A WASTE OF GOOD CELLULOID

Public money and professional wailers have ensured that Britain has a derisory film

industry, says Alexander Walker IN Hollywood, if you want to make a film, you go to the bank. In Britain you go to the bureaucrats. That is why the Americans still have the world's biggest movie industry and why we still have Lord Puttnam. Yes, we make individual films that win prizes and make big money: A Fish Called Wanda, The English Patient, Shakespeare in Love, Notting Hill, The End of the Affair. But these are funded by the Americans and it is they who take the money home.

Since 1995, we have ploughed £92.6 mil- lion of National Lottery cash into our native film-making. Wasted, most of it. Not one British film has benefited from this kind of subsidy and then made it into the top category of Oscars. This year the Oscar voters have nominated five of their own all- American kind as 'Best Picture', relegating the British film, Mike Leigh's Topsy-Tuny (£2 million of Lottery money in a £13.5 million budget), to the technical 'award cat- egories. Oh yes, I almost forgot: a small British Lottery-aided film, Solomon and Gaenor (n86,000 of public money out of a £1.6 million budget), got into the 'Best For- eign Film' category — 'foreign' because its characters spoke Welsh and Yiddish. And that's it. Those are the returns from the extravagant investment of public money in British film-making. Our reward has gener- ally been the worst of both worlds: no art and no box-office.

A derisory £5 million has to date been recouped by the Arts Council of England (ACE). That is the entire yield generated by the 25 state-sponsored films that actually made money. In many cases the pittance they have handed back is the last that ACE will see of its investment. The money is earned on 'first sale' abroad, usually to an American distributor, and often the only sale that can be kept track of in an industry that has historically sought to produce income, not profit (for the benefit of non- accountants: income can be stolen, whereas profit has to be declared).

We, the taxpayers and credulous Lottery players, are fortunate to know these sham- ing figures, sketchy though they are. ACE arrogantly refuses to say which films are the losers — and by how much — and which the modest winners, on the grounds that such information is 'commercially sen- sitive'. In other words, the spending of public money is transparent when it's awarded to a film. It then grows opaque while it's being spent on the film. And finally it becomes inscrutable when the film gets shown — if it ever does.

As in the Common Agricultural Policy, over-funding has resulted in overproduc- tion. Films fust on shelves till their com- mercial freshness has gone. If they are eventually 'released', it's often a token release — in a half-dozen shoe-box cine- mas — mainly to qualify them as 'theatri- cal' films, so that they are eligible for a smidgen more of what is ultimately our money when sold on to television or video.

The process is not profitable. It is not accountable. And it produces rubbish. Cash does not buy quality and public cash buys even less of it. The incentive to pay the money back — the alternative, in a normal limited company, is called bankruptcy — is absent when 'soft' loans are disbursed as public patronage.

What Chris Smith and others fail to understand is that films are not normal business. They are a gamble, a bet, a wager on 'expectations': irrational, unsafe, often wildly extravagant, difficult to keep tabs on, frequently enriching the rogues and rascals who have flocked to the Lottery feeding trough with no credentials but their chutzpah. That is why film-making is totally inappropriate for public investment, at least on the present scale. And yet that scale is expanding.

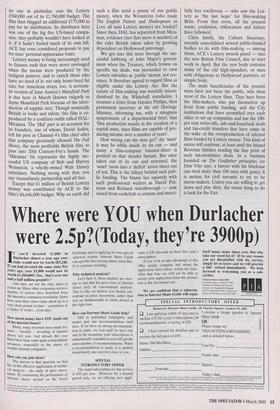

These days, the bludging British produc- ers can even get the Lottery to stump up for the cost of their celluloid prints and adver- tising. Hold Back the Night, a very ordinary, poorly received little 'road' movie, starring no one in particular, cost the Lottery £560,000 out of its £1,760,000 budget. The film then blagged an additional £175,000 to pay for its distribution. Its distributor here was one of the big five US-based compa- nies: they probably wouldn't have looked at it, if it hadn't footed much of its own bill. ACE has even considered proposals to pay for stars' personal-appearance tours.

Lottery money is being increasingly used to finance ends that were never envisaged when the means were produced by the indigent punters, and to enrich those who have no need of it: not only home-bred fat cats, but American strays, too. A revision- ist version of Jane Austen's Mansfield Park is due here in March (known vulgarly as Jayne Mansfield Park because of the intro- duction of sapphic sex). Though nominally British in looks and talent, this film is co- produced by a coalition outfit called HAL- Miramax. The 'Hal' part is an acronym for its founders, one of whom, David Aukin, left his post as Channel 4's film chief after that company graciously allowed The Full Monty, the most profitable British film, to pass into 20th Century-Fox's hands. The `Miramax' bit represents the highly suc- cessful US company of Bob and Harvey Weinstein, a wholly-owned Walt Disney subsidiary. Nothing wrong with that, you say: transatlantic partnership and all that. Except that £1 million of British Lottery money was contributed by ACE to the film's £6,646,000 budget. Why on earth did such a film need a penny of our public money, when the Weinsteins (who made The English Patient and Shakespeare in Love all sans Lottery money) are loaded? Since then, HAL has separated from Mira- max, evidence (not that more is needed) of the risks British talent takes by growing dependent on Hollywood patronage.

We got into this mess through the suc- cessful lobbying of John Major's govern- ment when the Treasury, which frowns on specific tax deals, was persuaded to view Lottery subsidies as 'public' money, not rev- enues. It therefore agreed to regard films as eligible under the Lottery Act. But the nature of film-making was woefully misun- derstood by the Whitehall mandarins. I treasure a letter from Hayden Phillips, then permanent secretary at the old Heritage Ministry, informing me, with a smugness symptomatic of a departmental brief, that `film production results in the creation of a capital asset, since films are capable of pro- ducing income over a number of years'.

How wrong can the man get? An 'asset' it may be while inside its tin can — and many a film-company balance-sheet is posited on that slender fantasy. But once taken out of its can and screened, the `asset' turns into a 'deficit' seven times out of ten. This is the fallacy behind such pub- lic funding. The blame lies squarely with such professional wailers as David Put- tnam and Richard Attenborough — now raised from sackcloth to ermine and merci- fully less vociferous — who saw the Lot- tery as 'the last hope' for film-making Brits. From that error, all the present waste, confusion, obfuscation and failure have followed.

Chris Smith, the Culture Secretary, recently consolidated several public-funded bodies to do with film-making — among them, ACE's Lottery awards panel — into the new British Film Council, due to start work in April. But the new body contains many of the old high-spenders, or men with obligations to Hollywood partners, or simple fools.

The main beneficiaries of the present mess have not been the public, who shun most of the Lottery films. They have been the film-makers, who pay themselves up front from public funding, and the City institutions that have scrambled over each other to set up companies and use the 100- per cent write-offs, sale-and-leaseback deals and tax-credit transfers that have come in the wake of the overproduction of inferior films funded by Lottery money. This kind of excess will continue, at least until the Inland Revenue finishes reading the fine print of such tax-avoidance deals. In a business founded on The Godfather principles (as Don Vito says, a lawyer with his briefcase can steal more than 100 men with guns), it is useless for civil servants to try to be movie-makers. Unless you are willing to get down and play dirty, the wisest thing to do is look for the Exit.

Previous page

Previous page