HOPELESS IN GAZA

Ian Buruma reports on the

wretched ghetto at the heart of the Palestinian diaspora

Jerusalem AS I was driven through the filthy streets of Gaza, where children rooted through stinking piles of refuse and young men hung around the shuttered shops waiting for trouble to erupt, I kept wondering why anyone would want to hang on to this place. The Gaza strip, 'home' to roughly half a million Palestinian refugees from the 1948 war of Israeli independence, is one of the territories that the Palestinians would take over if they were to get their own state. It wouldn't be much of a state, really, Gaza and the West Bank, but to a dispos- sessed people it would seem a lot better than nothing.

Even if Israel were willing to return Gaza, few Israelis wish to lose the West Bank, for sen- timental and strategic reasons. But Gaza alone would not satisfy the Palestinians.

Until the war of 1967, Egypt ruled Gaza bru- tally, in the way back- ward little colonies were ruled in the 19th cen- tury. Israeli govern- ment, after 1967, was more benign and the local economy improved. But the political violence never stopped. Israel offered to hand it back to Egypt in 1979, but Egypt refused. The Palestinians whom nobody wanted were Israel's problem. The Israeli writer Amos Elon, in his book The Israelis, quoted an Israeli-Arab writer's description of Israel's plight: 'Instead of stepping on the snake that threatened them, they swal- lowed it. Now they have to live with it, or die from it.'

Gaza is where Samson, betrayed by the Prostitute Delilah, and blinded by the Philistines, pulled down the pillars of the Philistine temple. Gaza is also where 5,900 British soldiers died in 1917, when they tried to take it from the Turks. Gaza is where the Palestine Liberation Army was set up with Egyptian help; where fedayeen planned their raids into Israel to terrorise Jewish settlers; and where the PLO was formed. Gaza is also where the intifada began, on 8 December 1987, when four local residents were killed in a crash with an Israeli car.

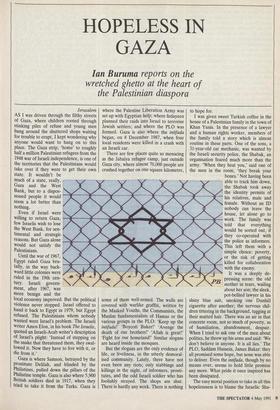

There are few places quite so menacing as the Jabalya refugee camp, just outside Gaza city, where almost 70,000 people are crushed together on one square kilometre, some of them well-armed. The walls are covered with warlike graffiti, written by the Masked Youths, the Communists, the Muslim fundamentalists of Hamas or the various groups in the PLO: 'Keep up the intifada!' Boycott Baker!' Avenge the death of our brothers!' Allah is great!' 'Fight for our homeland!' Similar slogans are heard inside the mosques.

But the slogans are the only evidence of life, or liveliness, in the utterly demoral- ised community. Lately, there have not even been any riots; only stabbings and killings in the night, of informers, prosti- tutes, and the odd Israeli soldier who has foolishly strayed. The shops are shut. There is hardly any work. There is nothing to hope for.

It was a deeply de- .P_B pressing scene: the old mother in tears, wailing about her son; the sleek, pot-bellied lawyer in his shiny blue suit, smoking one Dunhill cigarette after another; the nervous chil- dren tittering in the background, tugging at their matted hair. There was an air in that concrete room, not so much of poverty, as of humiliation, abandonment, despair. When I tried to ask one of the men about politics, he threw up his arms and said: 'We don't believe in anyone. It is all lies.' The PLO, Saddam Hussein, James Baker: they all promised some hope, but none was able to deliver. Even the intifada, though by no means over, seems to hold little promise any more. What pride it once inspired has been dissipated.

The easy moral position to take in all this hopelessness is to blame the Israelis: Sha- mir's pig-headed intransigence; the brutal- ity of some of the security forces; Ariel Sharon's perverse insistence on building more Jewish settlements, which are like bits of Western suburbia floating like islands in a sea of squalor, their evident prosperity acting as an extra taunt to the Palestinians. (The presence of Israel itself has a rather similar effect in the Middle East as a whole.) What makes the humilia- tion worse is that many Palestinians, partly thanks to UN programmes, are rather well educated. But the universities are closed, and they have nowhere to go.

Liberals in Tel Aviv and Jerusalem blame their own government and even themselves for the Palestinian plight. A distinguished professor, who survived Au- schwitz, told me one can compare Israel today to Germany in 1936. He didn't mean the respective regimes, which are not comparable, but the indifference of most people to the suffering in their midst. Gaza is indeed like a large ghetto, where no Jew, outside the army or the well-protected settlements, would set foot.

I asked the commander of the Israeli Defence Forces battalion what he thought of Sharon's building programmes in the occupied territories. We were driving in a jeep through the Jabalya refugee camp, very slowly, avoiding schools and mosques to minimise provocation. People watched us carefully, as we rolled by. I have never seen faces filled with such hate. 'Sharon,' said the commander, who was an engineer in daily life, 'is crazy!' The IDF spokes- man, a nervous public-relations type, told his superior officer that soldiers were not allowed to make political statements. The commander said nothing for a bit, then leaned over to me with a broad smile: 'OK, OK, my mother thinks Sharon is crazy!'

The Israeli reserve soldiers whom I met in Gaza, decent, polite, well-educated men, made little attempt to hide their loathing of having to police up to 750,000 embittered Arabs. This ghastly situation clearly isn't their fault. But then neither is the Israeli government wholly to blame for what happened in Gaza. The problem is too complex to blame it on any one party. Egypt, Israel, the Palestinians themselves, have all contributed to the mess. In a way, the intifada is like a suicide attempt by an abandoned person who wants to attract attention. It is getting harder and harder to cross the 'Green Line' to find jobs in Jewish areas. Jewish employers are fearful and the security is tighter. The Palestinian boycott has destroyed small businesses in the territories, where all shops have to close in the afternoons. Tourism is virtually non-existent, even in places that used to attract many visitors, such as Bethlehem. Even the menial jobs in Israel are being filled by Soviet immigrants or imported Rumanian workers.

'The Arabs are making a big mistake,' said one of the soldiers in Gaza, a compu- ter programmer in civilian life. 'They could do very well in our economy. I wish they did, for it would be better for us if they had something to lose.' I was reminded of a Palestinian bazaar merchant in the Old City of Jersualem, who had made a similar point about the Kurds. They had no right to rebel against Saddam Hussein, he said. 'Instead of stabbing him with a knife, they should say "thank you, Saddam". He gave them radio, television, cars . . .' Few Palestinian tears are shed for the Kurds. And one can still hear excuses being made for Saddam, the hero who stood up to half the world.

The Palestinian problem is, of course, not just economic. Prosperity is being deliberately sacrificed to serve a political ideal, an independent Palestinian state. This makes it harder to put all the moral blame on Israel. There are too many Palestinian murders of Palestinians for that.

There is something eerie about the way Palestinians, in public at least, claim that elections would be useless, since 'the PLO are our only leaders'. This is partly a matter of pride, to be sure. The more Israel insists on ignoring the PLO, the more Palestinians proclaim their loyalty to it. But there is also the fear of proclaiming anything else. There is something naive, too, about the insistence that statehood and freedom are always identical. Nor is it at all clear that the interests of the Palesti- nians living in the occupied territories are identical to those of the entire Palestinian diaspora. But to make a distinction is regarded by the PLO leaders in Tunis as betrayal of the Palestinian cause.

It was refreshing, after days of listening to PLO rhetoric, to hear something very different from a Palestinian acquaintance who drove me to Bethlehem. He was in his forties, spoke good English, and had spent a year in America. He held Israeli as well as Jordanian citizenship. But the Jorda- nians were so cross about his having travelled to the United States on his Israeli papers that they insisted on his coming to Amman to renew his Jordanian passport. This he was loath to do: 'At least in Israel, you can get a lawyer. Things can be done here. In Jordan I might just disappear.' I asked him what he thought of Yasser Arafat and the PLO. 'Arafat,' he said, without a moment's hesitation, 'sits on the beach with girls, makes lots of money. He doesn't want anything to change. If I were the leader, I would sit down with Israel, with six Palestinians on one side and six Israelis on the other, and make peace. Then we could all make a good living again.'

The assessment of Arafat may be inaccu- rate — in fact, Arafat works very hard and girls are not a conspicuous feature of his life — but my friendly driver is apparently not alone in his views. Doubts about the leadership of the PLO, which were totally taboo before, are drifting to the surface. Like any large bureaucracy with a monopoly of power it is quite corrupt. Money has a way of ending up in the wrong, already well-stuffed pockets. I was told how Palestinians in a refugee camp complain about corruption in the PLO and openly debate its policies, something un- heard of before. It is impossible to tell how widespread this is. But disillusionment after the debacle in Iraq, with which the PLO associated itself, has cast doubts on the Palestinian leadership. And suddenly the PLO has the added problem of being starved of ready cash, now that the Saudis are refusing to lend financial support.

All this would appear to suit the Israeli government, as well as Washington, since both refuse to negotiate directly with the PLO. Israel is only willing to talk to local representatives, outside East Jerusalem and independent of the PLO. But despite the PLO's present troubles, this remains an impossible demand. The Palestinians who talked to James Baker in Jerusalem were in fact local figures, mostly from grand fami- lies, with strong connections with the PLO. It cannot yet be otherwise, for no matter what one thinks of the leadership in Tunis no Palestinian can represent his people without PLO support. At best such a person would lack credibility, at worst he would be killed.

There is, however, an alternative to the PLO which is hardly an improvement: Hamas, the Muslim fundamentalist move- ment. As life in the territories grows more desperate and a political solution appears more distant by the day, the influence of Hamas, with its utopian dreams of a Muslim state, grows apace. In the Gaza strip I was told that Hamas already has the support of more than half the people. This is deeply disturbing to secular Palestinian politicians, which is why leftists and com- munists connected with the PLO are des- perate to have peace talks. They want a conference in which Palestinian self- determination can be discussed without preconditions. Without such a conference they are afraid of losing what influence they have and of the mullahs taking over. As long as self-determination is accepted as the ultimate aim, there appears to be flexibility as to what should precede that aim, enough at any rate to talk about. A long period of autonomy in the territories is one possibility. The problem is getting Israel to negotiate. James Baker has already indicated that he is unwilling to force the Israelis to do so.

Fear of Hamas is one reason why PLO representatives in the Israeli territories are weary of having elections. They might lose. Yet elections, as Shamir has suggested, would be one way of testing the legitimacy of Palestinian representation. It would turn the PLO, or, indeed, Hamas into elected political parties instead of authoritarian movements. The problem here is again Israel, which won't allow the PLO to take part in elections. And as long as Washing- ton remains unwilling to put more pressure on Israel, such elections won't take place.

The other obstacle to compromise is the Israeli electoral system. Proportional rep- resentation means that small right-wing or religiously extreme parties hold the ba- lance in coalition governments. Some of these parties are only interested in domes- tic matters, but some, such as Tehiya (Ba'ath in Arabic), wish to expel the Arabs. This means that Shamir can go on refusing to trade any land for peace, and Sharon can continue building his settle- ments on conquered land. And it explains why, last week, Shamir turned down the American proposal for open-ended peace talks, favoured by his foreign minister but anathema to the marginal extremists. Most Israelis who are neither religious zealots nor political extremists just want to be left in peace.

Israeli liberals who express sympathy for the Palestinians are branded in the right- wing press as traitors. I picked up a pamphlet in my hotel of the Torah Out- reach Program, which is supported by the Jewish Agency. Its language echoed that of editorals I had read in the Jerusalem Post. About Jewish Peace Now activists oppos- ing a new Jewish settlement in the Old City of Jerusalem: . . self-proclaimed fighters for democracy [are] de facto fascists, proc- laiming Hitler's doctrine of Judenrein, that Jews may not live among other people.' Last week, the defence minister, Moshe Arens, compared the idea of trading land for peace with doing a deal with Hitler. It is undeniable that Israel faces risks in nego- tiating about land with so many hostile people, but using Nazi rhetoric (luden- rein' is a favourite) to manipulate public Opinion not only cheapens the memory of Jewish suffering, it also debases the politic- al debate, making a sensible solution more difficult.

The tragedy is not just that Israel and the Palestinians are unlikely to come to an agreement under the present circumst- ances, but that moderates on both sides are abused and silenced. The soldiers I met in Gaza and my driver to Bethlehem were not nearly so far apart as the leaders who represent them. One of the IDF soldiers gave me a lift out of Gaza. He said he was in favour of giving back the land to the Palestinians. To continue to occupy it, he said, was a waste of time and money. We crossed the checkpoint that separates the Gaza strip from the neat, prosperous, green valleys of Israel proper. The soldier stopped the car and unclipped the extra windshield, which was there to protect us against Palestinian stones. 'We are in Israel now,' he said. 'We won't be needing this here . . . not yet.'

Previous page

Previous page