CITY DIARY

CHRISTOPHER FILDES

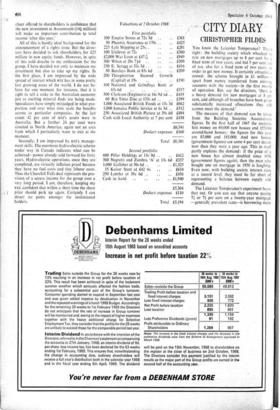

You know the Leicester Temperance? That's right : the building society which whacked its rate on new mortgages up to 8 per cent for a fixed term of two years, and bid 5 per cent net of tax, also for a fixed term of two years, in order to get new money. It certainly attracted a crowd : the scheme brought in £1 million—

apart from money transferred from existing accounts with the society—in the- first month of operation. But, say the directors, 'there is a heavy demand for new mortgages at 8 per cent, and although all branches have been given subitantially increased allocations they still 'cannot meet the demand.' ' The measure of that demand can be taken from the Building Societies Association's figures. In the first hall of 1967 the societies Even now, with building society interest rates at a record level, they must be far short of teptesenting a .balance between supply and demand. '

The Leicester Temperance's experiment bears that out. Or you can say that anyone paying 7-i or 7f per cent on a twenty-year mortgage —generally prevalent rates—is borrowing more £6,541 lent money on 69,000` new houses and 155,000

second-hand .houses: the figures for this year are 85,000 and 185,000. And new houses (goVernment figures) are some 4 per cent dearer now than they were a year ago. This in itself partly explains the demand: if the price of a new house has almost doubled since 1956 (government figures again), then the .man who bought one on mortgage in 1956 is laughing.

cheaply than the Government can. The redemp- tion yield of a government stock with twenty years to run is now 71- per cent. Or you can observe (the example comes from Money Which?) that if you are buying a car, rather than a house, on borrowed money, as a member of the Automobile Association you can borrow (by means of hire purchase) at 17 per cent— and this is advertised as a concession.

One of these IMF meetings, I suppose the delegates from Bongoland will make so splendid a speech as to carry his case by storm, and hardened central bankers will cry with one voice 'Yes! We agree! Forward intervention shall only be proportionate to automatic gold tranches!' But with the IMF, as with papal elec- tions—and it occurs to me that after that slash- ing attack from Mr McNamara they might at least make the Vatican a member—the way of direct inspiration is less common than the way of discreet horsetrading. It is the unreported speeches that count.

This time round, a fair amount of those speeches will come from or to the Germans. It suits everybody else's book to have the Deutschemark written up: whether it actually suits the Germans is something that they them- selves still find difficult to decide. The Bundesbank now seems to be warming to the idea. It has at least let the pros and cons be argued in its bulletin—imagine the Bank of England doing the same for devaluation in the Quarterly! Politically, though, it seems some- thing of a hot chestnut. The business com- munity doesn't care for it, and the unions have persuaded-themselves that its effect would be to put prices up. (What do they think devaluation does?) Next year is election year; so if the mark is to be revalued, it must therefore happen some- time in the 'seventies or within the next two or three months. No prizes for guess- ing which choice the Germans are being pressed to make.

I enjoy (you may remember) Mr Cecil King's contributions to public life. His latest, a paper on 'Industry and mass communications' for the Industrial Educational and Research Founda- tion, shows him in vigorous form : 'The news- paper in Britain as we know it today is usually produced in black and white, on expensive wood pulp, and in a manner which Caxton or Gutenburg could too quickly grasp.' One of our great national problems is education for management, and I can imagine no better general background of general business know- ledge for a young man than the one he can get by reading the business pages.' I say, I hope I can take that one personally.

'If the skilled workers in your plant conform to the national average' (says Mr King) 'then one in every two of them takes the Daily Mirror. If you yourself do not read that newspaper it might be, I may suggest, a useful exercise—it

will soon develop into a pleasure . . I call that magnanimous to the International Publish- ing Corporation. Redundancy is not a solution for a company like IPC (or so one of its direc- tors wrote in its management journal the other day): problems of that sort could be solved by the normal processes of attrition and early re- tirement. And which of these was applied to Mr King? Both, I suppose.

The triple-distilled and indefinably smoky flavour that you detect in my prose this week is the effect .of two instructive days in the distilleries of Dublin. As a professional assign-

ment this can only be compared with the post offered by Mr autterbuck to Captain Grimes, of going round the Clutterbuck pubs making sure that the beer was up to standard; and I can say that even the Captain's stamina would have been put to the test.

Time was when the sales of Irish whiskey and Scotch whisky were on much the same mark. But in 1939 the Irish government forbade the export of whiskey, having other sources of foreign exchange and needing the excise duty. The ban was not lifted until 1952; and the result is an industry which sells three quarters of its production to a home market of less than three million people—in contrast to the Scotch distillers, whose home market is almost more trouble than it's worth. Ireland is protected, but that ends in three years' time when Anglo- Irish free trade comes into force; so that the Irish distillers needed to strengthen their position without all that much time to do it in.

The three distilling companies, each dom- inated by a ruling family—the Crichtons at John Jameson, the O'Reillys at Power's, the Murphys at Cork—and separated even by

religious differences—(Jameson is proverbially the Protestant and Power the Catholic whiskey) boldly came together two years ago with a triple merger, and are now pleasingly known as UK for United Distillers of Ireland. This year Mr Kevin McCourt gave up the running of the Irish television service to become urn's first managing director: from this appointment an integrated management structure is following. But it is the sales sides which has seen the most concentration of effort, with the English market- ing effort in the hands of a new purpose-built company and the Irish sales forces amalgamated —as delicate an exercise, I should have thought, as merging Rangers and Celtic.

Whisky, as you know, is difficult to make and requires a heavy investment in maturing stocks: Power's has just abandoned its early nineteenth century millstones, but we shan't be able to tell whether this was right for another ten years. But—and this I didn't know—gin and vodka seem easy to make, and can be sold almost at once. Look out for amazing com- mercial developments in this diary : bargain gin offers to readers; see that the brand-name Bathtub is on every label.

Previous page

Previous page