HE FLIES THROUGH THE AIR . . .

William Cash reports on the latest

human projectile experiments, which involve flying pigs

I WROTE in the Spectator Christmas issue on the exploits of the eccentric Shropshire inventor Hew Kennedy, builder of a 60ft mediaeval siege engine for catapulting pigs and pianos into orbit. Since then, Mr Kennedy's fame has spread to the pages of a Melbourne newspaper and interest in the project has been shown by a government weapons scientist and the US space prog- ramme. Now that the next phase of the experiment is under way — using a live human as a projectile — a progress report is in order.

Launching a man into space with a 14th-century siege engine — or trebuchet — ranks as easily the most ambitious scheme of Mr Kennedy's investment career. This has most recently included fashioning a ready-to-wear suit of arrow- proof African elephant armour in the old dining room of his Queen Anne mansion near Bridgnorth. Sitting in his kitchen, ominously wallpapered with newspaper stories of people who met unfortunate ends, he explains the major worry of his plan. 'Catapulting off humans is nothing new,' he says; 'in the Middle Ages they were always sending ambassadors back over castle walls: bringing someone down alive in a parachute is another matter.'

On a cold and misty Saturday earlier this month a trial took place in a soggy Shrop- shire field. The sheep who share the 20 acres with the 30-tonne siege engine have become shrewdly expert at avoiding the crater-sized bunkers made by the impact of Projectiles crashing to earth. Spending the night inside one is not recommended. After heavy rain, they turn into watery Pot-holes with blobs of buried viscera floating on the surface.

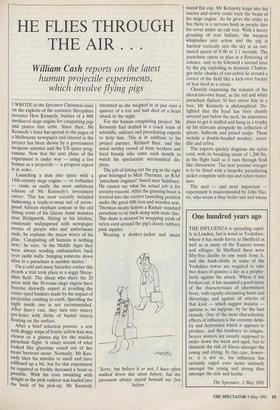

.After a brief selection process, a sow With shaggy wisps of bristly yellow hair was chosen as a guinea pig for the maiden Parachute flight. A runny stream of what looked like glycerine oozed out of her moist beetroot snout. Normally, Mr Ken- nedy likes his missiles to smell and have Stiffened up a bit, but for this experiment he required as freshly deceased a beast as Possible. With his eyes twinkling with delight as the pink cadaver was loaded into the back of his pick-up, Mr Kennedy informed us she weighed in at just over a quarter of a ton and had died of a heart attack in the night.

For the human catapulting project, Mr Kennedy had drafted in a crack team of scientific, military and parachuting experts to help him. This is in addition to his project partner, Richard Barr, and the usual motley crowd of farm workers and local friends who come each month to watch his spectacular aeronautical dis- plays. The job of kitting out the pig in the right gear belonged to Mick Therman, an RAF 'parachute engineer' based near Salisbury. He cannot say what his actual job is for security reasons. After the grinning beast is levered into the correct launching position under the great 60ft iron and wooden arm, Therman neatly fastens a Ramair standard parachute to its back along with static line. The chute is secured by wrapping yards of nylon cord around the pig's dozen rubbery pink nipples. Wearing a donkey-jacket and smart 'Sorry, but believe it or not, I have often walked down this street before, but the pavement always stayed beneath my feet before.' tweed flat cap, Mr Kennedy leaps into his tractor and slowly cocks back the beam of his siege engine. As he gives the order to fire there is a nervous hush as people dart for cover under an oak tree. With a heavy groaning of iron ballasts, the weapon whiplashes into action and the pig is hurtled vertically into the sky at an esti- mated speed of 0-90 in 2.1 seconds. The parachute opens to plan in a flowering of colours, only to be followed a second later by the pig exploding in dramatic Challen- ger style: chunks of raw debris lie around a corner of the field like a kick-over bucket of lion food in a circus.

Cheerily examining the remains of the sliced-into-two beast, as the red and white parachute flutters 50 feet above him in a tree, Mr Kennedy is philosophical. De- lighted that the head has been cleanly severed just below the neck, he announces plans to get it stuffed and hung as a trophy up his staircase alongside his collection of spears, halberds and prized scalps. These include a double-headed monkey, croco- dile and zebra.

The experts quickly diagnose the nylon cord, with its breaking strain of 1,200 lbs, as the flight fault as it runs through flesh like cheesewire. The next porcine voyager is to be fitted with a bespoke parachuting jacket complete with zips and velcro faster- ners.

The next — and most important — experiment is masterminded by John Har- ris, who wears a blue boiler suit and whose moustache gives him a striking resembl- ance to H. G. Wells. He works as a government weapons engineer and tester near Salisbury. Appointed to the job of calculating the G Force experienced when a man is catapulted off the machine, he has spent weeks inventing a unique trebuchet accelerometer which fits snugly in a cham- ber inside a 12-stone log (the weight of the human volunteer, of which more later).

Putting his hand inside a paper toyshop bag, he pulls out a green rubber bouncy ball the size of a squash ball. He explains how, by squeezing it inside a paper-lined small plastic box and adding a few drops of blue ink, he can measure the force of acceleration by the diameter of the post- flight smudge marks. 'Similiar government equipment,' he assured me, 'would cost at least f50,000.'

Following the first log launch, the grey- haired British government scientist had to climb 40 feet up a tree to retrieve his accelerometer after the parachute was blown off course by a gusty Welsh head- wind. The second flight, however, saw a text-book launch, parachute opening and landing. Having now spent nearly 20 hours calibrating the results of the smudged piece of paper with a spring balance and done a separate test using electronic video analy- sis, he estimates the G Force to be between 14.5 and 20G.

Dr Jeffrey Davis, Nasa's chief medical operations officer at the Johnson Space Centre, Houston, Texas, said that whilst such acceleration forces are very high — astronauts in the Space Shuttle experience less than 3G — they would not necessarily kill or even harm a man. When fighter pilots eject from their aircraft in an emergency, for example, they endure be- tween 18 to 20G, although for only a short time. In the 1950s Eli Seeding Jr tolerated 82.5G on a water-braked rocket sled at Holloman Air Force Base, New Mexico. He was in hospital for three days.

The problem for Hew Kennedy's astro- naut is knowing exactly how long the peak G Force will last. If it is sustained for more than about a second there could be a rupture of blood vessels and soft body tissues, high stress on the cardio-vascular system and the eyes may pop out. When the racing driver David Purley experienced 179G after crashing at Siverstone in 1977, his heart stopped six times. Wearing a pressurised 'G suit' will help to reduce the effects, but ideally a way needs to be found to diminish the siege engine's overall veloc- ity.

Mr Kennedy has, apparently, already found a volunteer keen to be the first human projectile to be launched from the siege engine. Daredevil parachutist Mike McCarthy, a 30-year-old veteran of the Falklands campaign, is well suited to the unusual mission as he already holds the world record for a low-level jump of just 179 feet, after leaping off the Leaning Tower of Pisa in 1988. The British Para- chute Association says that parachutes should be open by 2,500 feet.

Having also launched himself off the Eiffel Tower, 600 feet down the Grand Canyon and smuggled a parachute under his raincoat to plunge from the 86th floor of the Empire State Building (fined $86 for landing on top of a Fifth Avenue traffic light), McCarthy is one of the few men in `I'll take it.' the country whose bizarre exploits can compare with Kennedy's own. McCarthy told one interviewer after his Pisa jump, 'You appreciate life. You realise — urrhh — it's such a good thing to be alive.'

In case the flight is successful, Hew Kennedy has already assembled a list of priority passengers. The idea is to make the trebuchet practical in the 20th century. Originally used in the 14th century for propelling frauds into the village pond seated in a bucket, Kennedy now wants to strap down the Lloyds Members agents he says are responsible for losing his family fortune and catapult them head-first into the local River Severn. Only this time, he says, he will not worry about parachutes.

William Cash writes for the Times

Previous page

Previous page