberlain flew to Germany for the first time, the Home Office announced unaccountably that publication of his report had been postponed indefinitely. Of course the condition of civil defence, which I could keep under observation, told us very little about the state of readiness in the three other fighting services. But it was civil defence and its deficiencies that heavi- ly influenced ministers against the risk of an early war in the air. We had been warned repeatedly that civilian populations in the cities would be in far greater danger than in the first war. We expected gas, Which never materialised. 'The bomber', Mr Baldwin had said some time earlier, will always get through.' In that at least he was proved to be right. Munich is a dangerous topic on which to make assertions. Nevertheless I assert from my corner at that time that we could not risk war in September 1938. I will call only one witness in support, Harold Nicol- son, who passionately regarded Munich as a betrayal. In March 1938 he talked to Malcolm MacDonald, then in the Cabinet as Colonial Secretary. 'Malcolm says we are really not strong enough to risk a war. It would mean the massacre of women and Children in the streets of London. No government could possibly risk war when our anti-aircraft defences are in so farcical a condition. No Cabinet, knowing as they do how pitiable our defences are, could take any risk.'

have begun this recollection of Munich half a century ago at this end, because unless our defencelessness at that time is accepted, the course of events between 15 and 30 September 1938 is baffling. If it is accepted, however, awkward questions arise. Why were our defences so unready? Enough people, including Churchill him-

self, have addressed themselves to this question during the past 40 years to make a long answer unnecessary.

I have my impressions about it, just as others of my generation will have theirs.

My earliest memories are the closing scenes of the first world war and, when the wind was right, hearing the rumble of the biggest gun barrages. It is impossible to convey to later generations how deeply that slaughter implanted in hearts and minds the resolution — 'never again'. That is to say, it implanted it in the minds of the principal victors, Britain and France.

When I began work in newspapers in 1931, that war was only 12 years behind us, roughly the same distance away as Mrs Thatcher's appointment in 1975 as Leader of the Conservative party. Families were still bleeding from the war. Sunday news- papers were still publishing inquests about battles like the Somme. My mother had spinster friends who had lost someone they loved in the war and would never marry. National leaders had lost their sons. I have a collection of Baldwin's speeches; several of them carry the echo of those melancholy lines, 'On the idle hill of summer . . .

Baldwin, of course, is supposed to be the spectre behind Munich. His were the years of the locust, or so we are led to believe.

Now what is the principal charge against him? That in the general election of 1935,

he shrank from telling the truth about our

need to rearm. Let us recall the fatal words, the speech of 'appalling frankness' in November 1936. 'Supposing I had gone to the country and said that Germany was rearming and we must rearm, does any-

body think that this pacific democracy

would have rallied to that cry at that moment? I cannot think of anything that would have made the loss of the election [1935] from my point of view more cer- tain.'

Thus Churchill's first volume on the second war, The Gathering Storm, enters

in the index: 'Baldwin: confesses putting party before country.' And everyone is content to leave it there. Well they may be, because of course Baldwin was

right. The country would have rejected a programme for rearmament in 1935. The

mood was unmistakable. Rab Butler has recorded how he was reviled in the general election campaign as a warmonger and militarist on the issue of more arms. There was reason to think that the electors could have returned a Labour government on this issue. And what then?

To paraphrase Bevan, why look in the crystal when you can read Hansard?

Labour believed in collective security (which in effect meant all the sheep gather- ing in one corner of the field to face the wolf) and the League of Nations, which America had never entered and which Japan, Germany and Italy had left. Some hope! The League was impotent. Of course Baldwin was mistaken to say as much aloud. He was not, alas, at fault in his judgment.

His successor, to whom he handed the reins while I was a lobby correspondent, was Neville Chamberlain. He had been a most prudent Chancellor of the Exchequer through the worst of the recession which followed Wall Street in 1929. The last thing he desired was huge defence estimates to wreck his careful balances. Sir John Simon, who followed him as Chancellor, 1937-40, fought the service ministers and their rearming estimates every inch of the way. He was generally successful — except against Lord Swinton, who emerges in my view untarnished from a reading of Cabinet papers of that time. Swinton got the Battle of Britain fighter planes moving. Chamberlain fired him in May 1938.

Later, Swinton wrote of his interview with the Prime Minister to Ian Colvin, a contemporary of mine on the Morning Post. Colvin's intelligence work in pre-war Berlin is acknowledged by Churchill in his war memoirs. This is what Swinton wrote to Colvin of his interview with Chamber- lain: 'He gave me no reason: but the row over air strength was going on in Parlia- ment. He wanted a quiet political life and he didn't believe war was coming. He offered me other jobs in the Cabinet. . .

At this point, 50 years later, the reason- able man may well exclaim: why all the fuss? We were not ready. We postponed a reckoning with Hitler until a year later — and then we won. The brutal answer to him is that because we were not ready in 1938, we were driven to betray a small country. To save our own bacon we sought to induce Czechoslovakia to make humiliat- ing concessions to Hitler — which ulti- mately proved wholly in vain. This proud Empire sacrificed a small power to slavery. That is what turned stomachs. There is the blot we shall never quite be able to sponge away. That is what gives the episode its bitter flavour.

To its credit, the post-war Times news- paper has never sought to conceal the part it played in this betrayal and to admit its shame. Geoffrey Dawson, editor, and Barrington-Ward, his deputy, who thought too much alike for safety, determined that Britain should not go to war on behalf of Czechoslovakia. Their policy culminated in an editorial on 7 September 1938. It suggested that Czechoslovakia might be- come a homogeneous state by 'the seces- sion of that fringe of alien population who are contiguous to the nation with which they are united by race'.

The Foreign Office at once issued a statement disassociating the Government from the idea. Rab Butler, then Under- Secretary at the Foreign Office, was con- vinced, however, that his Foreign Secretary, Lord Halifax, had had a hand in it. `. . . The two Yorkshiremen were very close and I saw Dawson leaving the office on the 6th after a long interview with the Foreign Secretary.' It was no end of a lesson for editors to keep a hygienic distance between rulers and themselves.

My closest friend on the Times then was Anthony Winn. After Eton and Christ Church, Oxford, he joined the Times and in 1938 was their lobby correspondent. He wrote a note on Duff Cooper's resignation on 3 October 1938 which Dawson held out and replaced with one of his own more critical of Duff Cooper. Winn resigned. 'My distaste for what I frankly regard as a silly and dangerous policy has been hardening for weeks,' he wrote to Dawson. I rejoiced when he then joined us on the Daily Telegraph, but not for long. He was killed in action in Egypt in November 1942.

When I think back to Munich, I think of friends like Tony Winn and Ronnie Cart- land, then MP for the King's Norton division of Birmingham, who hated appeasement far more than I can claim to have done and who went on to die in action. That is one reason why Munich is such an emotional subject, and it is hard to explain now. It tore friends apart. Sir Colin Coote, later my editor on the Daily Tele- graph, was a Times leader-writer at the time of Munich. He wanted to resign, but was persuaded not to do so. One of his closest friends was Walter Elliot, Minister of Health in Chamberlain's Cabinet. After Munich, things were never quite the same between them.

It was not in the nature of Neville Chamberlain to nurse emotions of this kind. I watched him with a clear eye and firm step get into his little plane at Heston for his second visit to Hitler at 8.30 a.m. on Tuesday, 22 September. 'Unknown to Mr Chamberlain,' I wrote, 'almost the entire Cabinet arranged, late on Monday even- ing, to be present at Heston to wish him Godspeed on his fateful journey.' At one time my mother possessed a photograph of the Heston send-off in which I featured; but she never wholly approved of my hat, which in those years I dented like a pork pie, and the picture has disappeared.

Mr Chamberlain, I reported, walked through the lane of cheering friends and colleagues. 'Then he stepped to the mic- rophones and, with a smile, said: "When I was a little boy, I used to repeat, if at first you don't succeed, try, try, try again." When I get back, I hope I may be able to say as Hotspur in Henry IV, "Out of this nettle, danger, we pluck this flower, safe- ty." 'Alas, when he got to Gotesburg, Mr Chamberlain found that the bed of nettles had grown thicker. At this distance, people have probably forgotten that Chamberlain made three separate journeys to Germany in the last fortnight of September 1938.

His first, on 15 September, was to Berchtesgaden, from which I reported his return on the evening of 16 September. 'I had a long talk with Herr Hitler,' he said, `. . and I feel satisfied, now, that each of us fully understands what is in the mind of the other.' He was handed a three-page hand-written letter from the King and from the roof of the airport, I reported, 'came a woman's single cry, "Well done, Chamber- lain!" He looked pleased and raised his hat.'

On Saturday, 17 September, he gave his Cabinet a full account of his experiences, describing Hitler as 'the commonest little dog you ever saw'. The Cabinet minutes record more discreetly: 'On a first view, Hitler was unimpressive.' The Cabinet spent all Saturday on it and on Sunday ministers met the French to cobble together a plan for Czechoslovakia. The gist was that in her own interests and that of European peace Czechoslovakia would do well to transfer the Sudeten German areas to the Reich.

Armed with this, Chamberlain made his second journey, this time to Bad Godes- burg. Hitler's reception of the Anglo- French concoction was unhelpful. 'I am The British do it by declaring a Bank Holiday.' sorry, but all that is no use any more.' He added the claims of the Poles, the Hunga- rians and the Slovaks, claims that would have effectively disembowelled Czechoslo- vakia. Chamberlain, unsmilingly, took leave of Hitler. He returned to a less pliable Cabinet. The mood had altered: no more concessions to Hitler. Thus the stage was set for the final Act.

Chamberlain had almost concluded his melancholy account of events to the House of Commons on 28 September, when a note was hurriedly passed to him. Harold Nicolson has described the scene:

He adjusted his pince-nez and read the document that had been handed to him. His whole face, his whole body seemed to change. He raised his face so that the light from the ceiling fell full upon it. All the lines of anxiety and weariness seemed suddenly to have been smoothed out: he appeared ten years younger and triumphant. 'Herr Hitler', he said, 'has just agreed to postpone his mobilisation for 24 hours and to meet me in conference with Signor Mussolini and M. Daladier at Munich.'

Immediately after delivering the fateful words, . . peace with honour. I believe it is peace in our time,' Chamberlain regret- ted it. Lord Home, who had been with him in Munich, has observed that the mistake haunted him for the rest of his life. On my return to Fleet Street that night our night editor, Bob Skelton, met me in a corridor, clenched his fist, aimed an air blow at my midriff and said, 'You young fellows are for it.' He was not a man I had much time for, but he was right. In truth, after Austria had gone, Czechoslovakia with its 2,500 miles of frontier was indefensible. Our measurements were wrong. Chamberlain thought he had brought back peace. In reality he had at high cost bought a year's respite. Duff Cooper res- igned. The rest stayed. Along with the majority I hoped for the best. Not until March 1939 did I feel impelled to join the newly doubled Territorial Army. While we drilled at Wellington Barracks, ministers looked up at the darkening sky and fum- bled with incredible dilatoriness for an Anglo-Soviet pact. In the light of what happened, it was probably never within our reach.

The main failure of ministers, in my eyes, was their inability correctly to read the character and intentions of Hitler. It was not, however, nearly as easy then as it appears now. Who is prepared to de- clare, for example, they fully compre- hend the character and intentions of Gor- bachev? The failure among the rest of us lay in the incurable desire of modern democracies to beg to be excused training in their own defence. Are vve confident that Europe's wistful desire to read all the Gorbachev signs favourably does not reflect something of that kind? Churchill said that Munich was a national humiliation. We have striven for half a century to conceal that from ourselves.

Previous page

Previous page