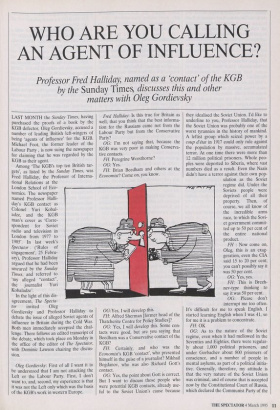

WHO ARE YOU CALLING AN AGENT OF INFLUENCE?

Professor Fred Halliday, named as a 'contact' of the KGB by the Sunday Times, discusses this and other matters with Oleg Gordievsky

LAST MONTH the Sunday Times, having purchased the proofs of a book by the KGB defector, Oleg Gordievsky, accused a number of leading British left-wingers of being 'agents of influence' for the KGB. Michael Foot, the former leader of the Labour Party , is now suing the newspaper for claiming that he was regarded by the KGB as their agent. Among 'The KGB's top ten British tar- gets', as listed by the Sunday Times, was Fred Halliday, the Professor of Interna- tional Relations at the London School of Eco- nomics. The newspaper named Professor Halli- day's KGB contact as Colonel Yuri Kobal- adze, and the KGB man's cover as 'Corre- spondent for Soviet radio and television in London from 1977 to 1985'. In last week's Spectator . (`Rules of engagement', 25 Febru- ary), Professor Halliday argued that he had been smeared by the Sunday Times, and referred to 'my alleged "contact", the journalist Yuri Kobaladze'.

In the light of this dis- agreement, The Specta- tor invited Oleg Gordievsky and Professor Halliday to debate the issue of alleged Soviet agents of influence in Britain during the Cold War. Both men immediately accepted the chal- lenge. There follows an edited transcript of the debate, which took place on Monday in the office of the editor of The Spectator, with Dominic Lawson chairing the discus- sion.

Oleg Gordievsky: First of all I want it to he understood that I am not attacking the Left or the Labour Party. First, I don't want to, and, second, my experience is that it was not the Left only which was the basis of the KGB's work in western Europe.

Fred Halliday: Is this true for Britain as well, that you think that the best informa- tion for the Russians came not from the Labour Party but from the Conservative Party? OG: I'm not saying that, because the KGB was very poor in making Conserva- tive contacts.

FH: Peregrine Worsthorne?

OG: Yes.

FH: Brian Beedham and others at the Economist? Come on, you know.

OG:Yes, I will develop this. FH: Alfred Sherman [former head of the Thatcherite Centre for Policy Studies'?

OG: Yes, I will develop this. Some con- tacts were good, but are you saying that Beedham was a Conservative contact of the KGB?

FH: Certainly, and who was the Economist's KGB 'contact', who presented himself in the guise of a journalist? Mikhail Bogdanov, who was also Richard Gott's contact.

OG: Yes, the point about Gott is correct. But I want to discuss those people who were potential KGB contacts, already use- ful to the Soviet Union's cause because they idealised the Soviet Union. I'd like to underline to you, Professor Halliday, that the Soviet Union was probably one of the worst tyrannies in the history of mankind. A leftist group which seized power by a coup d'etat in 1917 could only rule against the population by massive, accumulated terror. At one time there were more than 12 million political prisoners. Whole peo- ples were deported to Siberia, where vast numbers died as a result. Even the Nazis didn't have a terror against their own pop- ulation as the Soviet regime did. Under the Soviets people were deprived of all their property. Then, of course, we all know of the incredible arms race, to which the Sovi- et government commit- ted up to 50 per cent of the entire national product.

FH : Now come on, Oleg, this is an exag- geration, even the CIA said 15 to 20 per cent; you can't possibly say it was 50 per cent.

OG: Yes, yes.

FH: This is Brezh- nev-type thinking to say it was 50 per cent.

OG: Please don't interrupt me too often. It's difficult for me to speak English. I started learning English when I was 41, so for me it is a problem to concentrate.

FH: OK OG: As to the nature of the Soviet regime, even when it had mellowed in the Seventies and Eighties, there were regular- ly about 1,000 political prisoners, and under Gorbachev about S00 prisoners of conscience, and a number of people in mental asylums, as part of a political initia- tive. Generally, therefore, my attitude is that the very nature of the Soviet Union was criminal, and of course that is accepted now by the Constitutional Court of Russia, which declared the Communist Party of the Soviet Union a criminal organisation, and the Soviet Union was this Communist Party because it was the only real state structure. My view is that [for a foreigner] to have helped that regime in any way was not nice, not honest, in fact a really reprehensible thing to have done. There was an interest- ing point in your article [in last week's Spectator] about the legitimacy of the Sovi- et regime. Of course there was no legitima- cy whatsoever. There were conditions of terror, total control by the secret police, the KGB.

FH: Excuse me, I didn't say it was legiti- mate. I said most Soviet people thought it was, which is very different.

OG: How could you know that the Soviet people accepted the regime? How can a western academic judge about the legitima- cy of a situation which he would not toler- ate himself for a moment?. . . Now in your article you made a statement about the sin- cerity of people who were saying things which might have been helpful to the Sovi- et Union. I think that the fact that they were very useful to the Soviet Union was in itself a bad thing. You, Professor Halliday, tended to regard the Cold War as a rivalry between two superpowers, without making any moral assessment. Somehow there was a great tendency to ignore all the unpleas- ant facts of the Soviet Union. You, and people like you, spoke of the Soviet Union as if it was just another society, although of course you knew that it wasn't just another society.

FH: I never said this.

OG: But it is the conclusion of what you had been writing.

FH: Just another society? I never wrote that.

OG: All right. You remain with your opinion. I remain with my opinion.

At this point Gordievsky drew attention to the following remarks in Professor Halli- day's article in last week's Spectator, which he had underlined several times: 'It is a fantasy to suggest that there was necessari- ly a connection between talking to Russians and what one wrote, any more than to say that, because in the course of one's investi- gations one visited the State Department one was an agent of "US Imperialism".'

FH: What I am saying is that I hope that by talking to them [The Americans] I was helpful to them.

OG: But helpful to the KGB as well.

FH: Not to my knowledge.

OG: That's what I don't believe at all.

FH: You think I'm lying? Let's be clear about this. I don't mind, but if you think I'm lying, say I'm lying.

OG: No, I'm sure you knew Kobaladze [Halliday's KGB 'contact' according to the Sunday Times; 'a journalist' according to Halliday in last week's Spectator] was in the KGB. You may deny it but I think it's impossible that a person of your back- ground can be so naive.

FH: I've met agents in my time, and they didn't behave like Kobaladze. First of all..

OG: Stop!

FH: All right.

OG: I must say what I'd like to say. Kobaladze was your good contact, and you were a good contact of Kobaladze. Yet you have so little here [points to Halliday's arti- cle in The Spectator] about Kobaladze. The information about Kobaladze is conspicu- ous by its absence. I find that very strange because it would have been the most inter- esting thing to read about. Why do you think there is such a long and thick KGB file on you? And reports of meetings? Did you influence Kobaladze, or did he influ- ence you? Either is possible. Kobaladze liked you very much, and he liked your knowledge, but if, for example, the Foreign Office had taken you, and put you in the press department, or any department what- ever, he would have been ten times happier than he was. Because really the KGB want- ed not the influence as such, but the intelli- gence.

FH: But you know I wasn't a prominent person; I didn't even have a university post at the time.

OG: It was your general knowledge he wanted.

FH: But the Sunday Times implied that this was penetration of the academic world, and I wasn't even in the academic world at the time.

OG: All right, but this is splitting hairs, because the point is that you were valuable for Kobaladze as a person of great knowl- edge, particularly of the Middle East.

At this point Gordievsky again pulled out his copy of Professor Halliday's article, and pointed to the section in which Halliday referred to him as sounding 'like the secret policeman he once was' in describing inde- pendent critics of the arms race as Soviet agents of influence.

OG: So, you say my thinking is like a secret policeman?

FH: Sometimes.

OG: OK, I will call you the secret KGB informer. But I will not do it, and I will be precise. While you defend yourself, you resort to abuse in calling me a secret policeman, which I don't like.

FH: The KGB is a secret police.

OG: Of course.

FH: You were a member, so you were a secret policeman, till you changed sides.

OG: But from the early 1970s I was working for the British.

FH: Fair enough OG: I was a British intelligence man.

FH: Look, I think that you played an important role in reducing tension and in bringing the Cold War to an end. But now can I ask you something? You've seen all these reports of my discussions with Kobal- adze. Is there anything that you've seen that I'm reported as saying that you would regard as improper, indiscreet or careless? Something I should not have said?

OG: In a few situations when Kobaladze was asking about the Arabian Gulf area, Afghanistan, Iran, Iraq. There were a num- ber of situations in which he was asking you for advice. What would be in the best inter- ests of the Soviet Union? What measures or steps ought to be taken? And according to Kobaladze, your answers were sympa- thetic, giving recommendations through him to the Soviet leadership, which Kobal- adze then dictated or wrote some pieces about for our professional analysts. There were some very clever analysts at the KGB station in London. I supervised the work. The analyst would be sitting there writing the reports and in the end he would put forward your recommendations, or alleged recommendations, which went on to Moscow. This was the only thing which I regard as undesirable, if it was true.

FH: It worries me, and I say this as a British citizen, it worries me that I might have said something improper or careless. My memory is, one, we hardly ever talked about Britain, and two, that I didn't say anything which wasn't in the public domain, broadly speaking. Maybe I made a mistake. You tell me. You have the evi- dence. Did I say anything that was care- less?

OG: No, it's what I've said, that's all.

FH: OK, fine.

OG: The fact was that, of course, I was realistic enough to see there was nothing sinister in your relationship and it is one of those cases that you understand very well, one of those whose importance is obviously exaggerated.

At this point Halliday reached out across the table and offered his hand to Gordievsky, who shook it. A most touching scene.

The discussion then moved on to the question of the western movements for nuclear disarmament, some of whose mem- bers Gordievsky has categorised as Soviet agents of influence, but who are described by Professor Halliday as sincere, indepen- dent and truthful. Dominic Lawson asked Gordievsky whether he agreed that it was possible to have been a member of the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament with- out being termed an agent of influence for the Soviets.

OG: I never claimed that there was a direct penetration of the CND by the KGB.

Though what I would say is that indeed the CND people were very much in touch with the Soviet Embassy here, consulting with the Ambassador and his aide who was responsible for the international depart- ment. The CND was not even-handed.

They criticised the West much more than they did the Soviet Union. There was a group led by Lord Brockway [Labour MP and later peer, who died in 1988] who were listening to Moscow all the time, and in most cases doing what they were told.

Dominic Lawson: Oleg, are you saying that Fenner Brockway personally took advice from Soviet agents on how to carry out his campaign?

OG: From the KGB.

DL: And he knew that?

OG: He took their advice, whether he knew the man in question was KGB or just a Soviet official. I don't want to go more into it because it is very complicated.

DL: But it is interesting, because Fenner Brockway was thought of as a cuddly old man.

OG: Yup, yup, sometimes it was a weekly contact between him and the KGB officer.

FH: Oleg Antonovitch, I think you are jumping to conclusions. They are ones I cannot possibly accept. There are people who knowingly perpetrated Soviet lies. But there are also people who talked to the Russians, and that's another matter. . . My broader point is that despite the fact that you worked for the British for a long time and have lived here, you still have too con- spiratorial and black-and-white view of pol- itics, and here you are helping people, unwittingly I think, to corrupt public life in this country. And I think that the Sunday Times article ['With smiles and cash: how the KGB targeted Labour leaders', 19 February] was a good example of this. It was accompanied by an extraordinary range of photographs. There were these nine Labour worthies and then me. And it said on top that we were the top ten KGB targets in Britain. I find this preposterous . . . Now I can think of ten important peo- ple but they weren't those named by the Sunday Times. Let me name them. Sir Alfred Sherman was in contact with Arkady Maslennikov of Pravda. Sir Antho- ny Kershaw [former chairman of the For- eign Affairs Committee of the House of Commons] would have dinner at the Soviet Embassy. Brian Beedham, and others at of the Economist saw Mikhail Bogdanov, who was Richard Gott's controller according to the newspapers . Peregrine Worsthorne, Woodrow Wyatt. . . in that kind of list, and there must be many others, was I one of the top ten KGB contacts?

OG: Why not? You were a promising young man. You were a very good choice. FH: But compared with Peregrine Worsthome?

OG: Worsthorne's articles were not regarded as making a great impact.

FH: What, not more than pipsqueak Hal- liday's?

OG: But he was not promoting the Sovi- et cause.

FH: Was I promoting the Soviet cause? OG: Or the KGB under the influence of Kobaladze's thoughts.

FH: Show me a single sentence where I promoted the Soviet cause. Why was I denounced by the World Marxist Review, the official organ of the Communist move- ment, as anti-Soviet?

Dominic Lawson: I think that Fred's gen- eral point is that the selectivity, as he sees it, of the Sunday Times's disclosures has created the dangerous impression that British intelligence has somehow become involved in political battles against the Labour movement specifically. Could you respond to that? OG: The intelligence and security organ- isations of this country have nothing to do with it, and are probably unhappy about it. I am sorry about that; I don't want to hurt them. On the other hand, when writing about the KGB's work in Britain it would be stupid not to illustrate cases with names. But I expected that if some of the names would be regarded as offensive then the lawyers would stop it, as I told both the publishers and the Sunday Times. DL: What do you mean by 'offensive'? OG: Offensive in legal terms.

DL: Wrong? OG: In legal terms, libellous.

DL: Wrong? OG: If it's libellous, then it's wrong. But I understand that the Sunday Times's entire legal department had been consulted for weeks and weeks.

DL: But now Michael Foot is suing the Sunday Times. You seem to be saying, `Well, I put in Michael Foot's name. It's up to the Sunday Times to check whether that is libellous.' Surely it was up to you to know whether or not it was true.

OG: Yes, and I am absolutely sure that everything I said in the book is true. If I know too little I don't say it.

DL: Are you happy that the Sunday Times has not misinterpreted what you said in your book? OG: I am under a total ban against mak- ing any statements or even indirect com- ments about the Foot case.

FH: Kobaladze once said to me that the biggest mistake of the Soviet Embassy in this country was to cultivate communists.

They should have been cultivating the real ruling power, which is the Tory party. And his great hero was Bernard Ingham [Mrs Thatcher's former press spokesman]. He just regarded this man as a miracle worker of manipulation.

OG: The Embassy cultivated the British communists because it had to. It was a direct order from the Central Committee. Apart from that, yes, I absolutely agree that the main target was the Conservative Party. I was sent to this country to pene- trate and cultivate the Conservative Party.

DL: And here you are. You've done it.

FH: I would say that the current alarm is not that the security services are whipping up this attack [on the Labour movement]. I don't think they are. But they have been incompetent in the way they have handled it.

OG: No, this is not true. They haven't handled it at all.

FH: They have mishandled it.

OG: Are you saying they should have put me under house arrest?

FH: Mr Gordievksy, I am a citizen of this country, and a taxpayer. I am paying your pension, and I object to the fact, strongly object to the fact, that the information which you have gathered has been allowed by somebody to be so misused, so as to wage a partisan political campaign by sec- tions of the press. I am not in favour of your pension being cut off. But heads should roll.

OG: You are asking me to shut up. Other than house arrest, there is no other way. As to my pension, which you raise: the fact is that it was my co-operation with the British security and intelligence services which saved this country millions and mil- lions of pounds. My pension, which is less than £20,000 a year, is a tiny, tiny part of the huge amount of money I saved. And I do not wish, as you claim, to undermine democracy in this country.

FH: Then criticise the Sunday Times.

OG: No, I can't criticise the Sunday Times.

FH: Why not?

OG: Because it would be disloyal. I gave them my manuscript, or rather my agent did.

FH: They are sleazeballs, they are muck- rakers. Printing calumnies to make money.

OG: The Sunday Times? But look at all the abusive and offensive articles the Inde- pendent and the Guardian have written about me.

FH: The Sunday Times, to quote Tolstoy: Podayut yevo kak sterlyat' . They serve you up like a fish. They eat you up and throw away the bones. They have done it to Princess Diana, and now they will do it to you.

Previous page

Previous page