Bank Shares as an Investment

ANYONE who has read Mr. J. M. Keynes' annual Address to the Members of the National Mutual Life Assurance Society and the articles and comments to which it gave rise has prob- ably gathered that, as usual, the experts hold very emphatic but quite divergent views, and that no one really knows whether Gilt-Edged stocks will rise or fall during the next twelve months, or whether now is the time to buy, or sell, Ordinary shares. If he compares Gilt-Edged prices today with those of three years ago, he will find that in spite of ruling cheap money rates War Loan has fallen by over 3 per cent. and 2i pzr cent. Consols by over 12 per cent. The difference between the two falls is remarkable, especially when it is remembered that War Loan, which has behaved relatively well on this occasion, only six years ago gave its unsuspecting holders an unpleasant shock by cutting its interest rate from 5 per cent. to 3.1 per cent. What is a per- plexed investor to put his savings into ? Part at any rate should go into the ordinary shares of British Banks, as they are the safest form of equity investment and as such are a hedge against further depreciation of the £, which is predicted in some responsible quarters.

The dividend record of the leading Home Banks for the past few years is superior to the yield on War Loan or on any other fixed-interest security which has taken advantage of cheap money to convert its rate of interest to a lower level, and the capital value has in most cases fluctuated less than that of Government Stocks. A holder of a selection of Bank Shares can also reckon on receiving an occasional bonus, and is not likely to complain if as happened recently, it is a " centenary " bonus slightly out of season.

The British Banking system is built on foundations so solid that it remained unshaken throughout the World War and the Economic Crises of recent years. British Banks are con- stantly building up reserves, disclosed and hidden, and are thus able to offer their depositors unquestioned security both in good times and in bad. This practice is equally beneficial to the shareholders.

For investment purposes British Banks may be divided into the following groups : HOME BANKS : Scottish, English and Irish.

DOMINION AND COLONIAL : African, Australian, Canadian, Indian and Far Eastern and New Zealand.

MISCELLANEOUS : South American (Bank of London and South America), and European (Hambros, British Over- seas, Imperial of Iran, National of Egypt).

HOME BANKS.—The record of the Scottish Banks is unique. None of the four independent Scottish Banks reduced their dividends during the 1931 depression, neither did Barclays, nor, of course, the Bank of England ; the latter's dividend record and that of the Bank of Scotland are very similar the Bank of England paid to per cent. from 1916 to 1921, inclu- sive, III per cent. in 1922 and 12 per cent. ever since ; the Bank of Scotland paid 16 per cent. from 1916 to 1927, inclu- sive, and has paid 18 per cent. since then. The Big Five English Banks show an impressive record of practically unvarying dividends, except for a slight reduction following the 1931 depres.;ion, and a distinct tendency at the present time to restore dividends cautiously and by degrees to the level of the pre-slump period. When comparing Bank Shares with War Loan and other Government Stocks it is well to remember that whereas any reductions in Bank divi- dends were very small, the reduction in War Loan interest was equivalent to more than 25 per cent. of the previous rate. The capital value of Bank Shares has varied relatively little, there being a definite upward long-term trend.

The year 1937 was the best year for the Home Banks since the depression. Continued cheap money has greatly enhanced the value of the Banks' assets ; revival of the " heavy " indus- tries and shipping has enabled debts, long since written off as " bad," to be repaid in full, even with arrears of interest. Bank Advances again increased and since the beginning of 1934 have grown by the substantial figure of £251 millions. or 34.1 per cent. ; it is chiefly due to this improvement in the most remunerative branch of banking that four of the seven English Banks either paid increased dividends for 1937 or declared bonuses. The current average yield on the Scottish Banks is just ander £3 15s. •per cent., on eight leading English Banks £3 16s. 3d. per cent., and the Irish Banks £4 12s. id. per cent. ; the difference illustrates very fairly the investment status of each of the three groups. The average flat yield on medium-dated Government Stocks is approximately £3 5s. fod. per cent., and the redemption yield £2 as. 6d. per cent. ; the Scottish and English Banks look' attractive by comparison.

Irish Bank Shares are not often dealt in on the London Stock Exchange. Their dividend record is not so good as that of the Scottish and English Banks and at the present time they are carrying on under difficult conditions. As long as a Tariff War and other political obstacles exist between England and Ireland, Irish Bank Shares will remain out of favour with the investor.

DOMINION, COLONIAL AND MISCELLANEOUS BANKS.—British

Banks operating through their Branches in all parts of the world are less stable than the Home Banks. For the most part they are working in countries where prosperity is linked up and tends to,fluctuate with the prices of primary products. Banks, such as the Bank of London and South America, operat- ing in foreign countries, are not likely to be greatly affected by the contemplated ban on foreign banking in Brazil. In the past there have been similar bans but the difficulties have been overcome. If necessary, use could be made of the facilities provided by holding-company finance.

There have actually been periods when the shares of the Dominion and Colonial Banks have risen whilst Home Banks have fallen. No one would be bold enough to prophesy that such a period will not recur in the future. During the five years 1916-192o, whilst Consols fell from 59 to 48, Bank of England from 212 to 179 and other Home Banks in proportion, the Dominion and Colonial Banks rose—Standard Bank of South Africa from 10 to 121, Canadian Bank of Commerce from 401 to 421, Bank of South Wales from 364 to 444, and National Bank of India from 381 to 49. The Imperial Bank of Iran has quite a remarkable record ; its dividends have steadily increased from 7s. Tax Free in 1916 to Bs. Tax Free in 1936, and the price of the shares has nearly trebled in value. Last year these Banks reflected the recovery in world trade and raw material prices ; there were nine increases in dividend in the Dominion, Colonial and Miscellaneous group. The present approximate average gross yields are : Canadian £4 15s. 6d. per cc n':., Australian £4 14s. 4d. per cent, African £4 3s. od. per cent., New Zealand (reflecting the unsettled political situation and the repeated dividend reductions of the National Bank of New Zealand from 14 per cent. in 1929 to 4 per cent. in 1936) Ls Ifs. iod. per cent.

Although in a lower investment category than the Home Banks, these Banks cater for countries which for the most part have a great development before them. They are patterned very largely on the Home Banks and each successive slump and recovery contributes something to a more solid foundation. Recovery from the 1931 depression has been slow but none the less sure. The low commodity prices then touched are unlikely to be repeated in the near future. An investment wisely spread over the best shares will give a very attractive yield, and taking the medium long view, should appreciate in value.

As will have been seen it is not difficult to make out a strong case for Bank Shares. And yet they are not, with few excep- tions, popular with small investors. Whereas the average individual investment in the ordinary shares of large industrial companies and in the certificates issued by Unit Trusts is between kip to £200, in the case of the seven leading English Banks it is probably between L40o and k500, and in one or two of the Banks even higher. The reasons are obvious : (i) " Heavy " price, (ii) Liability in respect of uncalled capital, and (iii) A not very free market on the Stock Exchange. (i) " Heavy " price. Shares selling at £30 to L40 each are unlikely to appeal to the investor accustomed to buy in lots of is() ; several of the Banks have made attempts to overcome this difficulty by subdividing their shares (usually one into five or ten shares), e.g., the National Provincial in 1938, the Provincial Bank of Ireland in 1936, Westminster Bank and the National Bank in 1929, Union Bank of Scotland in 1924, Lloyds in 1920, Union Bank of Australia in 1919, Commercial Bank of Scotland in 1919 and again in 1929, &c., but the process is slow and fortunately for the shareholders the subdivided shares seem to swell again. (ii) Liability. The majority of Bank shares quoted on the London Stock Exchange are partly- paid, e.g., there is a liability on the shareholder to pay up, if required, the amount of the uncalled capital. There is another form of liability called " reserve " liability by which the shareholder is only liable in the event of the Bank going into liquidation. The idea of one of the " Big Five " going into liquidation is so unpractical that no one today looks upon " reserve " liability as a risk that needs seriously be considered. But Trustees may not, without special arrangements, hold partly-paid shares and Banks generally refuse to register them in their name. There is a tendency for the liability on partly-paid shares to disappear and Banks from time to time to capitalise reserves and apply them in paying up part of the uncalled liability on their shares. Uncalled liability is a relic from the early days when it was thought to be a safeguard to the depositors to be able to call upon the unpaid capital in case of emergency. Today the published reserves of the Big Five are nearly as large as the amount of the paid-up capital and both together are small compared with the Deposits with which the Banks work. In 1937 the Capital and Reserve of the London Clearing Banks alone were £138,603,707 and the Deposits £2,344,182,812. (iii) Re- stricted Market. With the exception of the shares of the " Big Five " Banks, none of the Bank Shares can be said to enjoy as free a market on the Stock Exchange as shareholders would desire.

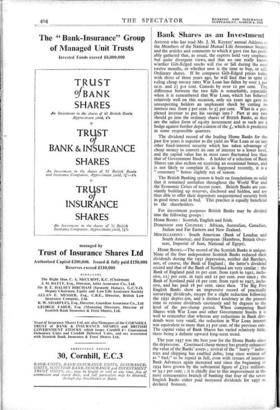

These obstacles can now be overcome by the purchase of Bank-Units of the Trust of Bank Shares, which was formed in December, 1935. Bank-Units can be bought in small quantities (from 20 Units at 18s. 6d. each), they free the holder from personal liability, are freely marketable, and by their " spread ' ensure that the Unit holder participates in any bonuses that may be forthcoming. Bank-Units also even out such moderate fluctuations as may occur in the capital value and dividends of individual banks. G. FABER.

Previous page

Previous page