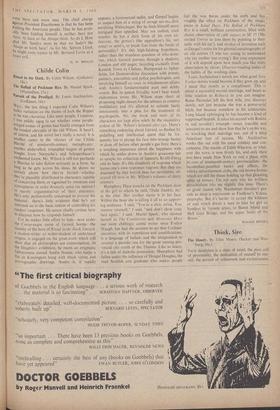

Childe Colin

The Ballad of Peckham Rye. By Muriel Spark. (Macmillan, 15s.) ursuit of the Prodigal. By Louis Auchincloss. (Gollancz, 16s.)

WELL, the last thing I expected Colin Wilson's bulky variation on the theme of Jack the Ripper to be was charming. Like most people, I suppose. I was mildly agog to see whether some purple- winged avatar of genius had finally emerged from the tousled chrysalis of the old Wilson. It hasn't, of course, and his novel isn't really a novel. It is another canto in the odyssey of our Childe Harold of nineteenth-century metaphysics : another dishevelled, triumphal wagon of golden boughs from Nietzsche'S and Schopenhauer's enchanted forest. Mr, Wilson is still too puritanic a Shavian to take fiction seriously as a form. So long as he gets across his ideas, he shows no anxiety about how _ they're ferried—whether they're plausibly distributed to characters capable of conceiving them, or sustained by emotions and atmospheres to make dramatic sense (as opposed to merely argumentative) of their utterance. He's only perfunctorily concerned to present his material: there's little evidence that he's yet cottoned on to the basic notion of controlling his readers' responses. He seems chiefly curious here to discover how he responds himself. For he makes little effort to hide--save under the Corvo-esque name of Gerard Some-- -the Identity of the hero of Ritual in the Dark. Gerard, a student-writer or writer-student of undeclared origins, is engaged on the great work which will show that all philosophies are existentialism. At the Diaghilev exhibition, he meets an enigmatic balletomane named Austin Nunne. who keeps a flat in Kensington hung with black velvet and Pornographic drawings. Austin is. it rapidly appears, a homosexual sadist, and Gerard begins to suspect him of a string of savage sex-Mi..■ ders terrifying Whitechapel. But he finds himself more intrigued than appalled. May not sadism. even murder, be but a dark form of his own en- deavour, the genius's (the apposition's his, not mine) or saint's, to break free from the limits of personality? It's this high-faluting hypothesis, rather than the mundane question of who-done- 'em, which Gerard pursues through a shadowy London and 400 pages; bicycling excitedly from Kentish Town to Chelsea, Hampstead to Spital- fields, for Dostoievskian discussion with priests, painters, journalists and police psychologists, and involving himself en route in simultaneous affairs with Austin's fundamentalist aunt and debby cousin. But its patent frivolity won't bear much elaboration (even Mr. Wilson stops short of proposing night-classes for the admass in creative mutilation) and it's allowed to subside fairly innocuously into a plea for the treatment of psychopaths. No, the book and most of its characters are kept alive solely by the inquisitive ardour of Mr. Wilson's fictional alter ego. There's something endearing about Gerard, so flushed by pedalling and intellectual quest that he fre- quently has to plunge his face into strange basins or doze off before other people's gas fires; there's a touching innocence about the happiness with which he settles down in Austin's gruesome lair to sample his collection of liqueurs. Krafft-Ebing and de Sade. It's this simplicity of response which leaves one's own responses vagrant: But they are disarmed by that boyish heat for certainties, ob- scured till now in Mr. Wilson's volumes ()I' dusty answers.

Humphrey Place knocks on the Peckham door of the girl to whom he said, 'Quite frankly, no.' at the altar. Her mother slams it in his face.

Within the hour she is telling it all to an approv- ing audience. 'I said, "You're a dirty swine. You

remove yourself," I said. "and don't show your

face again," I said.' Muriel Spark, who showed herself in The Comforters and Memento Mori

our most chillingly comic writer since Evelyn Waugh, has had the acumen to see that Cockney narrative, with its repetitions and amplifications, is a language of ballad; and the imagination to concoct a parodic one for the great unsung pro- vincial city south of the Thames. Like so many.

it's a tale of diabolic possession : Humphrey had fallen under the influence of Dougal Douglas, the mad Scottish arts graduate who makes people

feel the wee horns under his curls and has roughly the effect on Peckham of the magic piano in Salad Days. The Ballad of Peckham Rye is a small, brilliant construction, filled with choice observation of café mews in SE 15 ('He invited Trevor to join them by pointing to their table with his ear'), and strokes of invention such as Dougal's notes for his ghosted autobiography of an old actress ('1 was too young to understand why my mother was crying'). But your enjoyment of it will depend upon how much you like witty observation by clever, Observer-reading ladies of the habits of the working class.

Louis Auchincloss's novels are what good New Yorker stories would become if they grew up, and I mean that mostly as a compliment. This is about a successful second marriage, and bears as little relation to Rebecca as you can imagine. Reese Parmelee left his first wife, you discover slowly, not just becauSe she was a power-avid bitch, but because somehow in his aristocratic Long Island upbringing he has become a kind of suppressed beatnik. It takes his second wife Rosina (a real novelist's triumph--sweet, irascible and insecure) to see and show him that he's on his way to wrecking their marriage too, out of a deep American fear of success. Mr. Auchincloss works this out with his usual subtlety and con- creteness. The mantle of Edith Wharton, or what- ever she wore, is now firmly his, and only these two have made New York so real a place, with • its core of nineteenth-century provincialism—the Jacohethan-panelled banks and offices, the whisky-advertisement clubs, the old brown houses which are still the tissue holding up that gleaming spine of towers. I'm not sure why his brilliant parochialism irks me slightly this time. There's no .good reason why Manhattan 'shouldn't pro- vide as deep a microcosm as Faulkner's Yokna- patawpha. But it's harder to accept the-wildness of soul which drives a man to take his girl on Sundays to 'remote areas, to Staten Island and Hell Gate Bridge, and the upper limits of the Bronx.'

RONALD ()RYDEN

Previous page

Previous page