CHESS

Smash and Grob

Raymond Keene

That talented International Master Michael Basman has just produced a book on his favourite opening system, 1 g4 as White and 1 . . . g5 as Black. Titled The Killer Grob (Grob was a Swiss master active in the 1930s), the book catalogues Basman's successes against a variety of grandmasters, international masters and enthusiastic amateurs. For the free spirit there are many refreshing ideas which might help to unclog the arteries of anyone who felt that his or her play was becoming over-bookish. Objectively, though, the Grob strikes me as a dubious proposition, weakening as it does the practitioner's kingside pawn structure as well as a num- ber of key squares in the vicinity of the 'g' pawn. Personally, I always believed that Basman could have developed his talents more effectively had he stuck to conven- tional openings for most of his games and when I played him my main worry was that he would not play 1 g4. Still, The Killer Grob (Pergamon £8.95) is well worth reading for those who wish to refresh their creative urges. I now give one of my own games with Basman, one that curiously eluded publication in full in his book.

M. Basilian — R. Keene: Benedictine, Manches- ter 1981; Grob's Attack.

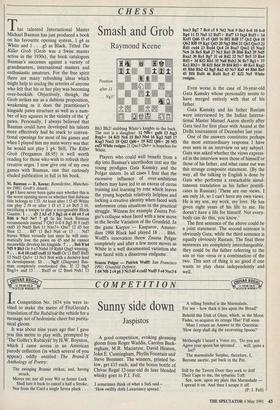

1 g4 I have never been quite sure whether this is the worst opening move or whether that dubious title belongs to 1 f3. At least after 1 f3 d5 White can play 2 f4 or after 1 f3 e5 2 e4 Bc5 3 f4, sacrificing a tempo to play a recognisable Black Gambit. 1. . . d5 2 h3 e5 3 Bg2 c6 4 d4 e4 5 c4 8d6 6 Nc3 Ne7 7 g5 In his book Basman recommends instead 7 0b3 0-0 8 Bg5 16 9 cxd5 cxd5 10 Nxd5 Be6 11 Nxe7+ Qxe7 12 d5 but then 12 . . . Bf7 13 Be3 Na6 or 13 . . . Nd7 leaves White virtually lost since he will auto- matically lose the pawn on d5 and he cannot meanwhile develop his kingside. 7 . . . Be6 8 h4 Nf5 9 Bh3 Or 9 e3 Nxh4 19 Rxh4 Qxg5 winning. 9. . . 0-0 10 cxd5 cxd5 11 Nxd5 Or 11 Bxf5 Bxf5 12 Nxd5 Qa5+ 13 Nc3 Nc6 with a decisive lead in development. 11 . . . Ng3! (Diagram) Bas- man completely overlooked this. If 12 fxg3 Bxg3+ and 13 . . . Bxd5 or 12 Bxe6 Nxhl 13 Position after 11

. . Ng3!

Bh3 Bh2! stabbing White's knights in the back. The rest is a slaughter. 12 Nf6+ gxf6 13 fxg3 Bxg3+ 14 Kfl Nc6 15 Be3 Nb4 16 Kg2 Nd5 17 Kxg3 Nxe3 18 Qd2 Qd6+ 19 1(12 Qf4+ 20 Nf3 exf3 White resigns 21 Oxe3 Qh4+ is hopeless for White.

Players who could well benefit from a dip into Basman's unorthodox text are the young prodigies Gata Kamsky and the Polgar sisters. In all cases I fear that the excessive influence of over-ambitious fathers may have led to an excess of circus training and learning by rote which leaves the young hopefuls relatively helpless and lacking a creative identity when faced with unforeseen crisis situations in the practical struggle. Witness for example Zsuzsa Pol- gar's collapse when faced with a new move in the Seville Variation of the Grunfeld. In the game Karpov — Kasparov, Amster- dam 1988 Black had played 18 . . . Bh6. Wolff' s innovation threw Zsuzsa Polgar completely and after a few more moves as White in a well documented variation she was faced with a disastrous endgame.

Szusza Polgar — Patrick Wolff: San Francisco 1991; Grunfeld Defence.

1 d4 Nf6 2 c4 g6 3 Nc3 d5 4 cxd5 Nxd5 S e4 Nxc3 6 bxc3 Bg7 7 Bc4 c5 8 Ne2 Nc6 9 Be3 0-0 10 0-0 Bg4 11 13 Na5 12 Bxf7+ Rxf7 13 fxg4 Rxf1+ 14 Kill Qd6 15 e5 Qd5 16 Bf2 Rd8 17 Qc2 Qc4 18 Qb2 Rf8 19 Kg! Qd3 20 Ng3 Bh6 21 Qe2 Qxc3 22 Rdl cxd4 23 Bxd4 Qc4 24 Bxa7 Qxe2 25 Nxe2 Nc6 26 Bc5 Ra8 27 Nc3 Ra5 28 Bb6 Ra3 29 Nd5 Rxa2 30 Rd l Bg7 31 e6 Rd2 32 Nc7 Be5 33 Re4 Rdl + 34 Kf2 Rbl 35 Na8 Bx1t2 36 Bc7 Bgl + 37 Ke2 Rb2+ 38 Kfl Bd4 39 Bf4 Rf2+ 40 Kel Rxg2 41 Bh6 Rh2 42 Bg5 Ra2 43 Nc7 Ra5 44 Bh6 Be5 45 Bf4 Bxf4 46 Rxf4 Rc5 47 Kf2 Ne5 White resigns.

Even worse is the case of 16-year-old Gata Kamsky whose personality seems to have merged entirely with that of his father.

Gata Kamsky and his father Rustam were interviewed by the Indian Interna- tional Master Manuel Aaron shortly after Gata tied for first place with Anand at the Delhi tournament of December last year.

One of the answers constitutes perhaps the most extraordinary response I have ever seen in an interview on any subject. Gata was asked whether the views express- ed in the interview were those of himself or those of his father, and what came out was this strange composite statement. (By the way, all the talking in English is done by Gata who performs a remarkable simul- taneous translation as his father pontifi- cates in Russian) 'These are our views. I am only 16, so I can't have my own views. He is my son, my work, my love. He has given eight years of his life to me. He doesn't have a life for himself. Not every- body can do this, you know.'

The first sentence of the above could be a joint statement. The second sentence is obviously Gata, while the third sentence is equally obviously Rustam. The final three sentences are completely interchangeable, they could be the father referring to the son or vice versa or a combination of the two. This sort of thing is no good if one wants to play chess independently and well.

Previous page

Previous page