ARTS

Exhibitions

Mission of Mersey. . .

Giles Auty

The Tate Gallery, Liverpool

Following the frenzy of media euphoria in general and of the Observer's specially produced and somewhat embarrassing panegyric in particular, what, if anything, remains to be said about the opening of the new Tate Gallery at Liverpool? Observer journalists have exhausted several years' supply of superlatives so one feels that any further reference to the new gallery direc- tor's 'silkily macho' appearance or 'bright blue eyes that can snap and crackle' - and even pop, presumably - might be viewed as excessive, not least by the good Mr Richard Francis himself. I can almost hear him looking at me.

Being privileged to be one of the enor- mous throng present on the gallery's inau- gural evening, to rub smoothly padded shoulders with major gallery owners, more celebrated critics, patrons of new art and other assorted glitterati, I would like to add my own, polite congratulations to all concerned. Nobody wishes to be a spectre at so agreeable a feast but, for some odd reason, a plaintive line from a Sixties song kept returning to me: 'But will you still love me tomorrow?' The new gallery has started off with a bang, certainly, but the greater test will come in maintaining future levels of affec- tionate interest. A disillusioned marketing executive admitted to me once: 'Most market research proves what an intelligent person has guessed already.' I recalled this on an earlier visit to the new Tate when building work was still in progress. On that occasion a spokesman assured me a marketing survey had shown that the new Liverpool Tate would be as magnetic to visitors from Leicester - or other places equidistant from Liverpool and London, one supposes - as the original Tate Gallery. On instinct, rather than evidence, I doubted this and wondered whether other marketing projections may not have been a touch optimistic also.

The Albert Dock site is uniquely im- pressive and loses nothing from the propin- quity of other grand mercantile and civic buildings. The Tate's consultant architect, James Stirling, has put a rein on his eclectic playfulness, for once, and made just about the best of his raw material. This was an old warehouse of classic proportions. In- deed, its external and internal symmetry probably made the architects' tasks much harder, through uniformity of ceiling heights, spacing of windows and so forth.

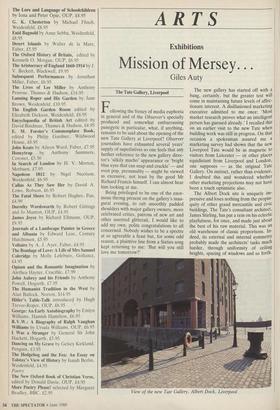

View of the new Tate Gallery, Albert Dock, Liverpool The existing ceilings are inconveniently low for a modern art gallery, not least because avant-garde artists have become accustomed by now to inflating the scale — if not the content — of their work to match the mammoth internal spaces of modern purpose-built galleries.

Because works of art are more fragile than the original merchandise — such as cotton and tobacco — stored in the 12,000 square metres of Jesse Hartley's 132-year- old warehouse, a number of additional services have had to be brought in, notably air conditioning. This runs, together with lighting, in bulky overhead ducts which sadly compromiise the integrity and shal- low curve of the old brick ceilings. One hopes that no more sympathetic solution was feasible. At the time of Lucian Freud's exhibition last December in the downstairs area of the Museum of Modern Art in Paris one was aware of a conflict not just of scale but of ethos between the compact, tradi- tionally conceived works and their over- whelming, modernistic surroundings. At the Tate, Liverpool, the exact reverse happens, where the huge, totemic paint- ings produced by Rothko — if later with- drawn — for Mies van der Rohe's Seagram Building not only dwarf the internal Spaces, in some instances through being hung too high, but are fundamentally at variance with the entire rationale of the building. One does not have to be hypersensitive to be aware of this.

On the ground floor, the second long- term exhibition of works drawn from the Tate's overall collection introduces major surrealist paintings and sculpture by such well-known figures as Chirico, Dali, Mag- ntte and Ernst. 'Scylla' by Ithell Colqu- houn stands up well in this company. The artist died recently and would have been gratified by the company she is keeping. The scale of the surrealist paintings is more suitable to the building than are the Roth- kos, yet here the stalwart, mercantile respectability of the warehouse limits not SO much the dimensions of the works as their spirit of would-be anarchy. The space has a taming and civilising effect. The third of the inaugural exhibitions, Starlit Waters: British Sculpture and Inter- national Art 1968-1988, works better than the other two in terms of proportions, but as far as content goes, I am not so sure. It is the content of the new gallery's exhibi- tions, of course, even more than the Magnificence of the premises, their conver- sion, or the surrounding landscape that will determine the long-term worth and viabil- ity of the gallery. In his inaugural address, the Arts Minister Richard Luce spoke of the need for public art galleries to listen attentively to their users. Such sentiments Will sound like heresy to those many in the modern museum hierarchy who see their roles as primarily didactic. In general, their concept of dialogue is a one-way process. I saw many of the exhibits in this particular show when they were first ac- quired by the Tate and was as irritated by them then as I am now. For example, I feel Michael Craig-Martin's glass of water enti- tled 'Oak Tree', complete with the pseudo- philosophy of its accompanying text, may have a deleterious effect on the already fuddled or dispirited. One imagines the raw vigour of recent Scottish painting might be more in sympathy with the basic Liverpudlian spirit. Only the idle have time for solipsist crises of identity and one hopes Liverpool will have far fewer idle hands in the immediate future.

On the opening evening, the gallery's initial rites were concluded by an apocalyp- tic, multi-disciplinary 'performance', com- plete with doom-laden music, spraying hosepipes and prancing figures. Handel would have provided something a touch happier, one supposes, but naturally we were not allowed to forget for a moment we were attending a relentlessly 'modern' occasion. Gusts of unseasonal rain swept the onlookers, while over the sea a pale green sunset struck an ominous note.

I hope the new Tate of the North will play a significant part in the renascence of a fine old city. But the gallery's young skipper — he of eyes like breakfast cereal — will need all his keenness of vision to steer an intelligent path.

Previous page

Previous page