ARTS

Exhibitions

116th Exhibition of Watercolours and Drawings (Thos. Agnew & Sons, till 17 March) Francis Danby Jacques-Laurent Agasse (Tate Gallery, till 9 and 2 April respectively)

The tell-tale touch of red

Giles Auty

reviewing a selection of the watercol- ours assembled for Agnew's 116th Exhibi- tion of Watercolours and Drawings three weeks ago, I remarked on what a relief it was to see so many excellent works which were not ruined by picturesque touches. For me, a major disappointment of so many 19th-century watercolours is that the artist could not leave an entirely plausible river, mountain or rural scene alone but felt obliged to add a brace of reclining shepherdesses, yokels or fisherfolk. Invari- ably one or more of these wears a red shawl or bonnet. If you do not believe me, re-examine the pair of Welsh landscapes which have been in your family for genera- tions or the unattributed 'Beach Scene (Deal?)' which you bought as a snip at a Country auction. The person wearing the red article will probably be slightly to the right of centre. Why do roseate garments act as such a rag to the bull in me? Generally because the human figures, un- like the torrent, glacier or grotto, are invented rather than observed. Do you imagine the artist paid a couple of conve- niently passing shepherdesses to loll in the tussocks while he drew them? Demand for Willing shepherdesses has always exceeded supply except, perhaps, in Montmartre. The addition of figures was, of course, a Convention of its period, yet one which the very best artists managed usually to avoid.

After 116 years of presenting an annual watercolour exhibition, Messrs Agnew & Sons (43 Old Bond Street, W1) are clearly not short of practice. Their first catalogue is still in existence and one would like to think it included mention of works of the quality of the de Wints, Boningtons, Cot- mans, Constables, Turners and Gains- boroughs which spearhead the present

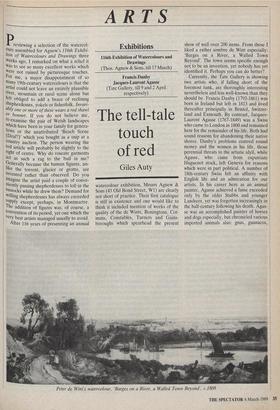

show of well over 200 items. From these I liked a rather sombre de Wint especially: `Barges on a River, a Walled Town Beyond'. The town seems specific enough not to be an invention, yet nobody has yet identified it. Perhaps you can do better?

Currently, the Tate Gallery is showing two artists who, if falling short of the foremost rank, are thoroughly interesting nevertheless and less well-known than they should be. Francis Danby (1793-1861) was born in Ireland but left in 1813 and lived thereafter principally in Bristol, Switzer- land and Exmouth. By contrast, Jacques- Laurent Agasse (1767-1849) was a Swiss who came to London in 1800 and remained here for the remainder of his life. Both had sound reasons for abandoning their native shores. Danby's problems centred round money and the women in his life, those perennial threats to the artistic idyll, while Agasse, who came from expatriate Huguenot stock, left Geneva for reasons which were in part political. A number of 18th-century Swiss felt an affinity with English life and an admiration for our artists. In his career here as an animal painter, Agasse achieved a fame exceeded only by the older Stubbs and younger Landseer, yet was forgotten increasingly in the half-century following his death. Agas- se was an accomplished painter of horses and dogs especially, but chronicled various imported animals also: gnus, guanacoS, Peter de Wint's watercolour, 'Barges on a River, a Walled Town Beyond', c.1808 quaggas and other unusual beasts beloved of compilers of crosswords. At the outset of his career, Agasse's background land- scapes were brushed in for him by others but he grew steadily in thiS and other areas of accomplishment. His portraitS remained a touch stiff nonetheless and this general characteristic, rather than lack of good draughtsmanship, held Agasse back from higher levels of achievement. His essays into imagination, such as 'The Fountain Personified'„ make one glad he did not let his own hair down more often. He was suited much better to objective drawing as in 'Fox Lying Seen Head On'. One is conscious of Agasse's perennial anxiety to please and impress his patrons. Indeed, whether the latter are the hOrsy aristocrats of his time or the tyre magnates and advertising tycoons of this century, such an attitude is always better for the pocket than the painting. Although their art has few obvious similarities, Agasse and Danby strike me as comparable cases of artists desperately conscious that a, living must be earned. Danby fell too often into the traps of the picturesque yet was keenly jealous of his status among his contemporaries. John Constable defeated him by one vote in elections to full membership of the Royal Academy in 1829, a reverse Danby attri- buted solely to money and influence. Dan- by also accused 'Mad' John Martin of plagiarism in his choice of apocalyptic subject matter, though Danby's was prob- ably the more awful, if not in the sense that he desired. Danby was twice the painter when sticking to the topographical and everyday. For instance, 'Boat-building near Dinan', c.1838, is as lovely as a contemporary Corot. Wherever his stylistic versatility allows direct comparison, it is clear why Datiby was a lesser artist than his seniors in age and talent, Turner and Constable. Danby's frequent sunsets are usually heavy on the tomato sauce and, like so many of his time, including Agasse, he was also a shameless 'red-blobber'. In their hands waistcoats and coats, kerchiefs and blankets join the more familiar roseate Shawls and bonnets in a common striving for easy pictorial effects. In the last analy- sis, that tempting touch of red is the mark of the tradesman.

Previous page

Previous page